FEATURES|COLUMNS|Buddhist Art

Mudra: Understanding the Buddha’s Hands

Buddhistdoor Global | 2015-01-23 |

Detail of the Buddha Amitabha with hands in the meditation gesture, Kotoku-in, Kamakura, Japan. 13th century, bronze. Photograph by Meher McArthur.

The hand gestures, or mudra, assumed by figures of the Buddha and other deities are some of the most fascinating aspects of Buddhist iconography. Similar to the graceful hand gestures used by performers of traditional Indian dance, mudra are often the key to identifying deities portrayed in Buddhist sculptures and paintings. Frequently, they illustrate an important aspect of the deity’s own story or the particular way in which he or she can help devotees realize their own enlightenment. There are many different mudra, some specific to particular deities and particular moments in their evolution, others used widely by Buddhas, bodhisattvas, and deities ranked lower in the hierarchic Buddhist pantheon. Those formed by the various manifestations of the Buddha are particularly revealing about aspects of the Buddha’s life and achievements and the powers he and his manifestations are believed to possess.

Buddha making the gesture of fearlessness, Lingyin Temple, Hangzhou, China. 10th century, stone; Photograph by Meher McArthur.

Probably the most commonly used mudra in imagery of both the Northern and Southern traditions of Buddhism is the abhaya, or “fearlessness,” mudra. Made only by Buddhas (fully enlightened beings) and bodhisattvas (beings who have postponed their own imminent enlightenment in order to help others), the gesture represents the benevolence of and absence of fear in the deity because of his or her advanced spiritual power. It is made with the right hand raised to shoulder height, the arm bent and the palm facing outward. According to Buddhist legend, when the historical Buddha Shakyamuni was being attacked by an angry elephant, he simply held up his hand and calmed the raging beast. However, since a hand free of weapons is universally regarded as a sign of friendship and peace, the mudra also confers the absence of fear on others.

Seated Buddhas making the earth-touching gesture, Ayudhaya, Thailand. 15th century, stone. Photograph by Alan McArthur.

The Earth-touching mudra, bhumisparsha mudra, is one of the most significant gestures since it represents the moment when Shakyamuni attained enlightenment and became the “Buddha,” or the “Enlightened One.” According to tradition, while Shakyamuni was meditating under a tree, the evil king Mara sent beautiful women and armies of wicked demons to distract him from his goal of enlightenment. However, the Buddha was not stirred from his intense meditation, and reached down with his right hand to touch the ground beneath him, taking the Earth as the witness of his resolve. It was at this moment that he attained enlightenment. Paintings and sculptures of the Buddha touching the Earth are particularly common in the Southern Buddhist traditions practiced primarily in Thailand, Cambodia, and Sri Lanka, where the life and teachings of the historical Buddha are of more importance than the powers of other deities.

The Buddha Amitabha with hands in the meditation gesture, Kotoku-in, Kamakura, Japan. 13th century, bronze. Photograph by Meher McArthur.

In the Northern traditions of Buddhism, comprising the Mahayana schools of East Asia and the Vajrayana tradition of the Himalayas and Japan, devotees believe in more than just one Buddha. In these traditions, there are several Buddhas representing various aspects of his powers and teachings, many bodhisattvas and other deities, and so too a wider range of mudras. One of the principal Buddhas in these traditions is the Buddha of Infinite Light, Amitabha, who is believed to reside in the Western Paradise and will reward his followers with rebirth there. In many representations, Amitabha is shown with his hands in the dhyana, or meditation, gesture, with both hands in his lap at the level of his belly. The right hand rests on the left with palms facing upwards, the fingers extended and the tips of the thumbs touching to form a slightly flattened triangle, representing the Three Jewels of Buddhism—the Buddha, his teachings, and the religious community. A variant of this mudra can be seen in a famous bronze statue of the Great Buddha at the temple Kotoku-in in Kamakura. Here, the Buddha’s forefingers bend to touch the thumbs, symbolizing the highest level of rebirth his followers can attain in his paradise, a level at which they are better positioned to receive Amitabha’s help towards enlightenment. This variant and two others (in which the two middle fingers or the two ring fingers touch the thumbs) are also used by Amitabha devotees, representing higher, middle, and lower levels of rebirth, respectively.

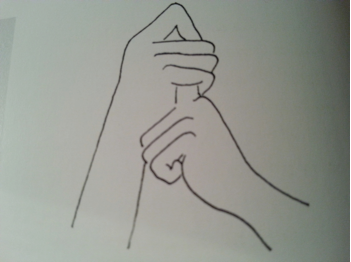

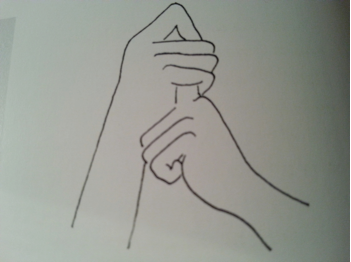

One of the most intriguing mudras is that used in the esoteric imagery of Japan, China, and Korea, and occasionally in Tibet. Known as the “Mudra of the Six Elements” or the “fist of wisdom,” it is specific to the Cosmic Buddha, Vairochana, and is made by enclosing the erect forefinger of the left hand in the right fist with the right forefinger covering the tip of the left. The five fingers of the right hand are said to represent the five elements of the universe: earth, water, air, fire, and ether, protecting the sixth element, which can stand for either man or the Buddha mind. The erect forefinger can also be said to represent knowledge, which is hidden by the world of appearances and illusion. The mudra additionally has strong sexual symbolism, embodying the union of the male and female forces of the universe. It is most often seen in Japanese esoteric imagery and is the mudra equivalent of the Himalayan yab-yum images of male and female deities in sexual embrace.

Drawing of the “fist of wisdom” mudra by Carol Porter. From Meher McArthur, Reading Buddhist Art: An Illustrated Guide to Buddhist Signs and Symbols, London: Thames & Hudson, 2002, p. 116, fig. 1.

While some of the above-mentioned mudra are formed by bodhisattvas and other Buddhist deities, typically, these deities are identifiable by the objects they hold rather than their hand gestures. Since images of the Buddha hold the greatest spiritual power of all Buddhist figures, an understanding of their symbolism and gestures is critical not only to followers of the religion, but also to art lovers who wish to better read and understand its complex imagery.

Meher McArthur is an Asian art curator, writer, and educator based in Los Angeles. She has curated over 20 exhibitions on aspects of Asian art. Her publications include Reading Buddhist Art: An Illustrated Guide to Buddhist Signs and Symbols (Thames & Hudson, 2002), The Arts of Asia: Materials, Techniques, Styles (Thames & Hudson, 2005), and Confucius: A Biography (Quercus, London, 2010; Pegasus Books, New York, 2011).

See more photographs by Alan McArthur at Chiang Mai: A Day of Photography.

Comments:

Share your thoughts: