FEATURES|COLUMNS|The Five Wisdoms

The Mystery of the Five Elements

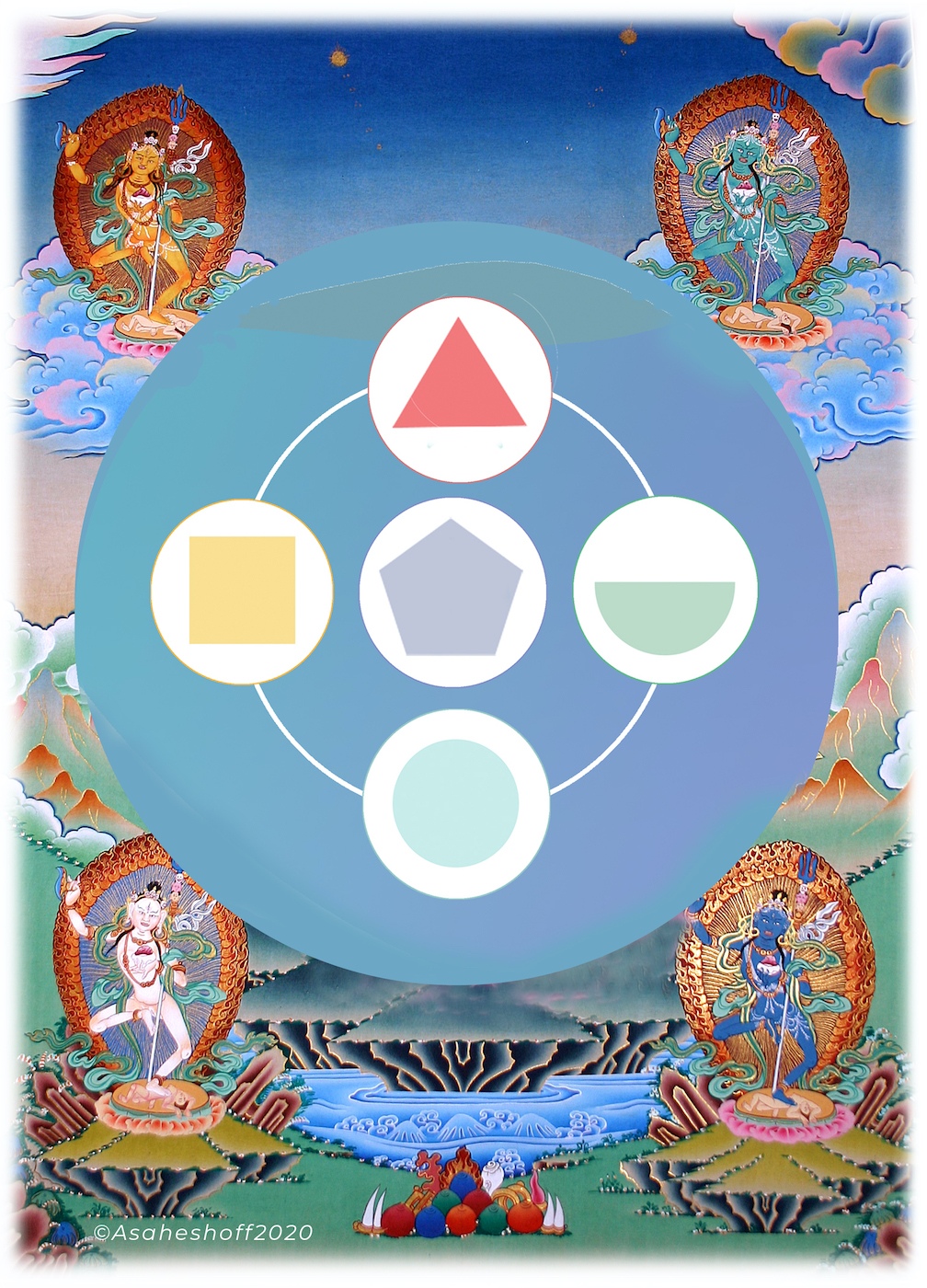

Elements and dakinis. Image courtesy of Asa Hershoff

The elemental conundrum

The five Elements are the very bedrock of Vajrayana. Which makes it all the more extraordinary that, to date, there has been no attempt to define more precisely what these phenomena are, and how they exist as principles that structure our entire world. Those master yogis and yoginis who have achieved an inner realization of the Elements should have more to say about them and the part that they play in our bodies and minds. Some may proclaim that all that is needed is to learn the tradition, follow the practice, and receive the fruition. This is true, as the illustrious history of highly realized beings within Vajrayana demonstrates. But there are also shortcomings to this approach, especially for the West.

The need for renewal

All impactful and significant innovation and discovery, including spiritual truths, become increasingly codified and structured. Likewise, Vajrayana follows a set of highly structured dogma, creeds, and ideologies. Those boundaries serve a useful purpose in keeping the integrity and meaning of a spiritual path intact. Group culture and modes of thought and action need to be preserved, but they can also become excessively dogmatic, canonized, and rigid. Ultimately such systems may become a lifeless husk, instead of a living, evolving organism. That is the tightrope of human striving. One way to keep a tradition from becoming petrified is the healthy encounter with new thought, fresh insight, and the experiences of those who plumb the depths of the tradition, and then bring new pearls of wisdom to the surface. This is the wellspring of new growth and evolution, and the defense against losing the essence while merely maintaining the outer facade of the tradition.

Western mind 2.0

We do have a square-peg-and-round-hole situation with Western Buddhism. Those who have traveled and immersed themselves in Eastern life know how profoundly and essentially different the shape of the mind can be in different cultures and epochs. The interface of Buddhism with modern physics and psychology are two prominent attempts at bridging the gap between how we experience life today, and that of 10th century Tibet or fifth century India. These dialogues look for similarities and common ground or for confirmation, but do little to explain or expand on the crucial points of ancient knowledge. The West seeks understanding from the outer world, while the East specialized in inner exploration. A possible bridge to integrate the language of the inner self and that of the outer world is none other than the Five Elements.

Here we are not trying to solve the riddle of the Elements, but to examine different ways in which we might approach them. This can only enhance our path of inner development. A deeper Elemental understanding also enhances our ability to heal body and mind, to benefit others, and repair the landscape we inhabit. This fulfills what in Buddhism is called the “two benefits” of self and other, because apart from spiritual unfoldment, Elemental work can also be used to treat trauma, illness, mental stress, and anxiety, and shift how we view our place in the world.

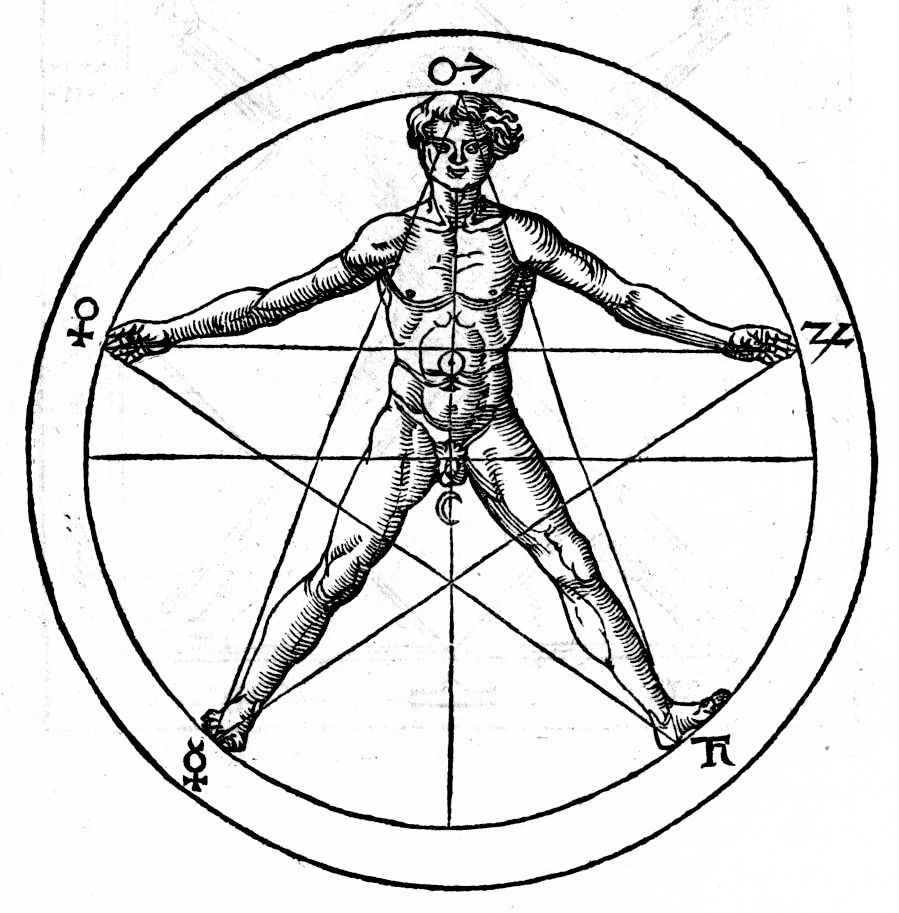

Image courtesy of Asa Hershoff

1. Elements as metaphor and archetype

The Elements stand as an elegant statement about human potential and the human condition. They are symbols, living representations of a specific set of circumstances, qualities, attributes, and liabilities. They represent archetypal patterns, forces, and states that speak to us directly. The stability and weight of Earth, the immediacy and presence of Fire, the dynamic flow of Water, are not just concepts, but experiences that we can relate to on multiple levels. Especially, they are not superficial or peripheral, but central to our being. Plato spoke of Forms, eternal principles that stand behind our perceptions, just as physicists seek the core principles to explain what is behind phenomena. The Five Elements model similarly encompasses both outer and inner sources of experience. These archetypal meanings are, by nature, both multifaceted and multilayered, requiring study and direct work with Element forces themselves to unlock their secrets—and their power.

But even on a superficial level, the five-point star carries great weight, symbolically representing the wholeness of the human as incarnate spirit. Its use on coins and architectural objects goes back at least 5,000 years to Sumeria and Egypt. The Greek Pythagoreans used it as their main symbol, arrayed with syllables of the five elements, spelling out the goddess “Ugieia” or Hygeia, meaning wholeness/health. It is a perennial and global icon, the five-pointed star appearing on more than 60 national flags and in every form of art, decoration, and advertising. A “five-star” review is a pale reminder of the inner meaning of this holistic archetype.

2. Elements as organizing principle

A useful and practical way of thinking of the Elements is simply as an organizing principle or template. This is, after all, what science, philosophy, and religion are looking for. But models can be purely artificial or they can reflect an organic reality. We can help confirm the validity of the Elemental model because of its almost universal application. The more useful it is in organizing our perception, the more it appears that reality itself is formulated in this way. Indeed, the Elemental template was applied to health and illness millennia ago, through the ancient sciences of Ayurvedic and Tibetan medicine. And it impacted psychological understandings from the time of Galen until today with the (truncated, yet still useful) four-Element system of the Temperaments, Jungian types, and so on. In the East, it has been applied equally well to a quintet of environmental forces and forms, demonic obstacles, ritual activities, architecture, art, spiritual unfoldment, pure realms, and consciousness itself. Learning to perceive this five-fold division is an exercise in itself, and one that can be deeply enriching.

3. Elements as mathematical core

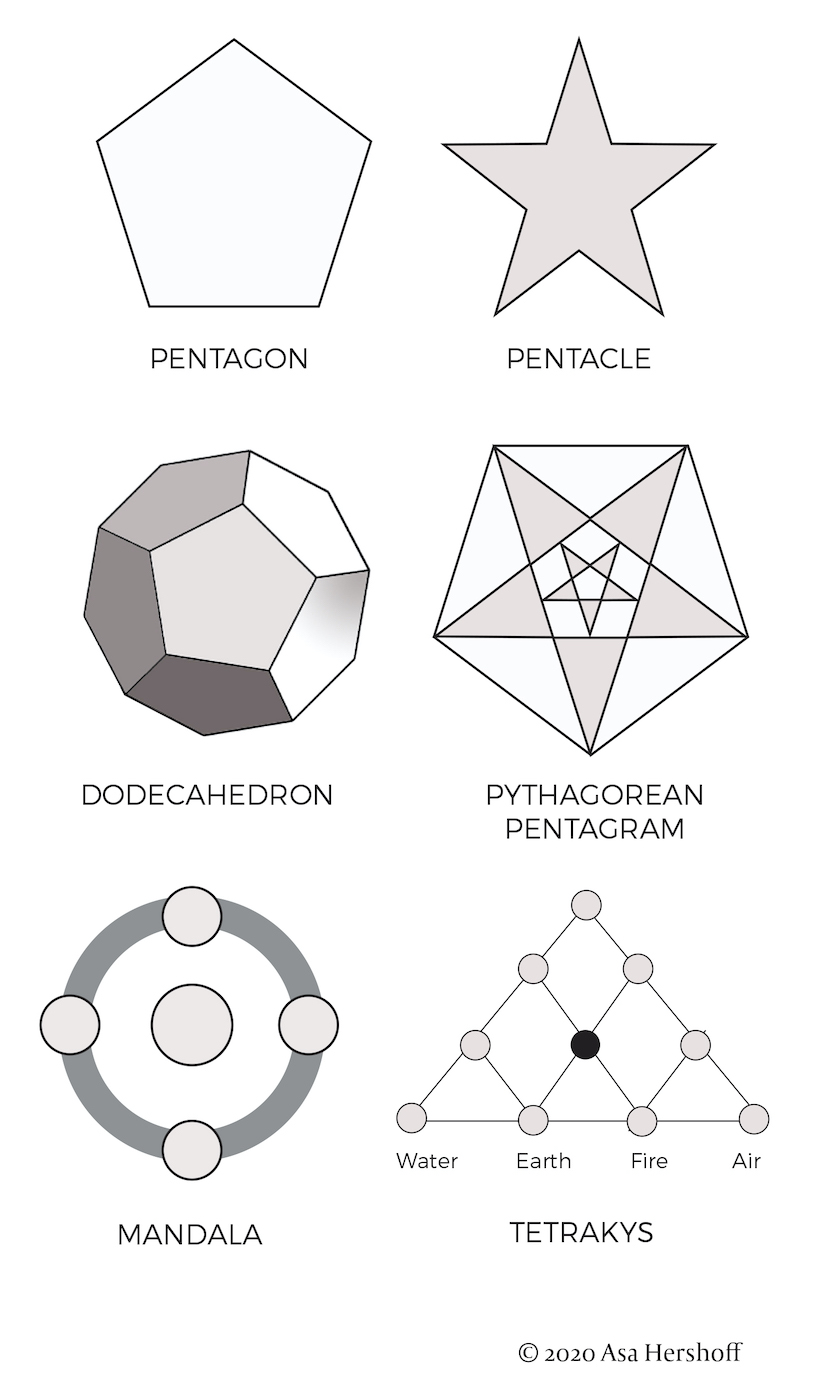

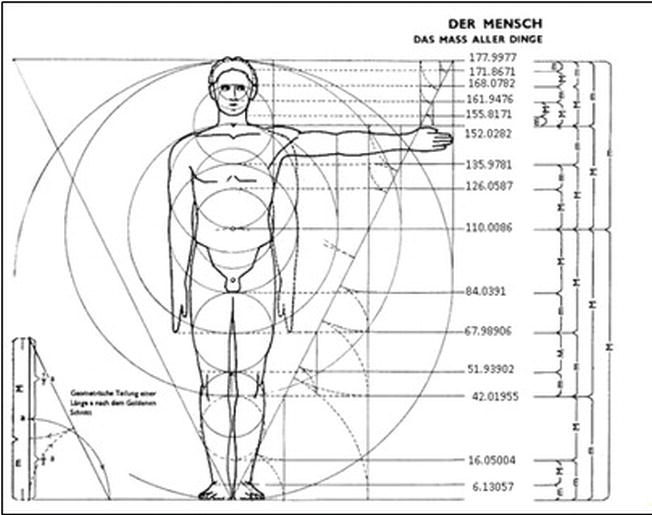

The form of the pentagon (five-sided polygon) and pentagram (five-pointed star) have fascinated humanity for millennia. This is partly because they perfectly embody the Golden Ratio, or phi, and the Fibonacci sequence of numbers or spiral that is found throughout nature, art, and architecture. That ratio of 1:1.618, exists in most of the proportions of our body, including the eye and ear (see the diagram), in shells, sunflowers, insects, the DNA spiral, frogs, the curve of galaxies—everywhere. It is found in the pyramids of Giza, the art of Leonardo da Vinci, and the pagodas of Japan. And it is the basis of our musical notation system and a large part of our sense of beauty and harmony in general. Five is intimately related to phi as a mathematical formula as well as a geometric form. Making the five-sided figure into a solid, we have the dodecahedron, replicating the golden mean to infinity. There are even current cosmological models that consider the universe itself to be a complex dodecahedron.

These geometric figures and their associated mathematics were directly associated with the Elements by the ancients. Pythagoras taught that the entire universe was a mathematical structure, for which he used the tetractys to explain the meaning and import of the numbers 1–10 (see illustration). In this model, five is the central and most important; The tetractys diagram itself contains various phi ratios and displays how the monad or spirit moves down to create the four lower elements. It seems clear that Pythagoras learned the five-Elemental and mathematical mysteries from his long apprenticeship in Egyptian temples and his Brahmanical and Buddhist studies either in India itself or gymnosophist teachers among the Egyptians and Babylonian magi.

Image courtesy of Asa Hershoff

4. Elements as psychological template

The correlation of the Elements with the psyche as presented in traditional Buddhism is, unfortunately, rudimentary. Furthermore, it seems like an artificial force-fit of pre-existing Buddhist concepts with the emergent five-element insights that had arisen through direct tantric experience. Initially, there was no connection between mental defilements (Skt: kléshas, Tib: nyön mong) and the Elements. But they became aligned in an effort to integrate classical Buddhist Mahayana and Sarvastavadin thought with Vajrayana concepts. The lists of emotional neuroses from which these five were drawn were by no means consistent. Different texts within the Abhidharma list five, six, and 10 kléshas, while the older Hinayana texts have a different set of five, more related to the monk-meditators’ obstacles. The contemporaneous Hindu tradition has several different lists as well, from the yogic school of Patanjali, the Nath Siddhas, and the Samkya tradition and its complex tattva cosmology. Most importantly, in my opinion, is that the accepted standard list that became canonized in Buddhism does not jibe with the Western ideas of Temperament that evolved from Aristotle, Hippocrates, and Galen. Note too that kléshas only purport to represent a distorted or neurotic aspect of the Elements. Missing is the description of “healthy” or normal Elemental mental characteristics. This however does find some expression in Ayurvedic and Tibetan medicine. Here too we are hampered by the three-guna system that squishes the five elements into only three categories, with no real justification. Thai Ayurveda, representing the original Buddhist system, has maintained the five-Element approach, and informants in India say that the three-temperament system of Indian Ayurveda is a clinical approach that simply ignores Space and Earth, in order to focus on Water, Fire, and Air as the cause of the majority of acute symptoms. In spite of all this historical confusion, we can begin to understand the mentality of the Elements by correlating their characteristics and qualities with the vast resource of Western psychological knowledge and observation, from early philosophers to Shakespeare and onward to cognitive and humanistic schools of psychology.

5. Elements as energy

The elements are formative principles, but they are not merely organizational frameworks. They act, they impact, they cause things to be put into motion. They are a force, and that force is tangible. In the world of material science the outer “objective” facts are what is important. On the path of inner exploration and transformation, the “subjective” reins supreme. They are both a form of science, neither one better than the other, but working in very different contexts. And so the goal of Element practice is actually to sense these five individual energetic qualities in your own body and mind, and in the world around you.

Both Indian and Tibetan medical texts and meditation teachings talk of the five winds (vital or subtle energy, prana, or chi) and five fires. Vajrayana provides great detail in terms of working with these energies through the mental access points of sound, light, and form. We learn to listen to, and move these energies, through channels, energy centers, and body tissues. However, traditionally their individual characteristics are not described, though as an exception, the great sage and polymath Tongtang Gyalpo does allude to their heating, cooling, and other qualities. Even Chinese qi gong or neidan, with its sophisticated knowledge of bioenergetics, does not ask the meditator to explore their “elements” (which are actually phases or processes) in any detail. However, the practitioner should and must train in differentiating these energies and their relationship to bodily process (physiology), psychology, and spiritual alchemy. From their the Elemental energies will be also perceived in other people, and in all objects, animate and inanimate.

6. Elements as spiritual anatomy

For the Buddhist, Hindu, and yogic traditions, the main interest in the Elements is their relation to our spiritual anatomy, and transforming our impure elements into their original, inherently pure “wisdom” form. Fortunately there is an established relationship with the specific centers where these elements reside in an accessible fashion—the chakras. More than indwelling components, tantric embryology tells us that these energy centers are formed first, with the physical body congealing around them. In terms of our attempts to define or characterize the Elements, this adds a new dimension. Now they are not only components of our biology and physiology, but present in a higher, more refined form. This connotes the primary or original form of the elements, their “divine” or highest level, which can transform our ordinary state, suffusing it with their pristine qualities. We live in a step-down world, where we are a pale reflection of the infinite and timeless consciousness which pervades all. Our job is to climb back up the ladder, albeit against the current of biological life. Here we use mantric sound and visualized lights and syllables as part of the methodology.

Image courtesy of Asa Hershoff

The elemental bottom line

Clearly, modern science has yet to discover a set of five “somethings” corresponding to the five elements. While this may be unfortunate in terms of explaining these long-standing concepts, it is likely a very good thing for the survival of the human race. If the knowledge of how to manipulate the five organizing forces of reality were in the technologically sophisticated, but ethically, morally, and spiritually stunted hands of science, technology, commerce, and politics, the timeline of our demise could be greatly accelerated! It is not for nothing that these powerful truths were closely guarded secrets of the Egyptians and followers of Pythagoras, and no less so the tantrics of India, Tibet, and Bhutan, until our present day.

This is the razor’s edge. All religion moves toward entropy, toward extinction, unless renewed from within by the same spiritual forces that enlivened it in the first place. We must enliven and evolve what the five Elements mean in the context of our modern mind and strangely configured culture. For spiritual seekers, the pressing issue is not politics, not ecology, not cultural shifts, or social movements. Maintaining the original vision and purity of the Source (which goes by many names) and its five-part Elemental expression, without it being co-opted by fear, doubt, ignorance or inflation, is the greatest challenge of our age.

References

Frawley, D. 1997. Ayurveda and the Mind: The Healng of Consciousness. Twin Lakes: Lotus Press.

Komzsik, L. 2018. “The World of Five: The Universal Number.” www.trafford.com (2013)

Meisner, G. B. 2018. The Golden Ratio: The Divine Beauty Of Mathematics. New York: Race Point Publishing.

Pearse, R. “Pythagoras in India?” 17 November 2009. Retrieved from: https://www.roger-pearse.com/weblog/2009/11/17/pythagoras-in-india/

Saati H, and J. Aghakazemi. 2018. “Relationship between structures of C5C7 Carbon Nanotubes and geometry of ornamental.” Journal of Mathematic Stat 1: 102

Wangyal, T. 2002. Healing with Form, Energy and Light: The 5 Elements in Shamanism, Tantra and Dzokchen. Ithica: Snow Lion.

Wheeler, K. L. Pythagoras, 2005. Plato and the Golden Ratio the Golden in the philosophy of the Pythagoreans. New York: Dark Star Publications.

See more

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Light Body Practice: First Stages

Chöd in the Time of Pandemic

The Missing Self in Buddhism and Psychology