FEATURES|COLUMNS|Ancient Dances

Rarified, Recondite, and Abstruse: Zeami’s Nine Stages

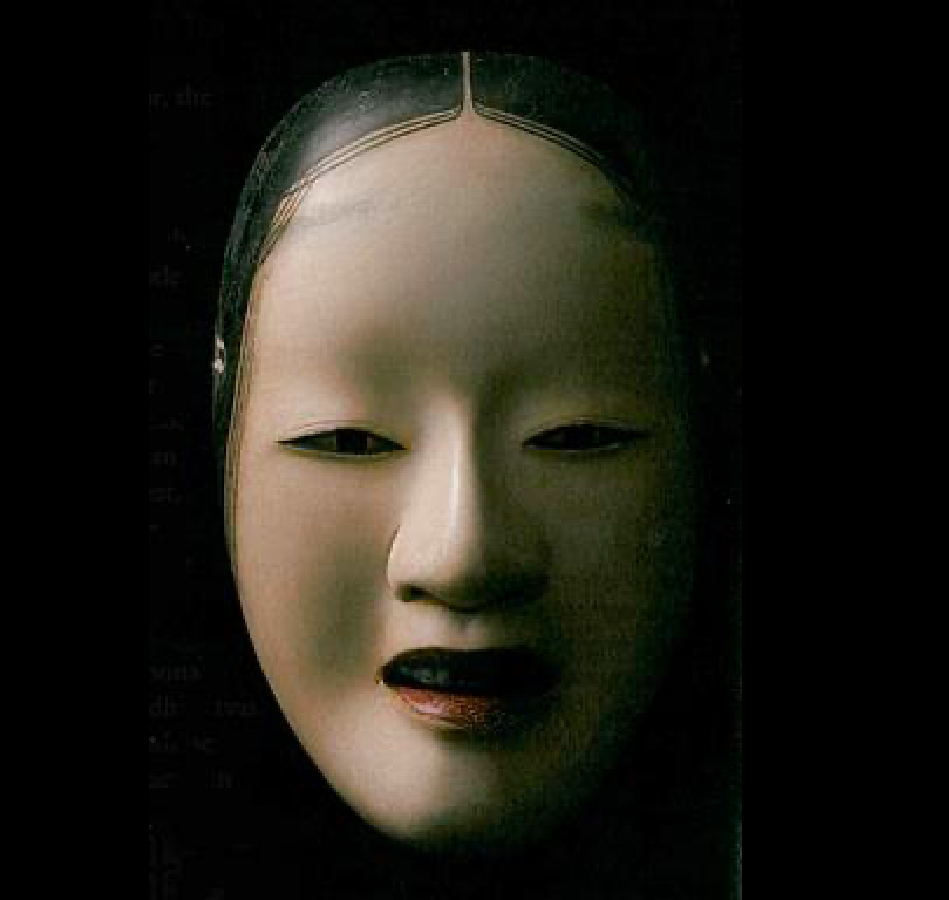

Noh mask, Zo Onna, 19th century. Sculptor unknown. Zo Onna signifies a beautiful,

slightly older woman who has experienced tragedy and gained wisdom. It expresses

a more composed and elegant figure than a younger woman. From Core of Culture.

If you ever have the chance to see a real Japanese Noh performance, seize the day. Noh is among mankind’s greatest artistic achievements. The metaphysical and practical aspects of Buddhism transform the art of Noh into something immediate and spiritual. But it is art, not religion. Zeami (c.1363 – c.1443), the 14th century founder, playwright, and theorist of Noh, made sure of this as he transformed street theater ghost-possession tales into an elaborate, minimalist, multi-art theater form.

Trance artists possessed by the ghosts of historical figures were replaced with actors depicting legendary historical characters as spirit beings who cannot escape the Wheel of Life and Death, and so cannot attain enlightenment. It has been said of Noh that characters do not enter and exit, rather they appear and disappear. The slow sliding walk of Noh creates another world. Most Noh plays are about these characters returning, pleading from another dimension, asking for prayers, to escape the Wheel of Life and Death, and in the meantime retelling their most famous fight, or love affair, or most beautiful memory, or sweetest revenge—attachments which still hold them in spiritual limbo and anguish.

Noh play Isutsu. The main character was betrayed in love. Here she peers into a well

where, as children, she and her lover would see each other. Now she is half-mad,

wearing his clothes, and when she peers in the well, what does she see?

Actor and photographer unknown. From Core of Culture.

Zeami specifically distinguished this style of acting as a “trance-like state”—that is, not a trance. A genuine trance was problematic for artistic reasons. If the actor really did enter a trance, then the artistic structure was not functioning as composed because the trance performer was unpredictable. If the trance was phony, then the core of the acting was false, and it was a bit of a performance con job, rather than a purely artistic product. Zeami saw that an uplifted acting would produce a higher level of artistry. What was spooky and entertaining became spiritually tragic and enthralling.

Zeami was discovered performing at a shine in Kyoto at the age of 11 by the Muromachi-era shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu (r. 1368–94), himself only 17. Against all court protocol, Yoshimitsu took Zeami, then a lowly actor boy called Fujiwaka, “Young Wisteria,” to his side, and introduced him into the artistic and religious milieu of the Muromachi epoch, one of the most creative and beautiful in all of Japanese culture. What began as a sexual relationship continued as patronage and became an intimate friendship that would span their entire lives.

Yoshimitsu’s eye in selecting Fujiwaka, and generosity in educating him, was inspired and changed the course of world theater, Japanese aesthetics, and performance theory. Fundamentally, Yoshimitsu was a warrior, a victorious general, and knew the transience of life firsthand in battle. This union of the erudite martial shogun and the young artistic prodigy gave the world Noh, one of the lasting cultural accomplishments of the Muromachi era, 600 years ago. Their integration of Buddhist thought into the deepest levels of cultural expression remains a rarely matched standard.

Zen Buddhism proliferated during the rule of Yoshimitsu. Zen Buddhist monks attained prominent positions in Yoshimitsu’s government, with him establishing the defining characteristics of their age: success in war, cultural beauty, and Zen Buddhism among them. Many Zen temples and Buddhist palaces were built during Yoshimitsu’s reign, the most striking of which is the shining Golden Pavilion, a Zen monastery called Kinkaku-ji, that was Yoshimitsu’s final home, after taking the tonsure as a monk. Noh and Kinkaku-ji, even today, reveal the depth of cultural accomplishment of Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu.

Woodblock print by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839–92). Ashikaga Yoshimitsu

at Kinkaku-ji, a Zen temple known as the Golden Pavilion. From wikimedia.org

Fujiwaka was trained in poetry and the classical literature of China and Japan. He studied Buddhist philosophy, Zen meditation, calligraphy, and aesthetics, surrounded by the brightest minds, the highest Buddhist teachers, the greatest poets, and the most accomplished artists. He learned the etiquette of the court and the artistic temperament of the shogun. Fujiwaka, contemplative by nature and an actor by birth, was religious in his behavior, and used Buddhist principles of conduct and aesthetics as his guiding rule.

Acting was his path during a period when gei-do, or “the way of aesthetics,” was paramount. A disciplined and devout Buddhist, Zeami wrote: “The essence of art is to unite high and low, and bring joy to the hearts of the people.” Zeami is a posthumous religious name, combining Kanze, his family name, and the Buddhist phrase Amidha Butsu (Amitabha Buddha). His actual name was Kanze Motokiyo. Ze-ami is his deified name.

There is so much to say about Noh, and so much that is Buddhist and Buddhist inspired. Zen and other Buddhist sayings are woven into the librettos. Classical poetry is as well. The metaphysical structure of the Mahayana karma-determined afterlife carries the Zen refinement of the acting intended to produce hana, or flower. Japanese aesthetics is poetic and rooted in Nature. Zeami teaches that using images of the beauties of Nature is a means to artistic elegance; imitating the substance of Nature to reveal the essence of a moment.

Yugen is, like hana, another sophisticated and complex aesthetic term, relying on ambiguity like the perfect mist at dusk. Yugen is a word taken from classical Japanese poetic theory and applied to Noh acting by Zeami. It can be defined thus: “An awareness of the universe that triggers emotions too deep and powerful for words.” In Noh, this is not merely a spiritual attainment by someone contemplating, it is a performed and manifest mental condition, shared with an audience. Noh is among the most lofty arts in the world by this quality alone. Yugen also means “understated elegance.”

Noh master Mikata Shizuka performs Atsumori at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, 2009. Photo by Jonathan Greet. From Core of Culture

Noh master Mikata Shizuka performs Atsumori at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, 2009. Photo by Jonathan Greet. From Core of Culture

What follows is a translation of the nine stages of acting, taken from Zeami’s treatise Kyui, or Notes on the Nine Stages. It is a late and concise work, and the purpose in sharing these stages here is only to show how directly Buddhist contemplative methods and Zen devices are employed to define the style of acting required for Noh. A great Noh actor would know how and when to apply any and each of these performance effects.

These are secret teachings. The term “secret teachings” means different things in different contexts. In Zeami’s case, there were very few copies of his theories and instructions to actors, who danced and chanted their roles. He withheld them from relatives who wanted to usurp the school of Noh he founded. He gave the teachings to another, a mark of true transmission. These teachings of Zeami were not compiled and made public until the 20th century, being virtually unknown, except to Kanze Noh actors, for more than 500 years.

A secret teaching for Zeami meant also that if a professional Noh actor watched you perform Noh using Zeami’s teachings and thereby creating arresting and moving artistic effects, that Noh actor watching would not be able to ascertain how you did it.

Nine Stages does not merely illuminate a system of aesthetic experiences. By anagogical means—a spiritual valuation of the afterlife aesthetic experience— Nine Stages provides the actor a way to approach the otherworldly spiritual reality of the protagonist, usually the aforementioned ghost unable to escape the Wheel of Life and Death and so unable to attain enlightenment. The ground or field beneath all of this is a realization of the impermanence of human life and the insubstantiality of the afterlife in the face of a greater spiritual universe.

Zeami advises actors to imitate Nature, but not its function. Rather to imitate its substance; its ontology, its coming-to-be. It is the substance of insubstantiality, itself a Zen koan. Spring, summer, autumn, winter is the secret of the universe. Continual cycles of regeneration, quintessentially expressed as hana. For Zeami, flower is a powerful and complex term with many applied meanings. In regard to the impression an actor makes, revealing a spiritual state of mind, it implies beauty born outside of time, in a contemplative dimension of consciousness. Hana, a transient “perfect blossom” of shared artistic experience, is produced by the combined arts of dancing and chanting. Hana reveals the spiritual condition of a soul. The actor’s main goal is to create hana in performance, using technique to go beyond it.

Please enjoy the pith teachings of Zeami’s Nine Stages, and appreciate what each would mean as acting advice, performance tips. In Noh there is an interior mental art as sophisticated as the outer technique, something exquisite and refined. The player improves and heightens his state of mind, which is in turn to be manifested in the dimension of technique. The artistic performing technique is never valued on its own; only in relation to the intention and focus of the Mind as it reaches and expresses ever more subtle and spiritual expressions. Note his use of “way,” “art,” and “flower.” To be a Noh actor is to be a spiritual adept.

Yes, these are rarified, recondite, and abstruse teachings by Zeami applied to Noh performance. In London, Noh actor Mikata Shizuka performed for a mixed audience that had never before seen a Noh play and did not speak Japanese. He brought them to tears, and astonished them with beauty.

Noh master Mikata Shizuka ponders the spiritual tragedy of battle during Atsumori at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, 2009. Photo by Jonathan Greet. From Core of Culture

Noh master Mikata Shizuka ponders the spiritual tragedy of battle during Atsumori at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, 2009. Photo by Jonathan Greet. From Core of Culture

Notes on the Nine Stages by Zeami:*

1. The Way of Crude Density, (Lowest of the Low Three Stages)

A flying squirrel with five faculties—competence directly proportionate to inherent ability. A squirrel can fly, swim, climb trees, run, and dig holes.

2. The Way of Dynamic Crudeness (Middle of Lower Three Stages)

A tiger three days after birth already shows a spirited vigor to devour a bull. The energy is dynamic. Eating a whole bull is coarse.

3. The Art of Dynamic Subtlety (Highest of Three Low Stages)

Swift as a hammer flashing through the air. Thrilling as the icy flash of a sacred sword. The heavy strike of the hammer creates the complete precision of the sword.

4. The Art of Young Beauty (Lowest of the Middle Three Stages)

The way deserving to be called "the way" is not an ordinary way. This is the opening line of the Dao De Jing. Its ambiguity toward the world of appearances is the initiatory gate into the full expression of Noh, even if the actor is in the full flower of the beauty of youth. “Where the mystery is the deepest, there is the gate to all that is subtle and wonderful.”

5. The Art of Broad Mastery (Middle of the Middle Three Stages)

Having exhausted an account of what is indicated by the clouds on the mountain and of the moon shining upon the ocean (and indeed, of all things in the universe ). Comprehensive artistic precision is the point of departure for transcendence of all things in the universe.

6. The Art of True Flower (Highest of the Middle Three Stages)

“In the bright mists, the Sun is setting, all the mountains become crimson.”

“In the blue heavens, a spot of bright light, as far as the eye can see, the countless mountains stand revealed in utter clearness.”

This is the shared dawning moment of cosmic unity and one’s place, both transcended into a single performed aesthetic moment. What makes Noh art is the actor’s concern to express his inner experience to others.

7. The Art of the Flower of Tranquil Equilibrium (Lowest of the High Three Stages)

“Heaping snow in a silver bowl. The immaculate vision of lucent white.”

Harmonious immediate equilibrium. The evanescent becomes the most beautiful. Gentleness is true sense, producing hues of spiritual consciousness.

8. The Art of the Flower of Profundity (Middle of the High Three Stages)

“A thousand mountains are covered in snow. How is it then a solitary peak in their midst remains unwhitened?”

A high mountain is as deep. The unifying ambivalence of being and nonbeing, visible and invisible. There is a limit to a mountain’s height, not to its depth.

9. Flower of Peerless Charm (Highest of the High Three Stages)

“At dead of night, the Sun shines brilliantly in shinra.”

Shinra means “to ensnare the deity;” to partake of the divine; to express the living reality of existence, by poetic and aesthetic means. The actor writes on the air with glyphic calligraphy, a wordless poem inscribed by his dancing body, revealing the ineffable glamour of spiritual insight.

Noh master Mikata Shizuka leaves the stage, concluding a performance of Atsumori by traversing the hashigakari, a bridge between dimensions. Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 2009. Photo by Jonathan Greet. From Core of Culture

Noh master Mikata Shizuka leaves the stage, concluding a performance of Atsumori by traversing the hashigakari, a bridge between dimensions. Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 2009. Photo by Jonathan Greet. From Core of Culture

* Translations adapted from J. Thomas Rimer, 1984, and Toyo Izutzu, 1981.

See more

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Pure Land Buddhism in Noh: The Shuramono Plays of Zeami

The Fiction of the Self: Ruth Ozeki

When Dance Transforms

Beauty and Sadness: Reflections on a Japanese Noh Play