FEATURES|THEMES|People and Personalities

Monk in Modernity: Bhante Sanathavihari

This article was originally published by Buddhistdoor en Español. The following is a translation of that article.

Our daily lives have been abruptly affected by unprecedented change as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the final consequences of which we cannot yet understand. In this context, cyberspace and social media offer us a virtual environment in which to meet up, learn, dialogue, and perhaps reflect on our modern-day culture and the need to find other ways of thinking and living.

Bhante Sanathavihari Bhikkhu is a Mexican-American Theravada monk who lives in the Sarathchandra Meditation Center in North Hollywood, Los Angeles. He represents a new generation of Spanish-speaking monastics who are extensively employing digital communication methods and social media, which is turning out to be extremely effective for spreading the Dharma in Spanish.

Bhante Sanathavihari Bhikkhu, whose birth name is Ricardo Ortega, is 35 years old. He was born in Los Angeles and received a Catholic education. He has a BA in religion from the American Military University and spent nine years in the US Army. After three deployments to Afghanistan, he was ordained as a novice in the Theravada tradition, at the age of 30, in the lineage of the Amarapura Nikaya monastic fraternity. In 2015, he received higher ordination at the Sarathchandra Buddhist Center of the Maharagama Bhikkhu Training Center (Maharagama Dharmayathanaya) in Colombo, Sri Lanka. Today, Bhante Sanathavihari is the leader of Casa de Bhavana, a Theravada organization devoted to spreading the Dharma and promoting the practice of meditation

In this interview, Bhante Sanathavihari Bhikkhu talks with us about his background and his inspiration and vocation of sharing the Dharma online in Spanish.

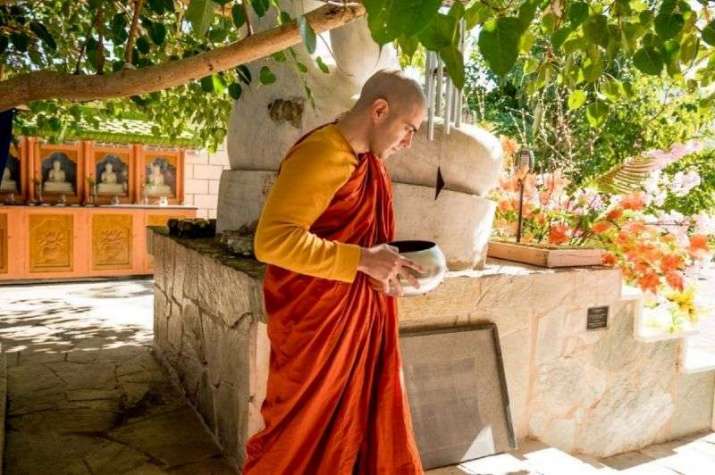

Bhante Sanathavihari Bhikkhu. Image courtesy of Casa de Bhavana

Bhante Sanathavihari Bhikkhu. Image courtesy of Casa de BhavanaBuddhistdoor en Español: Bhante, we’d love to hear a little about your background. Could you tell us how you decided to become a monk?

Bhante Sanathavihari Bhikkhu: My decision to become a monk occurred a couple years after I started studying Buddhism. One day, at my local Theravada monastery—which I found via Google—I went to my regular meditation class on Friday night. However, one of the monks told me there wouldn’t be meditation that evening and that, instead, an older visiting monk was going to give a Dharma talk. His presentation didn’t do much for me, but the next talk by the monk—my future master Bhante Madawela Punnaji—was a catalyst for re-evaluating what I really wanted in my life. At that time, I had embarked on a journey toward self-realization and was becoming the person I believed I wanted to be. It was the typical narrative of young men who want to look good, be in good physical shape, have a nice car, a beautiful girlfriend, and so forth. However, after I obtained what I thought I wanted, I didn’t find the satisfaction I was seeking. That was the fuel for the spark of Bhante Punnaji’s talk about the Dharma. After that, I decided to live it as much as possible in my life. The Dharma became my priority to see if I could satisfy this existential restlessness and concern that constantly troubled me.

Bhante Madawela Punnaji. Image courtesy of Casa de Bhavana

Bhante Madawela Punnaji. Image courtesy of Casa de BhavanaAt that time, I was ordered to do another tour of duty in Afghanistan with the US Air Force. However, I kept up my daily Dharma practice, which consisted of reading the Dhammapada, chanting, meditating, and watching online talks about the Dharma. When I returned from Afghanistan, I did a couple of meditation retreats and, during one of them I knew that my future was to become ordained. Although most of my friends thought I was at the summit of my life, I was no longer satisfied with mundane life.

BDE: After your long stays in Afghanistan and your immersion in the Buddhist teachings, what led you to dedicate your life to spreading the Dharma in Spanish?

BSB: To tell the truth, I had no intention whatsoever of sharing the Dharma in Spanish. I didn’t even have the intention to share the Dharma in English. However, there was a pre-existing Latino community at the monastery where I was ordained and still live—the Sarathchandra Buddhist Center—and I found that I was continuously explaining the Dharma to them in Spanish. And one day they encouraged me to start a YouTube channel called “Monk in Modernity.”

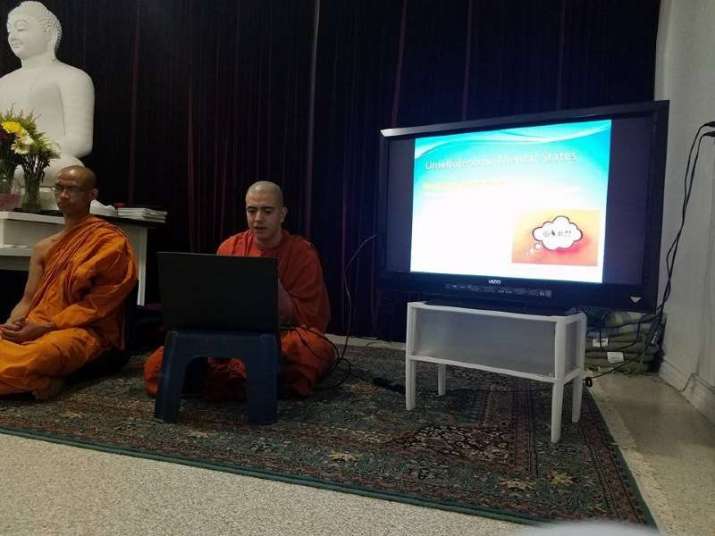

Image courtesy of Casa de Bhavana

Image courtesy of Casa de BhavanaBDE: It seems clear that you are devoted to an admirable task of sharing the Dharma. Which communication media do you use to disseminate the teachings?

BSB: As I mentioned earlier, my work started on YouTube, until the day that a man from Barcelona, Spain, invited me to start a Facebook group that would be centered on sharing the Dharma in Spanish. It has been about three years since we started that group, which is called Casa de Bhavana. The group has done online live group meditations. We started off using Skype and, for the last two yearsnwe have been using Zoom. We also have a website, casadebhavana.com.

BDE: What aspects of the Dharma do you dedicate the most time to during your teachings?

BSB: My focus has always been practice, an informed practice based on the Pali suttas and the Vinaya. I conduct Dharma talks with a twofold perspective, one of which is early Buddhism and the other the psychological view. Most of the content on our Facebook group and YouTube channel refer to the Pali suttas or are meditations.

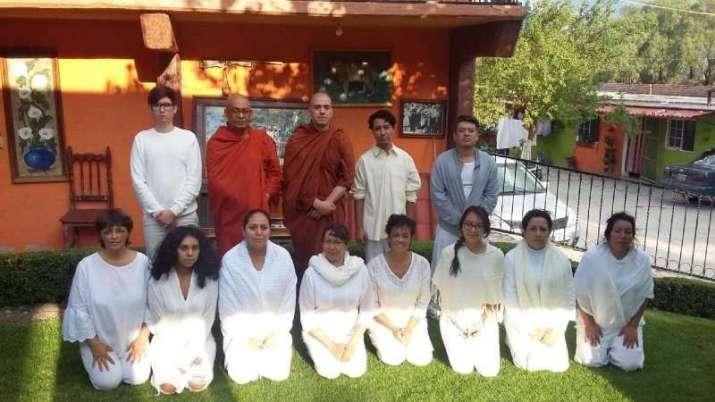

Image courtesy of Casa de Bhavana

Image courtesy of Casa de BhavanaBDE: Who is your audience? From which Latin American countries do you see the most followers and which countries do you visit to spread the Dharma?

BSB: According to analytics from YouTube, Facebook, and Amazon, the majority of our followers are from Mexico and, in second place, from Spain. These results have increased even more due to the fact that we have been conducting meditation retreats both in Mexico and Spain. We published a translation into Spanish of Bhante Punnaji’s book Return to Tranquility in Spain. Our community at the Sarathchantra Buddhist Center is made up of Mexicans, Guatemalans, Peruvians, Salvadorians, and many other Latin American communities.

BDE: What tips could Buddhism give us today about the consequences of COVID-19? How should Buddhists handle the pandemic?

BSB: I don’t think I can say anything new about the situation with the pandemic. The virus is like all the other tragedies in the world. Every year in the United States, around 88,000 people die in alcohol-related incidents. How many people die of hunger every year? We are always surrounded by death, everywhere. The pandamic is just a highly publicized tragedy. What Buddhism can do is remove the bandage from our eyes so that everyone sees the instability, the insecurity, the impermanent and unsatisfactory nature of existence. I would like to share some teachings now by my deceased master Bhante Punnaji:

Everything close and beloved by me is subject to change and separation. When these things change and leave, the only thing left is an emotional state (kamma). My emotional state makes me unhappy. Depending on external and changing conditions for my happiness, I experience sadness and unhappiness. As long as I do not depend on these external conditions for my happiness, I cultivate detachment, compassion, happiness and tranquility and gain true happiness. Pleasure is stimulation of the senses. Happiness is a mental state free from egocentric emotions.

Everything is dependent on conditions.

Because it is dependent on conditions, it is unstable.

Because it is unstable, it is uncomfortable.

Because it is uncomfortable, it is not under my control.

Because it is not under my control, it is not mine.

Because it is not mine, it is not my “self,” nor a part of me.

Ariyamagga Bhavana Level I

Image courtesy of Casa de Bhavana

Image courtesy of Casa de BhavanaBDE: Could you tell us about your future plans?

BSB: My future plans are to found monasteries in Mexico and Spain. I would also love to found a Spanish-speaking Buddhist center in Los Angeles. I know, I’m very ambitious, right? However, I have always been a dreamer. I see a great thirst for the Dharma in the Spanish-speaking world. I think that the Dharma was only accessible to the rich in Spanish-speaking countries for a very long time, and my dream would be to bring the Dharma to everyone for free and without any religious conversion. I hope I can help people who have little or no access to resources—the people who are most vulnerable in our society. And one more thing I would like is to see Latinos ordained in their countries of origin. When the king of Sri Lanka asked Bhante Mahinda if the Dharma had been established in Sri Lanka, he said no, until there were Sri Lankan bhikkhus, we could not say that the Dharma had been established in Sri Lanka. So, as long as there are not bhikkhus ordained in Latin America, we cannot say that the Dharma has been established in Latin America.

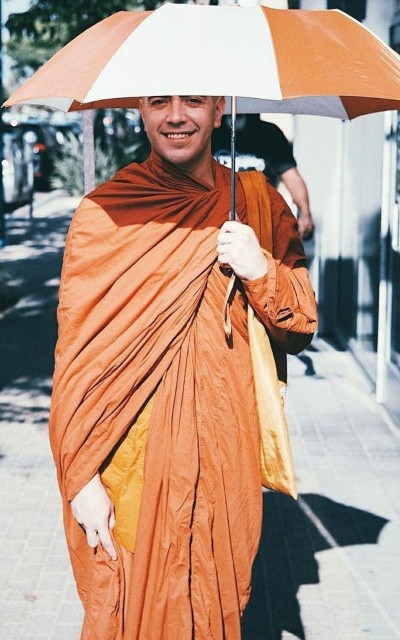

Bhante Sanathavihari Bhikkhu.

Image courtesy of Casa de Bhavana

See more:

Casa de Bhavana

mettasutta y metta bhavana (benevolencia) (YouTube)

Meditación con Centro Arya: Yoga & Psicologia (YouTube)

Segundo Sermon del Retiro en Mexico 2018 (YouTube)

Anicca Bhavana (meditación de impermanencia) (YouTube)

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Integrating Dharma Practice in Spanish: An Interview with Venerable Dhammadīpa Samaneri

A Life of Dharma: Fernando Tola and Carmen Dragonetti

Interview with Montse Castellà Olivé, President of Sakyadhita Spain

Zu Lai Temple: The Largest Buddhist Temple in South America

Interview with Abraham Vélez de Cea About the Buddha’s Outlook Toward Other Religious Traditions

Dharma in Translation: Lhundup Damchö