In this series, Jnan explores the practice of ordination within the Theravada tradition by a close examination of the Pali Canon. His first article discusses ordination during the Buddha’s lifetime.

The Pali term pabbajja, denoting ordination, comes from the prefix pa and the root vaja (to go forth). It occurs in various sections of the Vinaya and Sutta Pitaka. The frequency within the Pali Canon of the use of the phrase ‘agarasma anagariyam pabbajati’, or similar phrases recording the action of going forth from home to homelessness, is a common feature in the ancient Indian civilization. For example, in the Cakkavattisihana-sutta, the Wheel Rolling Monarch renounces the worldly kingdom to take up celibacy and the spiritual life. Furthermore, several Jataka stories, which depict the previous lives of Gautama Buddha, also contain events surrounding renunciation.

The concept of ordination or renunciation is a pre-Buddhist ideal. The Vedic texts divide up the life of an individual into four stages, with celibacy as the last stage. The six heretical teachers, also contemporaries of the Buddha, were people who had renounced the worldly life. Sukumar Dutt, in Early Buddhist Monachism, mentions wanderers who have renounced the worldly life, designated by titles such as, pravrajaka, bhikkhu, samana, yati, sannyasin etc. Their objective in seeking renunciation was the search for highest truth (sacca) and highest virtue (kusala). However, the Buddha, also a renunciate of the worldly life, was different from those wanderers and ascetics.

According to the Susima-sutta of Samyutta Nikaya, the Buddhist practices were advanced. Susima, a wanderer, takes ordination in the Buddhist Order under the misperception that spiritual life in Buddhism is the attainment of various supernormal powers. However, the Buddha and some Arahants later explain to him that this was not so. The meaning of spiritual life in Buddhism is living in accordance with the Dhamma that leads to the attainment of Nibbana. At this stage, the bhikkhu realizes the five aggregates are impermanent and through the understanding of Dependent Co-origination, a bhikkhu attains Nibbana declaring ‘birth is ended, the spiritual life is lived, done what has to be done and there is nothing more left to be fulfilled in the life.'

In the Bhikkhaka-sutta of Samyutta Nikaya, the Buddha explains that one does not become a bhikkhu by merely begging for food and wandering with unwholesomeness. According to the Buddha, a bhikkhu is one who has given up merit as a sin in this world and observes celibacy with a pure mind. A bhikkhu is one who does not acquire merit (punya), but does wholesome activities (kusalakamma). Punya is for lay followers, kusala is for the monastic who is striving on the path to nibbana.

The Mahatanhakkhaya-sutta of Majjhima Nikaya explains the nature of a bhikkhu as a bird that flies with only its wings: a bhikkhu is happy with robes for the use of the body, food for the use of hunger, as a bird uses its wings wherever it flies. These statements in various sutta-s show that the Buddha has given a very different and standard definition of bhikkhu in Buddhism.

The Buddhist concept of ordination was formulated in a practical way and is a natural step towards emancipation. Buddhist teachings are more practical than metaphysical as in other religions. The Buddhist practice, once taken up, ultimately leads to liberation.

According to the Oghatarana-sutta of the Samyutta Nikaya, the Buddha crossed the flood of samsara by neither pushing forward nor staying in one place (flood/stream). The Buddha explains that if he stayed, he could have drowned and, if he struggled too much, he could have lost his achievement. So, without staying and bothering, he crossed the flood (stream). This shows the middle way characteristic of the Buddhist path of practice free from being extreme. The Buddha without being an extremist crossed the stream smoothly; he neither stayed in the middle of the stream nor rushed to cross the stream. He crossed the stream while following the middle way.

Such a meaningful life attracted a vast number of people to lead a spiritual life under the guidance of the Buddha. In the beginning, when the size of the Sangha was smaller, the Buddha himself granted ordination. However, as the Dhamma continued to spread, more people aspired to be ordained but were unable to do so. It was difficult to meet the Buddha, as he was the only one with authority to grant ordination yet journeying from one place to another preaching the doctrine. At this stage the Buddha decided to permit his disciples to ordain people who were willing to enter the Order.

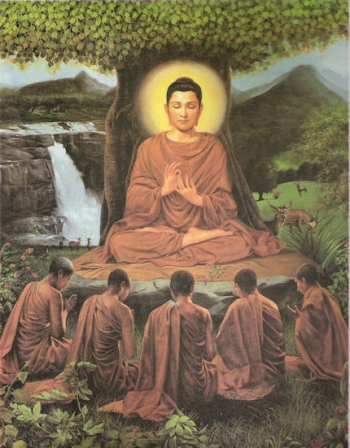

The authority of granting ordination up until the Buddha finally gave permission to other monks to do so, had remained fully with him. The ordination granted by the Buddha at that time was called ‘ehi bhikkhu pabbajja’, which means ‘O monk, come and take ordination’, an invitation extended to those who had expressed a willingness to enter the Order. The first person to receive this ordination was Kondanna, the first to understand the Buddha’s first sermon among the first five disciples. Secondly, the remaining four disciples requested the Buddha for ordination and were granted ordination in the same way. When the number of candidates was more than one, the Buddha used the plural form: etha bhikkhavo’ti. According to both the Vinaya and its commentaries, there were thousands of monks who received the ehi bhikkhu pabbajja, taking the Buddha as their preceptor.

The type of ordination granted by the disciples (with the permission of the Buddha) to ordain new entrants to the sangha was called the tisarana pabbajja. This means taking ordination by uttering the Triple Gems three times separately. The tisarana form of ordination was instituted after the Buddha decentralized the authority of granting ordination. Furthermore, there was no distinction between samanera (novitiate) ordination or upasampada (higher ordination) during Buddha’s lifetime. In both formulas, ehi bhikkhu pabbajja and tisarana pabbajja, the monks were automatically admitted to full ordination at the same time when the ordination was granted. The most important purpose for entering the Order at that time was neither seniority nor being junior, but to practice spirituality to end dukkha and its root causes.

Part II of this series will discuss ‘Samanera (Novice) and Temporary Ordination’.

Further Reading

Dutt, S. (1996). Early Buddhist Monachism. Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers.

Horner, I.B. (Trans.) (1971). The Book of the Discipline. London: Luzac and Company Ltd.

Wijayaratna, M. (1990). Buddhist Monastic Life. C. Grangier and S. Collins (Trans.) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.