If you ever visit a Buddhist monastery, the chances are you will come across some of the happiest people you have ever met. Monks and nuns stroll about their daily routine in graceful, deliberate manner. Their semi-permanent beams, however, reveal nothing as to the Spartan condition in which they live.

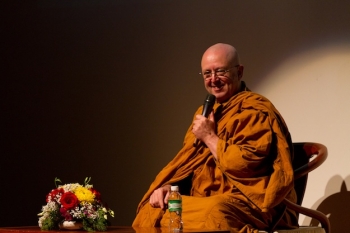

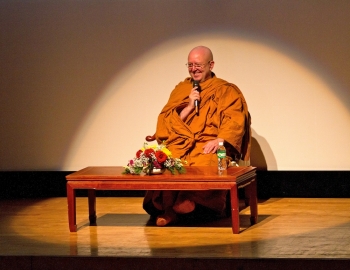

Ajahn Brahmavamso, the Abbot of the Bodhinyana Buddhist Monastery in Western Australia, a Buddhist monk for nearly 35 years, described his typical day, ‘We get up so early in the morning, 3 o’clock in the morning and then we have to go to this cold hall to sit for hours cross-legged, meditating, and doing some chanting. And then only afterwards, maybe at 6.30, we might get a cup of tea, and then you have to work for three or four hours, hard work, before you can get some lunch. And that lunch is just what you’re given, you’ve got no choice, and it’s all eaten in one bowl, all mixed together. So it’s not very delicious at all. And in the afternoon it’s usually more work in those days. And then you can’t watch the television, there is no television or radio, and you can’t follow sport, you can’t play sports, you can’t play music or listen to music. There’s no movies to watch, and there’s nothing in the evening, you can’t eat in the evening, except just to go to the main hall and to sit in more meditation, cross-legged on the hard floor for hours, and when you do go back to your hut to sleep, it’s on the floor, in the cold’ (1).

Despite the arduous daily routine and tough living conditions, if you ever talk to a Buddhist monk, you will, no doubt, be inspired by his enthusiasm and zest for life. His relaxed openness, attentiveness and presence betray the level of his contentment, built on the practice of meditation. In fact, a monk’s practice is to make life a continuous meditation, performing all activities with poised awareness.

Research shows meditation for as little as 10 minutes a day can make a dramatic difference to one’s physical and mental health (2). Hence, more and more people are incorporating meditation in their daily lives. It is being taught in schools, work places and even in prisons.

What exactly is meditation?

There are many types of meditation, such as focusing on the breath, a word or a mantra, or visualisation. It could be done while sitting, walking or even amongst daily activities. In Mindfulness, bliss and beyond (2006), Ajahn Brahmavamso explains, ‘Meditation is the way of letting go. In meditation you let go of the complex world outside in order to reach a powerful world inside. In all types of mysticism and in many spiritual traditions, meditation is the path to a pure and empowered mind. The experience of this pure mind, released from the world, is incredibly blissful’. Meditation is finding the inner peace, by letting go of the things that normally occupy our minds.

Why meditate?

However, meditation is more than just relaxation, it is for personal transformation. In ordinary life, most of us are generally unaware of our negative traits. As a result, we make mistakes and do unintended harm to ourselves and others, by making the wrong decisions and saying the wrong things.

Being mindful of our traits, through careful observation, allows us to ‘know ourselves’. This in turn helps us in taking responsibility for our actions, since we are now more aware of our previous ‘blind spots’. Therefore, we can make better decisions, and enjoy more harmonious relationships.

Meditation increases concentration, awareness, tranquillity, and it sharpens our ability to think. Simultaneously, it reduces tension, fear, restlessness and worry.

Dr Peter Harvey, a professor and meditation teacher in the UK, said ‘The general effects of meditation are a gradual increase in calm and awareness. A person becomes more patient, better able to deal with the ups and downs of life, clearer headed and more energetic. He becomes both more open in his dealings with others, and more self-confident and able to stand his own ground’ (3).

Meditation is relaxing and enjoyable, the Buddha referred to it as ‘pleasant abiding’. Ajahn Brahmavamso, who describes himself as a ‘meditation junkie’, says it is ‘a bliss better than sex’ (4).

Physical and psychological effects of meditation

Most people benefit from meditation even after just a few weeks of practice. Jon Kabat-Zinn at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center, Massachusetts, established a successful eight-week Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program, using meditation to treat stress in patients suffering from a wide range of conditions. The program enjoyed success to the extent that it was later offered to medical students and hospital staff (5).

According to Dr Harvey, ‘Effects [of meditation] are quite established after about nine months of practice, starting with five minutes a day and progressing to about forty minutes a day’ (6).

In The Physical and Psychological Effects of Meditation (1997), Michael Murphy and Steven Donovan consolidated numerous studies (7) from the past few decades of works carried out by researchers on the effects of meditation, they include:

· Lower heart rate

· Redistribution of blood flow (certain types of emotion, such as empathy, is related to the flushing of particular body parts, such as the face and chest)

· Lower blood pressure

· Help with cardiovascular diseases, such as angina and hypercholesterolemia

· Alleviate stress

· Heightened perceptual awareness

· Reduced latate (a substance in the tissue linked to stress) concentration

· Increased reaction time and motor skill (due to increased alertness)

· Increased concentration and attention (less likely to be distracted)

· Improved memory and intelligence

· Increased empathy

· More developed equanimity & detachment

· Increase experience of rapture and bliss

· More vivid dreams. More archetypal dreams. Higher dream recall rate

· Extrasensory experiences, bordering on extrasensory or parapsychological perception

· Altered body image and ego boundaries

· Increased energy and excitement after meditation

· Clearer visual perception and greater awareness of bodily processes

In 1982, Kabat-Zinn demonstrated mindfulness meditation was an effective way to control pain (Silva, 1990). This is because meditators were able to ‘decouple’ the physical sensation from the psychological elaboration.

For most people, a physical pain is usually accompanied by a psychological pain in the form of grief, restlessness and worry. The Buddha likened it to being shot with two arrows. The first arrow is the physical pain, followed by the second arrow, the psychological pain. A wise person, however, only suffers the pain of the first arrow, the physical pain, because he/she can leave out the (optional) psychological pain.

Given the above benefits, it is not surprising that meditation has been used in psychotherapy to help patients develop self-esteem, enhance relationships, and in treating conditions such as depression, anxiety, chronic pain, and childhood distress (8).

What next?

We can all enhance our lives, and those around us, by incorporating meditation into our everyday life. Imagine, what it would be like if everyone meditates?

Learning to meditate is easy. However, for a beginner, it is best to learn from an experienced teacher. Nowadays, there are meditation groups in most local areas, offering cheap or even free lessons. Attending a meditation group is also fun and it offers better support for the practice, especially at the beginning.

References

Ajahn Brahmavamso, Mindfulness, bliss and beyond: A meditator’s handbook, 2006, Wisdom Publications.

Harvey, Peter, An introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, history and practices, 1990, University Cambridge Press.

Murphy, M., Donovan, S., The physical and psychological effects of meditation, 1997, http://www.noetic.org/research/medbiblio/ch_intro1.htm

Padmal, Silva, Buddhist psychology: A review of theory and practice, Current Psychology, Vol. 9 No. 3 Fall. 1990, Pp. 236-254, http://ccbs.ntu.edu.tw/FULLTEXT/JRADM/silva.htm

Websites

Going Forth, http://www.parami.org/duta/goforth.htm

Institute of Noetic Sciences, http://www.noetic.org/research/medbiblio/ch_intro1.htm