FEATURES|THEMES|People and Personalities

“Mind the Gap Between Appearance and Reality”—Barry Kerzin Offers a More Nuanced View of Happiness

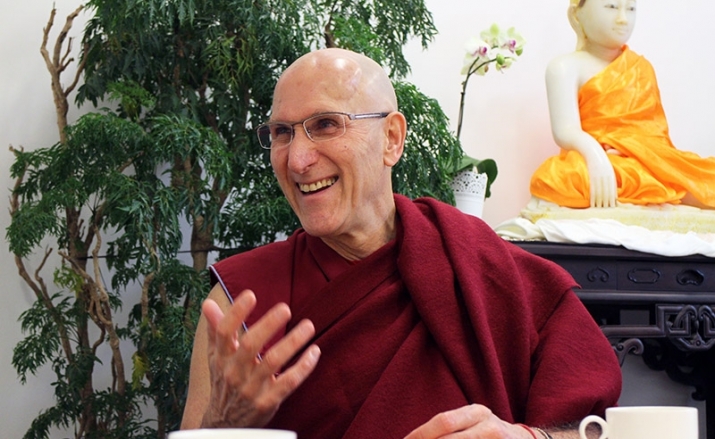

Barry Kerzin. Photo by Buddhistdoor

Barry Kerzin. Photo by BuddhistdoorBarry Kerzin is a very busy monk with such a demanding schedule that we were lucky to even have time to meet. He is currently teaching at Hong Kong University, while also managing the Altruism In Medicine Institute (AIMI) non-profit organization, which he founded in 2014. In April he heads to the University of Oxford to speak at the Saïd Business School and participate in the Skoll World Forum (13–15 April), before flying to Tokyo to teach a Lojong* course at St. Luke’s International Hospital in May. Then he will be at the Grand Rounds at Stanford University School of Medicine in July, where some of the world’s top healthcare professionals share their discoveries and their obstacles in the field of medical research. Finally, he is scheduled to visit Pittsburgh in October to speak to about 600 doctors on his current research, and I’m sure his Christmas schedule must be just as demanding.

A doctor by training and a former assistant professor of Medicine at the University of Washington in Seattle, Barry, originally from the US, has been immersed in the interdisciplinary world of healthcare and Buddhism since the mid-1980s. As a Buddhist he has become a household name among Western practitioners, the community in Dharamsala, where he spends much of his time as a personal physician to His Holiness the Dalai Lama, and global Vajrayana circles. I believe his remarkably busy but productive diary is evidence that partnerships between medicine and Buddhism are becoming embedded in the healthcare field.

Coincidentally, my conversation with him took place shortly before International Happiness Day on 20 March. It is troubling that we need an international day to raise awareness about happiness, and ironic that we dedicate only one day in the year to a question that countless people have asked for millennia—“How can I be happy?” Buddhism’s answer to this question has been consistent throughout its long history: happiness is not what we think it is and, rather than being the outcome of any particular endeavor, attaining happiness stems from a profound understanding of the nature of reality.

“Happiness is often understood as pleasure arising from the senses,” says Barry. “Take touch, for example: we derive pleasure from physical contact with our loved ones. Or taste: we feel pleasure from a delicious ice cream scoop [his favorite is black sesame]. None of this pleasure is bad, but we must accept that it is limited because it must end by its very nature.”

The cruel irony, he points out, is that the never-ending pleasure many of us fantasize about would quickly become a nightmare. Barry illustrates his point with the example of eating at a sumptuous buffet where a friend continually urges you to refill your plate to the point that your stomach feels bloated and indigestion takes over. “Sunbathing is also a good example—it’s well known that there are serious repercussions with overexposure to the sun, like skin cancer.”

Barry then moves on to the problematic question of love. Doesn’t love provide happiness? “Yes, but strings are always attached,” he says, “even for relationships where we dream of unconditional love, such as between spouses or between parents and kids. It is really hard for a relationship to even exist if a couple doesn’t commit to loving each other, and a parent, no matter how much they do for their child, often still feels unhappy if that child doesn’t give affection or gratitude in return.”

If there is a “secret” or “key” to happiness, Barry argues, it is not to be found in the external senses or perceptions. Happiness lies deep in our consciousness, where one moves beyond conceptions and reaches a non-conceptual, non-dual state of mind. “I use non-duality in terms of subject and object,” he says. It certainly takes time to live habitually with a realization of non-duality in a dualistic world of subjects and objects, but Barry proposes several methods that help us move toward that state. The first critical step is cultivating a sense of altruism and compassion for others.

“Think about this. At the end of the day, we are all the same in wanting happiness. None of us wants to hurt; none of us wants to suffer. This is what His Holiness the Dalai Lama and so many others have said many times. We always need to remind ourselves of this fundamental common ground. It is more basic than any of our differences, even if the differences seem greater. Essentially, we’ve got to punch through the superficial,” he explains. “We must relate to this truth at the deeper level, repeating it to ourselves like a mantra. The more we want to help others and act on that altruism because we know deeply that others don’t want to suffer, the more we can feel this stable, lasting happiness growing within us.”

This kind of happiness is not an intense feeling because it is not a reaction to something outside of us. Instead, it is a profound sense of contentment that grows as we act on our concern for others. “Compassion and altruism are the main avenue to developing a truly ‘default’ state of inner and lasting happiness that is deeper and subtler. It leads to bodhichitta, the awakened mind. Of course, wisdom is the other side of this equation because it is what we need to understand emptiness, shunyata,” says Barry.

“Shunyata is really the deepest reality of things. Shunyata means that reality is characterized by impermanence, that everything is made up of parts, and that far from being independent, everything is dependent: all things are subject to dependent origination. Together, compassion and wisdom lead us to happiness.” But shunyata also means that every single phenomenon in our world can only occur through an incredibly complex web of interconnected events. Barry and I were drinking tea at the time, and he held up his cup by way of example, showing the interconnectedness of all the people who would have been involved in its manufacture and eventual delivery into his hand at the HKU campus.

“How wonderful that the tea in this cup also is the result of farmers growing these plants far away, the drivers of the vehicles transporting these leaves all the way to Hong Kong, and so many other people and things that have made even this meeting between you and me, along with the tea in this teacup, possible,” he declares. “We are so dependent on each other for so many things.”

Beyond altruism, compassion, and wisdom, Buddhism’s path to happiness lies in readjusting our understanding of reality. Insight is the most important attainment in Buddhism, and Barry concludes with a very relatable image. “I love the signs on the London Tube that say, ‘Mind the Gap.’ They’re talking about the gap between the train and the platform, but I like to use it in a different context, which is to mind the gap between appearance and reality,” he laughs.

“Our ego is our worst enemy. It deflates or inflates the world as it is—making things not what they are—which in turn distorts our perceptions and engages our destructive emotions like anger, greed, and delusion. When we begin to recognize all this we are better equipped to stop it ever engaging in such activities. When we see through all the forms and illusions and really perceive reality, we become at ease, happy.”

* Lojong is a series of mind training practices based on the aphorisms of Kadampa master Chekawa Yeshe Dorje.

See more