FEATURES|COLUMNS|Creativity and Contemplation

Meditation as Sustenance for Death and Dying

Who is dragging this corpse around?

This huatou, similar to a koan, was popularized by Hsu Yun, a famous Chan Buddhist master of the late 19th/early 20th century. The riddle gets to the heart of the dichotomy of life and death. Vajrayana Buddhism describes us as living corpses; the saying goes that the leading cause of death is birth! Preparing for death, we consider three aspects: ordinary practical details (such as one’s estate), concerns related to the body, and the mind. For Buddhists, the last is most important, being the only facet of our human existence to go with us. Except, will we any longer be an “us,” the treasured “me” we presently think ourselves to be? This is what drove me repeatedly to tearful panic as a young child, to discover Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha in high school, and ultimately, to Vajrayana meditation practice. If mind creates everything and all is a reflection or refraction of mind, then what is there to worry about? In brief, the answer is “karma and forgetting”: two major problems. The antidote to ignorance of life’s true nature is awareness—being awake. As my teacher described it, “back mind watches front mind.” This witness lends space to perceive the illusory nature of all things, ourselves included.

Mirrors and maps

When we die, we slough off the shell of selfness—our body, personal history, and identity. What remains is the mind stream. The compassionate lineage masters provide us a clear road map to handle this new state, to both avoid treacherous pitfalls and recognize vital signposts. The key point is being prepared to navigate the bardo (between-state) after death rather than be blown about helplessly on the karmic winds. Not having studied the map, what use would it be to simply unfurl it at the moment of death? Imagine attempting extreme skiing for the very first time in the Olympics, with no prior experience! So we familiarize ourselves with the path, map, and symbols through meditation. Vajrayana Buddhism is thorough, compassionate, and grounded. The Great Liberation Through Hearing text has three sections to be spoken into the ear of the dying, to liberate beings of the highest, middle, and lowest capacities of awareness. The overall instructions for all three begin with:

Every experience in this world is Mara’s dream-like illusion.

Everything is impermanent, everyone is subject to death.

Noble one, turn away from further painful states.*

The text goes on to describe what the dying may likely perceive and gives specific guidance for each phase of the senses’ dissolution, tailored for one’s level of capacity.

Buddhism is brilliantly well researched, scientific in nature, and based on personal experimentation rather than on blind trust or fable. The Buddha admonished, “Do not accept what I teach just out of faith or respect for me, but investigate for yourself as if buying gold.”** The key is meditation, guided by a genuine teacher, wherein a seeker gains experience, proficiency, and confidence in letting go, over and over, practicing for death. In this way, life and death are two sides of a gold coin. Rather than being a cliché, this is very much a literal truth. “Death is a brilliant mirror that offers us discernment about life’s priorities and a deep appreciation of the power of mind.”*** For the dying process not to be painful and confusing, there must be preparation. We apply this common sense in most every area, and death must be approached as a natural occurrence, not eschewed as a distasteful taboo. Masters of meditation experience death’s transition as a mere change of clothes, and have described it as best they can, motivated by great compassion. Yet crossing over is a solo journey, one that we must each traverse alone.

Betweens

Grappling with the huatou enigma is intended to be carried out by laypeople immersed in ordinary activity. Contemplating death regularly, we celebrate and fully embody life while we still breathe. This cultivates presence, gratitude, and authentic connection with oneself, others, the natural world and all her creatures, be they spiders, birds, cows, or unseen beings. It is often remarked that advanced spiritual practitioners die professionally. What does this mean? It can entail remaining seated serenely in meditation posture with all worldly affairs settled, often on a day they pre-appoint, having left instructions for followers. Inwardly, one remains in equipoise without fear, distraction, or regret, but with deep knowing that only the “venue” has shifted; there is no drop into voidness. An ordinary person when dying seeks love, peace, reconciliation, forgiveness. The extraordinary seek to offer these qualities to all sentient beings. To leave this plane and to return to benefit beings is their sole purpose. Awakening to nirvana, enlightenment, or perfect peace is for all beings, since there is no distinct self to ultimately covet such attainment.

Laurie Anderson’s unique film Heart of a Dog expresses the permeability between life and death in an organic montage of sounds, images, animation, family video footage, and voice-over—an impressionistic view of the continual bardo overlap of living and dying. She deftly weaves past, present, and fantasy future into a quirky patchwork quilt, threaded through with humor and music (indeed, where would we be as a species without humor and music?) We need only gaze at the natural world to see the continual birthing and dying of all things—all the more poignant in this era of climate change and uncertainty. Seen partially from a dog’s-eye view, the film has no linear sense of time but blends memories and perceptions in watery dreamscape. Equal emphasis is given to humans, animals, weather, sounds, scenery, and emotion, all appearing in overlay, similar to the description of the experience of bardo beings.

Grief

Life abounds with endings besides the deaths of loved ones and familiars. We experience the slow or sudden decay of our health and faculties, friends and lovers move on to other relationships, loss of opportunities and dissolution of all kinds abound. Grief itself is a fertile journey. It is something that happens to us, and like the infliction and healing of a physical wound, has its own process and timeline, quite beyond our control. As a creative journey, we forge a new relationship with that which is lost, develop modes of coping, and re-create ourselves in the process. Our capacity to grieve is as deep as our power to savor life. We relish, cherish, and treasure life’s joy and connection just as we shun, dread, and repress grief. But the only way out is through, and those who have experienced terrible losses know this to be true. Deep grief tattoos our heart-mind, yet it’s an earned mark, enabling us to be a resource for others as well as for our own death transition. The intense poignancy of impermanence challenges us to savor life’s beauty and goodness while we can, and to offer to those less fortunate in any way possible.

Feeling the keen sorrow of loss, it is imperative to express it outwardly, to prevent anguish from turning inward as depression or disease. Keening, a vocal tradition in Ireland and Scotland, had women wailing at funerals in praise and lament of the dead, releasing the intensity of bereavement and uniting mourners. Similarly, a close friend of mine described the intense vocalizations she needed to sound in order to withstand the pains of naturally home-birthing her child. Activation of this primal expression of pain and praise is a deep human instinct for midwifing both birth and death. We literally call beings into or out of this earthly realm. Our soulful voice is the bridge between body and heart-mind.

Self-care and expression

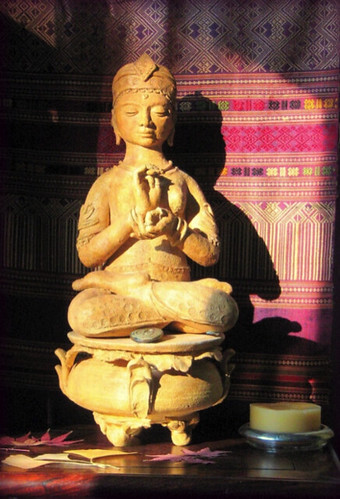

In modulating the intensity of life’s joys and sorrows, there are many ways to express our full range of experience. There are myriad modes of engaging in self-care reflection, whether to complement meditation, to aid the dying, or to nourish ourselves as caregivers. Yoga, breathing, laughter, qigong, and calming techniques for anxiety are all activities to care for our multifaceted human nature. The arts, including painting, sculpting, movement and dance, drama, drumming, music, and writing provide outlet for emotion, inspiration, and sensation, which are so in need of meaningful expression. Gardening, bodywork, herbal remedies, and immersion in water are invaluable supports. An acupuncturist once gave me a potent qigong exercise to perform nightly at bedtime to relieve the anxiety and panic associated with grief and uncertainty. Sitting on the edge of the bed, one imagines that one’s lower legs and feet are immersed in a gently flowing river. Invoking the sound, feel, and movement of the water, one allows all worries to flow away with the current. By massaging oil or lotion into the lower legs and feet, tension and apprehension flow down and out and are released to invite restful sleep. I have often found this technique to be soothing, as is playing an audio recording of soft ocean waves.

Offering and praise

Meditation enriches our experience of life and helps guide both us and others through the natural process of dying. If it’s new territory, Pema Chödrön’s books are an excellent starting point with their clear and earthy style. Caring for ourselves and others through expressive means is an act of great compassion, honoring and acknowledging the fullness of our human complexity and intuitive wisdom. In the 2008 Japanese film Departures, the main character Daigo takes the job of nokanshi, or traditional Japanese ritual mortician, who sends off the dead by preparing the body with utmost care and respect. The ritual itself is a meditation on death and an offering for loved ones left behind. In this tradition, death is neither abhorred not glorified, but simply honored as a natural passage:

“He brings dignity and beauty to these intimate moments. Every gesture in the ritual washing, dressing, grooming, and putting on of make-up is performed with the kind of presence and attention we would associate with the Japanese tea ceremony. Not a movement is wasted in this art which moves slowly and demonstrates that touch is the most exquisite of our senses.”****

In hatha yoga, each session ends with shavasana, the corpse pose, which harmonizes and releases all the postures which have come before. Once it has been completed, the yogin turns onto the right side in fetal position, and then rises up again to sit in meditation posture, to bow in praise. A perfect microcosm of the cycle of life-death-rebirth. May we have the grace to accept the fleeting nature of all experience, and to fully savor the gift of this precious human life through meditation, offering, and full creative expression.

* Padmasambhava, The Bardo Tödrol (The Great Liberation Through Hearing). http://levekunst.com/how-to-die-a-teaching-from-the-lotus-born

** http://www.berzinarchives.com/web/archives/sutra

*** http://www.brownpapertickets.com/event/2504565, used with permission by Chagdud Khadro, personal communication 15 March 2016

**** http://www.spiritualityandpractice.com/films/reviews/view/19092/departures

See more

Moondrop Meditation (workshops with Sarah C. Beasley)

A Vajrayana practitioner since 2000, Sarah C. Beasley (Sera Kunzang Lhamo) spent over six years in retreat under the guidance of Lama Tharchin Rinpoche and Thinley Norbu Rinpoche, engaging in the traditional Vajrayana path of experiential cultivation. In 2013, Sarah worked closely with Lama Tharchin Rinpoche and his wife on compiling and editing the text Vajrasattva Ceremony for the Dead to make it available for seasoned and beginning practitioners alike. She is encouraged by Lama Yeshe Wangmo to offer practical instruction based on this compilation text. Sarah is an experienced teacher, writer, sculptor, dancer, and Iyengar yoga practitioner. She will be leading a workshop, “Meditation for Death & Dying,” at Kauai Hospice from 25–27 March, including an expressive arts self-care component for caregivers. For more information, email seraklhamo@yahoo.com. See also On dogs, hopelessness and pure vision.