The Immortals: Faces of the Incredible in Buddhist Burma – Book Review

By Sarah Carmichael

Buddhistdoor Global

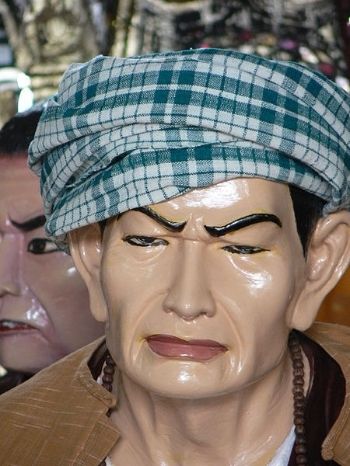

| 2015-10-23 |  Nats and weikza (Taw Bo Bo Aung, Bodaw Aung Min Gaung), Mount Popa, Burma. From commons.wikimedia.org

Nats and weikza (Taw Bo Bo Aung, Bodaw Aung Min Gaung), Mount Popa, Burma. From commons.wikimedia.org“Tuesday, September 30, 2003, 7:00 pm. The apartment, which is located on an avenue running along the moat of Mandalay’s palace, is suddenly plunged into darkness”—this dramatic opening tells us that this book is no conventional academic analysis. Authored by Guillaume Rozenberg, a researcher and member of the French National Centre of Scientific Research at the Centre of Social Anthropology in Toulouse, France, the book is a discussion of weikza (the “Immortals” of the title), human beings in Burmese Buddhism who have acquired superhuman powers, including the ability to fly and to prolong their own lives.

As well as protecting and propagating Buddhism, weikza are concerned with the spiritual and material welfare of the community. Rozenberg focuses on a cult centered on Mebaygon Village in central Burma* where, in 1952, a young, semi-literate peasant became possessed by a weikza. The cult of this weikza and his three superhuman companions has since attracted many followers from all walks of life, and in regular gatherings in a monastery in Mebaygon, the four weikza both speak through their medium and appear in the flesh in front of large crowds.

The book explores the weikza cult from different angles. Rozenberg begins by telling a story from the late 1950s, when Hpay Myint, the newly appointed district officer for religious affairs in Minbu, central Burma, went to investigate the cult of the four weikza in Mebaygon Village. The narrative then fast-forwards to 2004, when the author attends a “sermon” given by the very same weikza, where he witnesses similar prodigious feats to those recounted by Hpay Myint. The author embarks on a series of journeys with one of the cult’s main disciples, visiting various centers of the weikza cult and interviewing key figures who tell him stories of their experiences. The intrepid anthropologist and his companions roam around the back roads of central Burma, fording swollen rivers, encountering troublesome bureaucrats, and occasionally losing the reader as the narrative switches backwards and forwards in time.

This combination of story-telling and travelogue makes for an absorbing, though sometimes confusing, read. Interspersed within the narrative are wide-ranging discussions on different aspects of Burmese religion and society. One such discussion focuses on whether the weikza’s supernatural powers are derived from magic or religious practice. This question is put to both members of the cult and monks who are strongly opposed to it. None of the informants question the existence of supernatural powers, which are believed to be obtained as a result of an extended period of contemplation and meditation, or via magical intervention from an external source, such as a tree spirit. The second method is regarded as “mundane,” and inferior to the first, “supramundane,” method, which involves a high level of spiritual accomplishment. The debate among the Burmese informants is whether the weikza’s powers can be characterized as mundane or supramundane. Cult members, of course, believe that the weikza’s powers transcend the mundane.

The discussion then widens to a consideration of the role that supernatural powers play in Buddhism. Rozenberg claims that many Buddhist commentators have tended to ignore or downplay accounts of prodigious or miraculous feats in the Pali texts, preferring to present a sober and rational, and even scientific, view of Buddhism, stripped of all numinous features. This tendency can also be observed in the rise of secular Buddhism in the West in recent years, and in the various projects to establish a scientific explanation for what happens in the minds of meditators and to apply what is learned from such experiments in secular contexts. Rozenberg contends that accounts of miraculous powers of the Buddha are at the heart of the original texts rather than being later, culturally biased accretions, and that superhuman powers are inherent to the role of the historical Buddha.

Some, but not all, cult members aspire to become weikza themselves, and among those who do, alchemy is a common practice. These dedicated disciples attempt to use fire to melt and mold metals into “energy balls,” a practice which is taken as a form of Buddhist meditation in which purification of the individual accompanies purification of the alchemic substances. The struggles and many failures of these disciples are recounted with both sympathy and humor.

The relationship of the weikza cult to other religions is also discussed. Cult members display similar attitudes to other Burmese Buddhists: Buddhism and “Burmeseness” are seen as interwoven, with other religions occupying various positions on a cline of difference. Islam is seen as the most distant religion from and posing the greatest threat to Buddhism, despite there being no factual evidence that this threat actually exists. This scapegoating of Muslims continues, most recently with attempts to draft legislation to restrict marriage between Buddhist women and Muslim men, and to prevent conversion to Islam. The weikza are described by their disciples as great converters of Muslims, though Rozenberg finds few examples.

The second half of the book is more tightly structured than the first, focusing on three main themes: the phenomenon of possession by a weikza; the quest for invulnerability and superior strength by some cult disciples; and how the weikza prolong their lives.

Possession by a weikza involves no special costume, music, or dance, with only the voice quality and register of the medium’s speech being affected. The mediums described are from undistinguished backgrounds, with the only common feature being an experience of bodily dysfunction, which a weikza cures, after which the medium serves as a kind of radio receiver for the weikza’s transmissions. Apart from speaking through a medium, at other times the weikza appear in the flesh to communicate with their audience, often entering a room by flying through a high window or appearing out of thin air.

The Tactical Encirclement Group is a martial arts troupe which has arisen from the weikza cult. Members of the troupe, who are generally unemployed, rural young men, gain invulnerability and superhuman strength by observing the Five Precepts and swallowing pieces of paper with cabbalistic diagrams on them, drawn by a martial arts master and disciple of the weikza. They then travel the country, giving demonstrations of their prowess. The troupe provides a safe haven for vulnerable young men prone to violence and alcohol abuse, but Rozenberg sees a disturbing tendency towards totalitarian ideology in the group’s emphasis on preserving racial purity and promoting “Burmeseness.”

Weikza Bo Min Gaung, Mount Popa, Burma. From

commons.wikimedia.org

Despite possessing superhuman powers, the weikza remain human beings, albeit with extremely long lives. The lifespan of a weikza is supposed to be no more than 1,000 years, although a senior weikza described in the book has already reached the age of 1029. The final chapter of the book describes how weikza prolong their lives by means of an elaborate ceremony: the “trial by fire.” A detailed account of a weikza life-prolonging ceremony in 1975 is given and the book ends on something of a cliffhanger, with an account of the preparations for an upcoming ceremony. During the course of these preparations, the weikza’s medium is arrested and spends a year in detention. Even though the weikza cult in many ways conforms with widely accepted social norms, for example in the propagation of Buddhist values, Rozenberg believes that the authorities are suspicious of the cult for fear of it providing an alternative popular voice to state-sanctioned communications.

Unusually for a scholarly work, the author often speaks directly to the reader and early on states that rather than aiming for a linear, scientific exposition, the book is organized around the thinking and writing processes at different stages of his research project. The narrative sometimes rambles, taking us into the byroads of contemporary Burmese life. For example Chapter 4, ostensibly about the martial arts troupe, opens with a description of an elderly, much repaired, monastery jeep, which leads to a discussion of government policies on the import of cars. Rozenberg also discusses the ethics of his research: he gains access to the cult so easily because the disciples believe him to be precisely the kind of sceptic that the weikza can convert, a belief that he has no intention of fulfilling. On one occasion, a disciple whom he respects greatly asks him not to publish certain information. He considers this—and publishes anyway. In the final analysis, his role as an anthropologist trumps his role as a friend.

The Immortals is a fascinating account of a major religious phenomenon in Burma. As well as telling a good story, the book touches on important social and religious issues of interest to both the general reader and a student of Burma or Buddhism.

*Burma, rather than Myanmar, is used in the article as this is the term used by the author.

Sarah Carmichael teaches at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

The Immortals: Faces of the Incredible in Buddhist Burma was published by University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, in 2015.