FEATURES|COLUMNS|Ancient Dances

Performative Iconography, Part One

This write-up is based on a presentation given by the author at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London in October 2018, during the symposium “Historical Perspectives on the Culture and Practices of Tantric Buddhism.” The topic is Performative Iconography. The audience was a select panel of world specialists in tantric Buddhist religion and art, convened in preparation for a groundbreaking exhibition on tantra opening in 2022, under the direction of John Clarke and Ian Baker, and touring worldwide.

Local boys in the village of Thangbi, Bhutan, demonstrate the apparently well known “dakini dance.” 2007. Photo by Gerard Houghton for Core of Culture

Local boys in the village of Thangbi, Bhutan, demonstrate the apparently well known “dakini dance.” 2007. Photo by Gerard Houghton for Core of CultureLet’s begin with Bhutanese schoolboys showing us “dakini dance.” Each day that we went to do research on the murals in the temple in Ngangbi, Bhutan, they would appear before us dancing. They couldn’t figure what the big deal was. Everybody knew how dakinis danced.

Performative iconography is a term coined in the art criticism of the 1960s to discuss conceptual art. It is a creative use of the words and has proven useful in evolving discussions of art. Today, the term is being applied to Buddhist archaeology, anthropology, cultural preservation, and as an expansion on the meaning of Buddhist art, reflecting both a greater understanding of the embodied physicality of Buddhism, as well as a sophistication of critical discussion around Buddhist transmission from person to person.

Here are some ways to get at it:

Performative art has “a reality-producing dimension”

Performative art “implies methodological orientation”

Performative art has a “prescriptive code beyond surface description”

Tibetan bronzes, animal-headed wrathful deities with weapons. From Core of Culture

Tibetan bronzes, animal-headed wrathful deities with weapons. From Core of CultureThese three Tibetan bronzes are not posing in order to be identified. They are roaring forward, pushing off their back feet, in a striking martial advance. It is iconography in frozen motion. In reference to a Buddhist thangka painting, for example, the term performative iconography is straightforward: you are not supposed to look at a thangka; you are supposed to do a thangka. It is an instruction, a symbolic code for how to conduct tantric meditation. The main purpose of the thangka is not what it looks like, but what state of mind it generates. Thangkas are performative art; art intended to be performed.

Wrathful Herukas dancing in Thangbi, Bhutan. 2006. Photo by Gerard Houghton for Core of Culture

Wrathful Herukas dancing in Thangbi, Bhutan. 2006. Photo by Gerard Houghton for Core of CultureThese bucolic farmers dancing Buddhist cham come roaring forward in wrathful demonstration. It is not just that the dance is wild, it as much that the icons of wrathful deities are the dancers. The word, “icon,” has different meanings depending on specialized use. Byzantine Christian art, pop art, and internet culture have made claims on the word. Andy Warhol produced icons. His Electric Chair is considered an icon. He made a cow icon also, famously turned into wallpaper. That was once further developed together with the Electric Chair into an immersive environment in which the observer/participant found themselves and had choices to make regarding how to experience it, both mentally and physically: thus, performative iconography. Icon implies a symbolic system.

Cow wallpaper with Electric Chair. 1966. Andy Warhol.

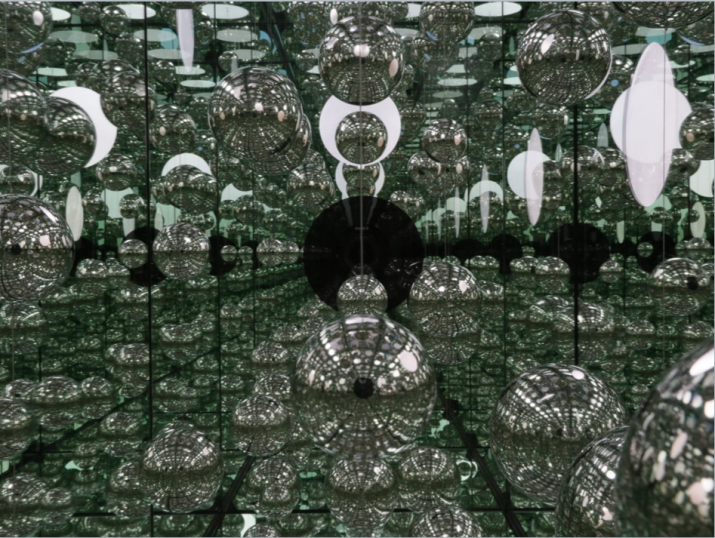

Cow wallpaper with Electric Chair. 1966. Andy Warhol.Contemporary artist Yayoi Kusama, who lives voluntarily in a psychiatric hospital, produces art in great waves of thematic and iconic magnitude. Her Infinity Mirror Room series is composed of variations on the theme of her endless mind, a mind that the observer/participant stands in, and in which they move around, so . . . in whose mind are you standing? Where is in, in forever? These Infinity Mirror Rooms have been described as performative iconography. You don’t go to look at them, you go to experience them, and your experience is the real art. What Kusama’s “crazy mind” actually put forward is a literal performance of her mind. There is something dimension-shattering and ego-shattering in her work.

Infinity Mirror Room. 2018. Yayoi Kusama

Infinity Mirror Room. 2018. Yayoi KusamaThe term “performative iconography” is meant to create a different perspective on what produces meaning in art, beyond formal analysis. What kind of situation does the artwork produce? How does the work of art situate the viewer? The focus is on the experience and being of the viewer, rather than that of the artist. It marks a transition from the aesthetics of the object to the aesthetics of experience. Art re-aligns one to one’s own experience. This is how tantric art works.

While the term is slippery and sometimes broad, it is obviously useful in discussing art with more vitality. Aspects of the discussion of contemporary art give insight into Tantric Buddhism’s fundamental and prevalent use of performative iconography. What follows are a number of examples of performed and performative iconography not only in Tantric Buddhism but in other archaic Asian cultural systems. Some of these are well known, but perhaps their genuine performative character can be emphasized today.

Daoyin Tu diagram of energetic exercises from Mawangdui Tomb. 206 BCE. China. From Core of Culture

Daoyin Tu diagram of energetic exercises from Mawangdui Tomb. 206 BCE. China. From Core of CultureThis example is the famous Daoyin Tu chart of “guiding and pulling exercises,” excavated from a tomb site at Mawangdui, China, older than 200 BCE. Clearly these depicted exercises—still performed today—are meant to instruct in their performance. The art’s purpose relies on the reality that the exercises are intended to be performed, not merely observed as depictions. This scroll was part of a wealthy man’s burial treasures.

With regard to Tantric Buddhism, the words are used plainly: performative means, “intended to be performed” or “being performed.” Iconography means a Buddhist religious icon as per the canon of standard Buddhist iconography. What follow are basic examples of tantric Buddhist techniques in which embodied icons are activated. This is often done using dance, both in the physical and ephemeral realms. Meditation visualizations dance too.

Paintings depict dance, sculptures freeze dance. Paleolithic cave paintings appear to dance when the flames of fires and torches illuminate them. Why is dance, and embodied movement practice, the animating technique of Buddhist deities, and how does dance further animate them with performative intent, involving the viewer? Dance actual, dance depicted, and dance ephemeral, such as in meditation visions, together create the shared vital arena of performed iconography.

Mahasiddas. Mural painting, Tamzhing Monastery, Bumthang, Bhutan. 2005. Photo by Gerard Houghton for Core of Culture

Mahasiddas. Mural painting, Tamzhing Monastery, Bumthang, Bhutan. 2005. Photo by Gerard Houghton for Core of CultureDance is an iconographic identifier. These mahasiddhas are from Tamzhing Monastery in Bhutan. The mahasiddhas, early tantric masters, are known for their extreme physical contortions and mastery of yogic shapes. This canonic artistic treatment of the mahasiddhas in mid-movement indicates not only who they are, but what movements animated their embodied practice. Dance does more than identify, both in art and in actual dancing. As a rule, the dances and movement traditions depicted in Buddhist art are real and existed before being depicted.

Dance brings order. Dance divides space. Dance brings rhythm to geometry. Dance is made of life. Dance can alter consciousness. Dance can conduct and cultivate energy. Dance expresses divinity. Dance sustains states of mind. Dance adorns form. Dance adorns phase transition. Dance gives movement to shape.

Monastic cham dance is not merely for external observation. It is a yoga—a spiritual technique—for monks. Cham moves from stillness to empowered chant called mantra, then to empowered hand gestures called mudra, and on to the movement, the "deity action” of cham; a progression from vibration, to form, to pattern. There is a method by which the icon is performed.

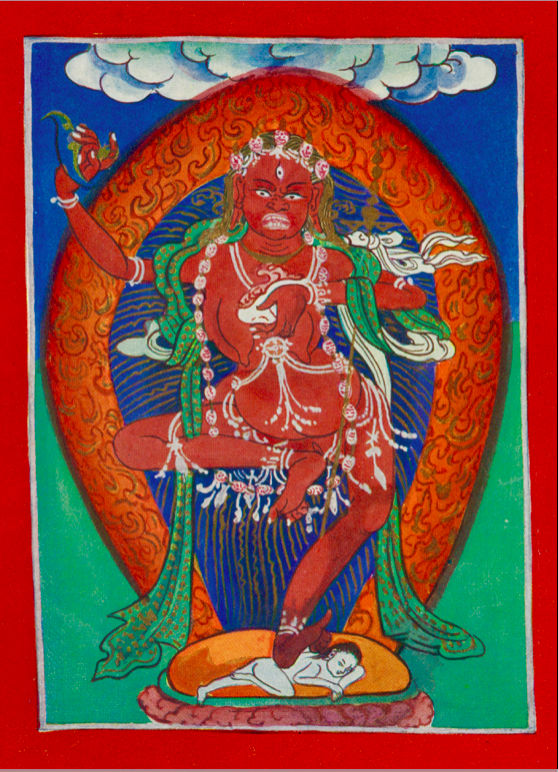

Vajrayogini. Thanka painting, 19th century, Bhutan. From Core of Culture

This is a beautiful Bhutanese thangka of Vajrayogini surrounded by yoginis, deities, and masters of meditation. This thangka can be performed variously in meditation as it contains multiple instructions in its shapes, characters, and colors. It provides a course in iconographic devotion, having eight yoginis circling the central deity in a counter-clockwise dance. Four two-toned yoginis circle in a different, clockwise dance. The thangka provides a course in the lived experience of protecting the directions, and it provides a course in the exploration of dimensions of the mind.

This requires skill at animating dancing visions. This tantric vision has choreography: simultaneously moving, different choreography, in different directions. This is an advanced meditation technique, spiral upon spiral. Dance, moving through the figures, colors, and signifiers, progresses through mystical space. It is the process by which the thangka is animated in the mind and its protective virtues generated in the meditator. The icon is performed as a yogic visualization, not as a physical dance.

Atsumori, a Noh play. 2009. Noh actor Mikata Shizuka. Victoria and Albert Museum. Photo by Jonathan Greet for Core of Culture

Atsumori, a Noh play. 2009. Noh actor Mikata Shizuka. Victoria and Albert Museum. Photo by Jonathan Greet for Core of CultureA Japanese Noh actor also transforms his consciousness through movement, by using energy and mental skills to convey the spiritual condition of famous historical figures, producing a Zen-like awareness of the beauty, sadness, and transience of life. Noh is a trance-like drama, an art form, designed for spectators. In both cases, tantric meditation and the Noh theater, enacting the art forms is the vehicle for spiritual and energetic transmutation.

Protector of the Vajrakaya. Tsaparang Monastery.

Published by Tucci in Indo-Tibetica. 1935. TAV. III.

This amazing figure of deities dancing in erotic embrace is from Tsparang Monastery, photographed during an expedition led by Giuseppe Tucci in 1933. Tucci was fascinated by the dancing figures of deities in erotic embrace and was the first to notice that the deities were in fact dancing. In this clear example of performed iconography, the male deity’s weight is on one foot only, the other foot turned outward. Here the dance controls the icons from wantonness, providing structure, rhythm, and context, and fashions them into symbols of subsumed transcendence. This is an image of the mastery of human nature. Tantric Buddhist practice does not deny natural powers. It transforms them into something Buddhist, with natural powers enlivening the practice of embodied deities.

Vajrayogini, published in Evans-Wentz, Tibetan Yogas and Secret Doctrines,

painted by Tendup La. 1958. Oxford University Press.

In an edition of the Six Yogas of Naropa, a book considered to be a “boot camp” for tantric meditation, we find this compelling illustration of Vajrayogini. The first yoga, tummo (Tib. inner heat), in this core book of Vajrayana meditation includes this figure of Vajrayogini slicing the air with a curved blade. She appears, a naked, ferocious, 16-year-old female. This is lesson one in beginner’s meditation. It begs the question what does the meditator actually conjure in their visualization when instructed to have the deity Vajrayogini dance and attain this position?

Vajrayogini’s movement is not a static pose, it is a highly charged martial strike created by spiraling the arm so that the curved blade cuts outward. She strides in an advancing step to further empower the spiraling strike. In other versions, she cuts off her own head. It is a ferocious act of martial behavior, not merely a symbol for an intellectual idea. Enacted in the meditating mind as a martial act, the visualized icon becomes further animated, more lifelike, changing the quality of the meditation and opening access to integrated powers.

Also in the tummo meditation instructions is a layered technique of performed iconography connected to the breath.

1. Perform Deep slow breaths.

2. Continue to breathe, in and out through every pore in the body. Stabilize this breathing.

3. Imagine mantric syllables pouring through every pore with each breath cycle.

4. Make these syllables various colors, such as correspond to Buddhist elements. Stabilize this breathing as multi-colored syllables are coursing in and out of the entire body with every breath cycle.

5. Transform these colored syllables into wrathful deities of various colors. Every pore becomes a colored wrathful deity; with each breath in and out, the wrathful deities dance.

The meditator becomes a living, breathing mandala of wrathful deities, covered in protective amour. In fact, it is good to point out that wrathful deities always dance. It is what they do. These first basic instructions for tantric meditation practice are exercises in performed iconography, rather elaborate, and joined with breathing techniques. Performative iconography is the materia prima of tantric meditation.

Coming next month: Performance Iconography, Part Two

See more

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Performative Iconography, Part Two

Monklife, Part One

Monklife, Part Two: An Obstacle Clearing Ritual

Monklife, Part Three: Mantra, Mudra, Movement, Mask – Steps to Embodiment