FEATURES|COLUMNS|Ancient Dances

Power and Beauty: Robert Wilson Takes On the Last Dynasty

Shattering expectations is what many exhibition curators claim to do. At the Minneapolis Institute of Art (MIA), curator of Chinese art Liu Yang has produced an exhibition of rare Qing dynasty (1644–1912) objects from MIA’s extraordinary collection, in collaboration with avant-garde theater director Robert Wilson. The sense of high style and design, floor to ceiling, like a Pina Bausch set, put total and lofty focus on the objects, construed inversely by the operatic scale of this theater of the mind. The objects were the focus, put into a lucid dream drama of the cultural mind considering a lost empire, adorned with the rare and precious art of the splendid Qing dynasty.

Pina Bausch, Tanztheater Wuppertal, World Cities (Saitama), London, 2012. An immersive, visually stunning set design. Image courtesy of the New York Times

Pina Bausch, Tanztheater Wuppertal, World Cities (Saitama), London, 2012. An immersive, visually stunning set design. Image courtesy of the New York TimesWilson is famous for directing the watershed Einstein on the Beach, with music by Philip Glass and choreography by Lucinda Childs. It presented a highly symbolic, non-linear, patterned series of music, movements, and visual ideas. It was opera, so opera had clearly become something entirely new. Glass was always influenced by Eastern ideas and music and has written scores for Japanese- and Tibetan-themed films, dealing with spirituality and art. To call Power and Beauty operatic is fair—it speaks in bold stokes and huge metaphors—the kind that can sweep you away, where an object is a lightening rod for memory and emotion.

The erudite and cheerful Liu Yang expressed nothing but admiration and professional pride in working with the famous Wilson. They were united in appreciation of these extraordinary objects, rich in symbolic as well as artistic value. Wilson himself is a collector of Chinese art and it is by this connection that Yang and Wilson met. To call the whole exhibition “theatrical” is almost inevitable. The lingering effect of an object isolated in space; a space where clearly the destiny of ages has played out, is indeed like that feeling at the end of a tragic ballet, where the reality plays out in lucid dreams that carry on. Where is the life of the object?

Buddhism has had its share of Hollywood treatment, virtual reality, augmented reality, holograms, but nothing quite like the old school power of five sculptural ruins in a room entirely covered in stainless steel. The two men, Yang and Wilson, wanted order to unleash spontaneity. In room after room, the visitor was aesthetically ambushed. Astonishment. Shock almost, that immediately turned all spectacle into sublime focus on the objects; the exquisite objects. My memory is better for having these objects linger within it.

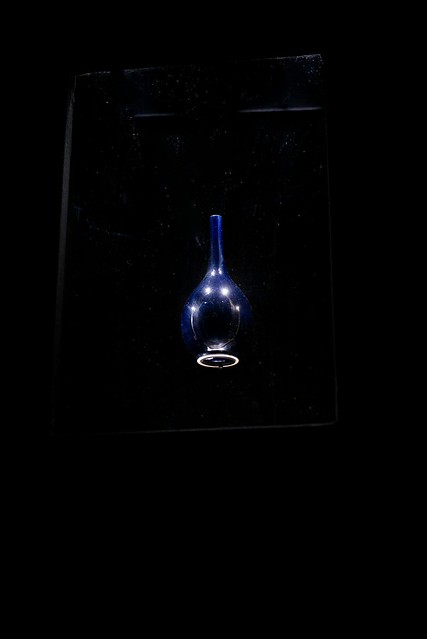

Qing dynasty bottle vase, porcelain, 19th century.

From the gallery named Darkness.

Image courtesy Minneapolis Institute of Art

Drama? Within the eight temporary galleries used for the show, four galleries contained only one object. To begin, a group of about 10 visitors is ushered into an entirely blacked-out room. The doors close. We sit for five minutes in the darkness. Piano music is barely heard. A single black vase in a searing light sits high in the opposite wall. One object: black on black, a great empire’s exaltation of the artistic object. The generative idea of the object. Shape. Perfection.

And Ka-pow! The opposite doors open to a dazzling white room, a white-frame exhibit structure appearing, with the object multiplied 200 times. Each object more perfectly made than the other. The Qing dynasty valued collecting ancient bronzes and art, and at the same time valued the fine production of all the arts.

The gallery named Prosperity. Installation view, Power and Beauty. Image courtesy of the Minneapolis Institute of Art

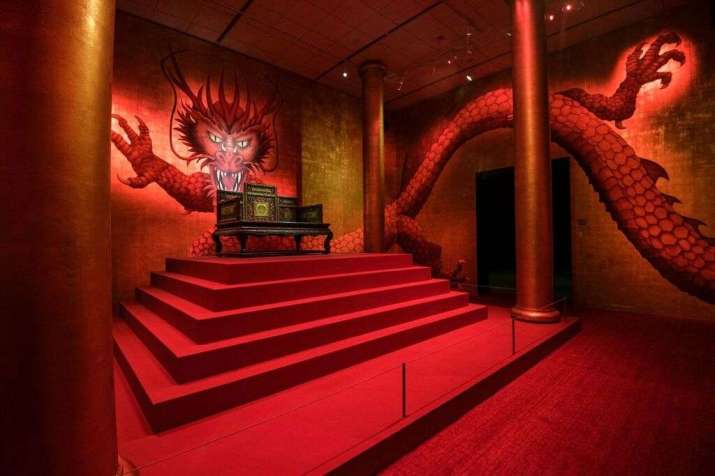

The gallery named Prosperity. Installation view, Power and Beauty. Image courtesy of the Minneapolis Institute of ArtOne gallery, Fearsome Authority, held only a single object. It featured the sole imperial Qing throne outside of the Forbidden City. It is a splendid example of the depth and excellence of MIA’s Chinese collection. Wilson provided the throne a mural of a dragon encircling the entire gallery, along with beautiful music that is punctuated with shrieking people being beheaded and attacked. Opposite the throne, in another gallery featuring only one object, is a fine, small, whole bronze of the Common Man from the Warring States period. (475–221 BCE). The contrast could not be greater, the objects no more sublime. The implications are immortal. Something to ponder, not something to read up on. It was breathtaking and high-flying. Part of the grandeur of the whole enterprise is seeing the Common Man so valued in 2018, so honored, such a constant. It is worth visiting the show simply to pay respect to this ancestor. The man who became the measure.

The only Qianlong imperial throne outside of China. 18th century. Featured solo in the Fearsome Authority room. Image courtesy of Minneapolis Institute of Art

The only Qianlong imperial throne outside of China. 18th century. Featured solo in the Fearsome Authority room. Image courtesy of Minneapolis Institute of Art Standing Figure, Warring States period ( 5th-4th century BCE ). Bronze with gold inlay, in the room named The Common Man. Image courtesy of Minneapolis Institute of Art

Standing Figure, Warring States period ( 5th-4th century BCE ). Bronze with gold inlay, in the room named The Common Man. Image courtesy of Minneapolis Institute of Art

Standing Figure, Warring States period ( 5th–4th century BCE).

Bronze with gold inlay (detail).

Image courtesy of Minneapolis Institute of Art

To be sure, the very high quality of art and objects on display made the theatrical magic of the exhibition glow with authentic splendor. The high-minded collaboration between Yang and Wilson distilled the impact of Buddhism and Daoism on the flowering of the Qing dynasty. These are vast topics for which scholars have never ended their explorations. Yang and Wilson have leapt over the squabble. The gallery named Buddhist Art to the left of the throne room was entirely made of stainless steel: floor, walls, and ceiling. Irregularly positioned, five Buddhist stone sculptures stood in streams and pools of dazzling white light. Each sculpture is broken and its remnant is shown, glamorous survivors all. It becomes an exquisite meditation on the long influence of Buddhism in Chinese history.

Experience rather than explanation was the choice. Robert Wilson made these comments at a Q&A around the opening: “In order to see this work, we need to empty our heads. Get the daily life and activities out of our minds so we can focus on something else. John Cage had a great influence on my thinking. He was one of the Western people that brought us closer to Eastern ideas. After having read Cage’s book on silence, my life was forever changed.”

Dvarapala, a Buddhist guardian figure, 8th century, stone (foreground). Back, from left to right, are Buddhist figures from the 6th, 7th, and 8th centuries. Impressive in their broken form, these pieces highlight the importance given to collecting and cultural stewardship. They are at the same time, an image of the cultural memory of Buddhism. Image courtesy of the Minneapolis Institute of Art

Dvarapala, a Buddhist guardian figure, 8th century, stone (foreground). Back, from left to right, are Buddhist figures from the 6th, 7th, and 8th centuries. Impressive in their broken form, these pieces highlight the importance given to collecting and cultural stewardship. They are at the same time, an image of the cultural memory of Buddhism. Image courtesy of the Minneapolis Institute of ArtThe gallery to the right of the throne room was named Daoist Art—a cave-like setting, earthy and raw, a half-light of emergent organic wisdom. Three large paintings of the highest imperial quality, rare to see anywhere outside of China, are portraits of Daoism’s Three Purities, exquisitely detailed and refined. The indigenous beliefs of ancient times find expression as state-sanctioned religion depicted with the finest artistry. The meeting of primal power and courtly sophistication attained synthesis in this magical installation; timeless and intimate.

The Three Purities. Ming Dynasty, late 16th century. Taoist paintings, pigment, ink and gold on silk. Image courtesy Minneapolis Institute of Art

The Three Purities. Ming Dynasty, late 16th century. Taoist paintings, pigment, ink and gold on silk. Image courtesy Minneapolis Institute of ArtAllie Mickle, of MIA’s Chinese department, offered these thoughts: “Power and Beauty showcases a variety of media represented in the museum’s Chinese collections, built over the years through both museum purchases and generous donations. Chinese art has been an important part of the collecting history of the museum, and with leadership from trustees such as Alfred Pillsbury, Augustus Searle, and Ruth and Bruce Dayton, the museum has had the advantage of connoisseur collectors with first rank knowledge of the market and objects. Over time, MIA has cultivated a distinguished collection of Chinese art with notable strengths in the areas of ancient bronze ritual vessels, jade, ceramics, sculpture, textiles, and the decorative arts.

“The works on display were created or collected during the Qing period. The objects and art works are relevant to each themed gallery but also speak to the larger contexts of imperial power and creativity through exhibiting the strength of the court’s sponsorship and patronage of the arts.”

Sankai Juku Butoh troupe in Umusuna, 2015.

What was once elemental theatricality became glamorous and chic.

Not bad. Not elemental. Something was lost in the sheen

Chic can be a liability in the arts, and Wilson is no stranger to charges of superficiality and squandering performing talent in the name of arty lighting. The “fully sensory” is an evolving concept. It can be as removed as Disney’s Imagineering, where the imaginary flight itself takes precedent. Spectacle and blockbuster approaches can hurt, even ruin, the viewing of an art show, as well as the complex understandings of art.

The power of raw and elemental Japanese dance, butoh, suffered when one prominent group moved to Paris and made it all quite fashionable and glamorous. Robert Wilson came of age as a lighting designer/director during this same period as the Sankai Juku dance troupe, and the searing oblique lighting that characterizes much avant-garde theater of the mid-to-late 1980s. Wilson developed this “look” more than others. It is a signature. It is a gorgeousness.

Undeniably gorgeous, this Power and Beauty, is not stretched beyond purpose, and never loses grounding in the art, which has no labels. That’s right, objects rarely seen from one of the finest collections outside of China—and no labels. It was a great idea for this show. Wilson has had many collaborators over the decades. This show was his first with a Chinese art curator. It has had a refining effect.

The absence of labels creates an immediately self-referential experience for the visitor. Just as in a performance audience: the reaction of the visitor matters to the climate of immersion and appreciation; all that matters, really. These objects are presented to ponder; to contemplate, to remember, to be worth remembering. That is the most traditional aspect underpinning the entire enterprise: the primacy of contemplating objects. The exhibition design focuses on the objects entirely, but it is all about the audience.

No labels? Where are we, the Documenta art fair, where last year the head curator infuriated the art world by not labeling the entries, site-specific works, and installations? This was very much a case of emperor’s new clothes in the field of contemporary art. If someone, or some label, doesn’t tell visitors what it is, or what it means, they are unable to make any sense of it at all.

Yet the effect is quite different when Qing dynasty artifacts and works of art are displayed in hyperbolic visual settings without labels, as here in Power and Beauty. They have a cultural power already. Fundamentally, lost civilizations live in the imagination in any case, specialist or philistine. Narrative upon narrative reveals itself: Qianlong Minnesota. What will hang there like a glamorous dream, bloom like a flower of the night never to be forgotten? This exhibition gives the world just that, again and again.

It is not a technology show, even though there is a lot of high technology in it. It is an art exhibition. In producing the show, it is remarkable that this superlative collection became the material prima for collaborative outdoor workshops between Robert Wilson and Liu Yang’s team at Wilson’s legendary Watermill estate on Long Island in August, 2017. Enormous tents were raised and projects from all over the world were setting up their own collaborative frameworks for Wilson to arrive to, and do his magic, al fresco. He is rather wizard-like.

Yang noted that part of the project was to lay out the gallery spaces exactly to measurement using wooden sticks in an open field, where the MIA team and other students posed as “objects” in each “gallery” so that Wilson could visualize each gallery spatially and envision the number and impact of works. Yang’s team included Matthew Welch, chief curator; Michael Lapthorn, exhibition designer; and Jennifer Komar Olivarez, head of exhibition planning and strategy. The museum director’s support is the prime mover in undertaking such an innovative approach with the museum’s top assets. Kaywin Feldman, MIA president, was behind Yang’s vision to bring on Robert Wilson. The entire project is a testimony to the skills and finesse at MIA.

This quickly-put-together exhibition, regrettably not traveling to other venues, opens the door to a much more radical re-focus on great works of art, civilization-defining works, in our era of re-definitions. Liu Yang is a perfectly placed man of vision as China’s stature in the world grows. He can teach the West and the East. It is important not to lose sight of the great themes, the grand concepts, the vaunted narratives of human accomplishment. Vaunting is what we do.

The Five Hundred Lohans, Qing dynasty, Qianlong period, 1736–95. Silk brocade with pigments. Image courtesy Minneapolis Institute of Art

The Five Hundred Lohans, Qing dynasty, Qianlong period, 1736–95. Silk brocade with pigments. Image courtesy Minneapolis Institute of ArtSee more

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

A Journey Through 5,000 Years of Tibetan History and Culture at the Capital Museum in Beijing

Manifesting the Higher Self: The Mandalas of Burton Kopelow

An Eye, a Lens, a Dance