FEATURES|THEMES|Travel and Pilgrimage

The Pagoda of Vincennes: A Living Buddhist Mosaic

The Pagoda of Vincennes. From wikipedia.org

The Pagoda of Vincennes. From wikipedia.orgWhen I lived in Paris, I often went to the Himalayan and Tibetan festivals held every year at the Pagoda of Vincennes. The scenery is peaceful and romantic, with its greyish lake and woody scents, its open sky, its undulating ducks and swans, artificial grotto, cascade, island, and rotunda, designed by the 19th century French architect Gabriel Davioud, famous for its monumental and eclectic Parisian buildings. The park is very close to the buzzing heart of the city—accessible by the Paris Metro—yet it is so detached in style and atmosphere. Hyperactive Parisians go for a jog in the early morning, tired families come for a rest on Sunday afternoons, enthusiastic lovers seem to stay for ever. There stands the Pagoda of Vincennes, a vestige of the French 1931 International Colonial Exhibition, now the seat of the French Buddhist Union. It is a place full of complicated histories, memories, and ambitions.

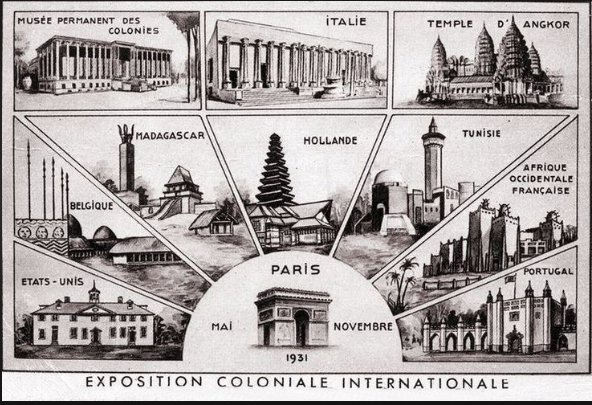

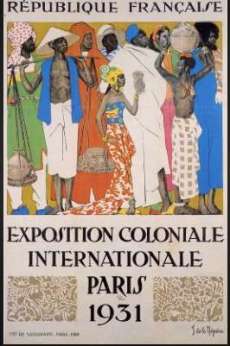

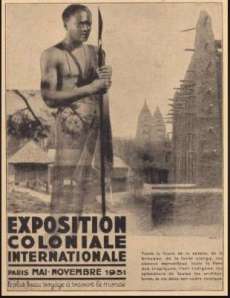

A postcard from the 1931 colonial exposition. From pagesperso-orange.fr

This 28-meter-high building was not located in the Indochina section of the exhibition, as one might have expected. Instead, it was located in the African section, with five other secondary bungalows that no longer exist. Originally, the “Great Pagoda” was in fact the “Cameroon Pavilion.” It was built as a big West African house, with wooden beams, earthen walls, and a thatched roof. It therefore does not look like an Asian building at all.

The history of the transformation of the Cameroon Pavilion into a Buddhist temple, which now contains relics and one of the highest Buddha statues in Europe, is quite complex and owes much to the accidents of France’s history, politics, and religious life. When the six-month-long, highly successful Colonial Exhibition was over, some of the buildings remained in place to testify to France’s political influence in the world. Among those, a few monuments became the Museum of the French Colonies. In 1960, with the fall of the French colonial Empire, it became the Museum of African and Oceanian Arts, and remained so until very recently. The Cameroon Pavilion was restored several times, until it was altered for the practice of Buddhism in 1977.

The goal was to enable Asian people from the former French Indochinese regions to practice their own religion in the French metropolitan area. Indeed, due to the bloody events that took place in Vietnam and Cambodia in the 1970s, many took refuge in France, but had no place to celebrate their culture. To remedy this lack, the French official Jean Sainteny, who had served in Indochina and had founded the International Buddhist Institute, suggested that the Cameroon Pavilion might serve as a place of worship and of gathering for various Buddhist traditions. Since then, the building has served as such, and is now also the seat of the French Buddhist Union, which aims to represent all Buddhist schools present on French soil, defending Buddhist ideas and values, and maintaining good communications with the French government.

From pagesperso-orange.fr

From pagesperso-orange.fr From pagesperso-orange.fr

From pagesperso-orange.fr From pagesperso-orange.fr

From pagesperso-orange.fr From pagesperso-orange.fr

From pagesperso-orange.frAs a shared, almost neutral (and highly original) Buddhist place, the Pagoda serves as a platform for various agendas. The French Buddhist Union’s yearly program is very dynamic and includes activities for many Asian Buddhist communities. In one year, one can indeed celebrate Vesak the Sri Lankan way, receive teachings from the Venerable Jetsun Khandro Rinpoche, celebrate the traditional Cambodian New Year, attend a charity meeting in favor of Cambodian orphans, join a gathering of Tibetan exiles, attend the Monlam Festival with another Rinpoche, and visit a thanghka exhibition, a Nepalese craft fair, and a “sacred art” exhibition. One can also join the celebrations for the Dalai Lama’s birthday, receive guidance in the practice of mindfulness meditation, pray for the deceased with the Sri Lankan and Cambodian communities, welcome Cambodian monks at the end of their retreat, listen to Tibetan chants, learn about the Mongolian way of life, watch Tibetan monks perform a cham dance, or make a colorful sand mandala.

Despite the political relationships that have long existed between France and Southeast Asia, in particular Vietnam and Cambodia, the predominance of the Tibetan community is noteworthy. Indeed, although there have been no official, longstanding political connections between France and Tibet, the presence of various Tibetan associations—either humanitarian, cultural, religious, or commercial—at the pagoda far exceeds that of other communities. This can be seen in two important facts.

First, there has been a Tibetan Buddhist temple a few meters from the pagoda since the early 1980s, whereas no similar place has ever existed for other exiled communities. In fact, this “temple,” named Kagyu Dzong and founded by Kalu Rinpoche in 1974, is more of a Dharma centre for French practitioners than a place of worship for Tibetan exiles—who, by the way, do not account for a major portion of French immigration. When I talked to many of them during Himalayan festivals, they always told me that they never went to Kagyu Dzong, and that it is primarily for Western practitioners. They were not very interested, they said, although they found it great to have such a place. When asked about their spiritual practice, they either replied that they did not have time to go there, because they lived too far away and preferred to pray at home in front of the family altar, or they confessed that they did not care much about religious practice. Notwithstanding, Kagyu Dzong offers many activities with a variety of French and Asian teachers, and receives many important guest lamas for teachings and initiations. People can thus learn the basics of Buddhism and meditation, take a yoga or a Japanese calligraphy class, join the sangha for a morning Green Tara or Medicine Buddha practice, or a Chenrezig ritual, take a Tibetan language lesson, bring their kids to an easy meditative activity, or follow a weekend seminar on emotions with a French psychoanalyst. In the minds of the locals, as it appears from my field research, the Cameroon Pagoda is definitely Tibetan.

Second, the most famous and successful event on the pagoda’s calendar is without a doubt the Himalayan and Tibetan Festival, also called the Festival of the Tibetan Cultures, thus making a Tibetan mark on the former territory of the Colonial Exhibition. This festival takes place each year in June and is organized by La Maison du Tibet, an association dedicated to the promotion of a “Free Tibet.” This promotion is made by the association and displays, in one place, the most important “pillars” of Tibetan culture (according to the organizers): craftsmanship (mostly silver, turquoise, and coral jewels, incense, silk scarves, and bags), performing arts, whether religious or profane (purification rituals, cham dances, sand mandalas, the chanting of prayers, folk songs and dances, Tibetan pop music), visual arts (thangkas, bronze statues, contemporary art), momos and butter tea, meditation, “healing yoga,” contemporary poetry, traditional medicine, Tibetan dogs, and the screening of documentaries on the Himalaya or on the political situation of Tibetans. This colorful and lively event has become a major tourist attraction for both Parisians and overseas visitors, and an important source of revenue for the Tibetan exile community.

From pagesperso-orange.fr

The Pagoda of Vincennes is a unique Buddhist monument, not only in France but probably in the whole world. Strange at first sight, with its unmistakable African shape, it becomes even more intriguing when one discovers its history, its current functions, and its physical surroundings. The Great Pagoda crystallizes some of the most complicated cross-cultural heritages and influences: colonialism, war, exile, the fight for the independence of one’s people and their cultural survival. In a way, it is a condensed samsara, a place of materialized suffering and of great hope. The Great Pagoda is definitely worth a visit.

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

The Guimet Museum in Paris: A Legacy of Asian Art in France

Meritorious Gifts at Tibetan Buddhist Centers in France: Some Paradoxes

From Chamonix to Chenrezig and Thangkas to Mountain Landscapes – The Story of Neljorma Tendron

Jacques Bacot’s Rebel Tibet, Part Three: Buddhism in Interwar and Postwar France

“Eclectic Buddhism”, a French Fin-de-Siècle Eccentricity

Related news from Buddhistdoor Global

Guimet Museum in Paris Hosts Historic Exhibition, “Buddha, the Golden Legend”

Korean Buddhist Cuisine Helps France and Korea Celebrate 130 Years of Diplomatic Ties

Buddhist Climate Change Statement Delivered to President Hollande