FEATURES|COLUMNS|Ancient Dances

The Secret Life of Collections

Ceremonial tsam mask. From the Milan Klečka collection. A tourdag mask of a burial grounds protector. A pair of protectors defends the dance ground. They wear dresses decorated with a skeleton pattern, with colorful fans on the sides of the head, so-called “butterflies.” In the background, the mask of the god of war. Photo by Jakub Šedý. Image courtesy of the Náprstek Museum

Ceremonial tsam mask. From the Milan Klečka collection. A tourdag mask of a burial grounds protector. A pair of protectors defends the dance ground. They wear dresses decorated with a skeleton pattern, with colorful fans on the sides of the head, so-called “butterflies.” In the background, the mask of the god of war. Photo by Jakub Šedý. Image courtesy of the Náprstek MuseumThe Náprstek Museum of Asian, African and American Cultures in Prague has opened a new exhibition: The Secret Life of Collections, Mongolia and Buddhism. The exhibition is institutionally reflective, being a representation of the museum’s own collecting from Mongolia in the 19th and 20th centuries. This marks a period when world cultures, extant and vanished, began to know of each other, driven by curiosity and the opportunity to understand more about religion and art, science and commerce, in societies other than one’s own.

This includes a time before anthropology, before anyone knew of King Tut, when nascent archaeology was discovering for the first time the physical remnants of societies, otherwise known only through writing and lore. The collecting period continues through to the 1960s and 1980s, when guest specialists from Czechoslovakia working with Mongolian counterparts were able to collect and thereby save Buddhist objects. The collection reflects the high-mindedness of educated and adventurous Czech citizens over the span of 100 years.

This period also covers two world wars, the wholesale destruction of Mongolian culture by the Soviet expansion beginning in 1924, and the advent of industrialization. What is remarkable about this exhibition is its evidence of inter-cultural meaning by stewarding objects that could have been destroyed in both Europe and Mongolia. Buddhism was effectively wiped out in Mongolia after centuries of noteworthy Buddhist practice and expression. The Náprstek Museum’s efforts to display objects from their Mongolian Buddhist collection gives us cause to re-visit Buddhism in Mongolia and its interactions with people from around the world.

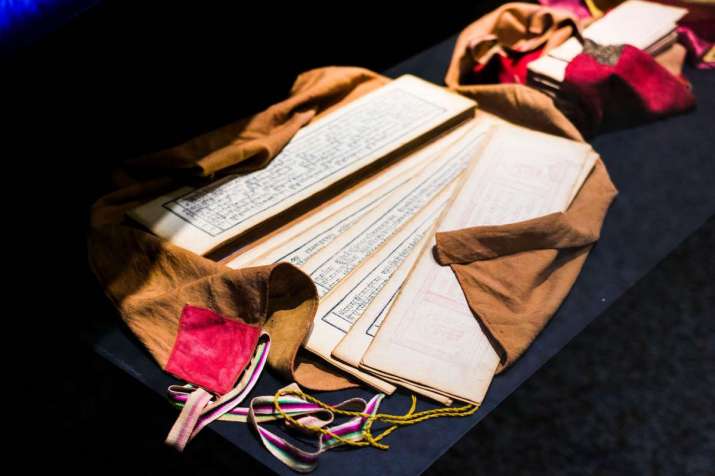

Buddhist scriptures from Mongolia held in the Náprstek Museum, Prague. Photo by Jakub Šedý. Image courtesy of the Náprstek Museum

Buddhist scriptures from Mongolia held in the Náprstek Museum, Prague. Photo by Jakub Šedý. Image courtesy of the Náprstek MuseumBuddhism reached Mongolia in the first century CE, and so its break in the 20th century was the death of nearly 2,000 years of Buddhist practice. It also marks a timeline of various types of Buddhism. In the 13th and 14th centuries, the Yuan dynasty ruled China. This was a Mongol court that adopted Buddhism as the preferred religion of the ruling class. The Tibetan form of tantric Buddhism with which Mongolia is most associated did not arrive until the 16th century, when Mongolia and Tibet developed strong ties. Even the title “Dalai Lama” is Mongolian, bestowed upon and affirming theocratic rule in Tibet for hundreds of years. The title is a product of those intense times.

Mongolia is rebuilding its culture and Buddhist practice presently, beset by enormous pressures from China and the United States, although freed from Soviet tyranny. The absence of Buddhism is palpable in the capital Ulaanbaatar, where one monastery functions, although no monks live there. This is a critical impediment to the transmission of practice. They perform rituals, and museums there must include Buddhism to tell the story of Mongolia’s history. But living Buddhism is on wobbly legs after being wiped out.

Garuda mask and tsam robe in the exhibition space. Photo by Jakub Šedý. Image courtesy of the Náprstek Museum

Garuda mask and tsam robe in the exhibition space. Photo by Jakub Šedý. Image courtesy of the Náprstek MuseumMining for minerals has been a source of Mongolian wealth for generations. It has also been the source of foreign nations taking advantage of Mongolia. Being so large, it is difficult to police. Even today, Mongolia is the top rare-earth metals mining location in the world. Czechoslovakia’s collecting in Mongolia began with mining engineer Hans Leder (1843–1921), who was also an entomologist, a researcher of insects. His breadth of knowledge encompassed culture, the natural world, and industry. Mongolia was a splendor of all these things. Leder made several trips to Mongolia over the turn of the century, creating a venerable collection that was ultimately shared among many museums in Europe. Part of the Leder collection was given to the oldest museum in the Czech Republic, the Silesian Museum in Opava. After World War Two, some of these objects were moved to the Náprstek Museum and are now on public display.

The story of Czech collecting continued with archaeologist Lumir Jisl (1921–69) and linguist Pavel Poucha (1905–86 ). Inspired by Leder, Jisl visited Mongolia, learning history and studying the art. Poucha also visited Mongolia and in the 1950s translated one of the most important books in traditional Mongolian literature, the 13th century Secret History of the Mongols. These two men mark a breakthrough in Czech liberal arts and knowledge of the world, and together brought a new professionalism to cultural understanding.

Ceremonial tsam mask of Begtse, the pre-Buddhist Mongolian god of war. The red mask, decorated with beads, represents power and strength. From the Milan Klečka collection. Photo by Jakub Šedý. Image courtesy of the Náprstek Museum

Ceremonial tsam mask of Begtse, the pre-Buddhist Mongolian god of war. The red mask, decorated with beads, represents power and strength. From the Milan Klečka collection. Photo by Jakub Šedý. Image courtesy of the Náprstek MuseumCultural and scholarly professionalism increased over the decades in Czechoslovakia. Thanks to programs from the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance, Czech experts could travel, train, and work with Mongolian counterparts in cultural preservation and scientific research into earlier eras. Two periods were robust; in the 1960s and again in the 1980s, teamwork in Mongolia was productive and objects thought lost or destroyed were gradually discovered. Some of these objects are now on display.

Today, Helena Heraldova, a hidden gem among Buddhist scholars, leads the Department for China and Viet Nam, Tibet and Mongolia at the Náprstek Museum. She is a prolific researcher, writer, and curator, with decades of output on fascinating subjects, specializing in Qing dynasty material culture and textiles, as well as Tibetan and Mongolian religious painting. This brings her into the realm of dance, tantric Buddhist dance masks, and ceremonial dance robes. The danced ceremonies are entirely the same pantheon depicted in the paintings. In this exhibition, there are fine examples of tsam dance masks of Mongolia’s distinct style of modeling the mask, with fields of pearl-like surfaces. There is a gorgeousness, a power, even a wildness in these expressive masks—quintessential distillations of Mongolian culture. Mongolian tsam masks are among the largest in the Vajrayana world.

Ceremonial tsam mask of the lord of the underworld Erlig Khan, the most important character of tsam dance. In one hand he holds a stick in the shape of a human skeleton, in the other a bowl made from a human skull. From the Milan Klečka collection. Photo by Jakub Šedý. Image courtesy of the Náprstek Museum

Ceremonial tsam mask of the lord of the underworld Erlig Khan, the most important character of tsam dance. In one hand he holds a stick in the shape of a human skeleton, in the other a bowl made from a human skull. From the Milan Klečka collection. Photo by Jakub Šedý. Image courtesy of the Náprstek MuseumThe Náprstek Museum is an ethnographic museum, and continues the high ideals of a traditional research museum, with scholars conducting research based on collections. Such museums are the pride of Europe and a pleasure for any serious researcher. A culture of collecting transformed into a civic act of offering opportunities to better understand other cultures, including publishing regularly in popular literature as well as standard academic papers. The height of scholarship was put toward methodically cataloguing, preserving, and presenting objects. At the same time, new research, public symposia, and other exchanges allowed both the collections and the research using the collections, to be made available. The Náprstek’s Mongolian collection comprises 2,500 objects. The finest and most interesting of these are displayed in the new exhibition.

I was delighted when Dr. Heraldova contacted me about using a Core of Culture DVD, Lamayuru Sanctuary of Dance in the exhibition, The Secret Life of Collections: Mongolia and Buddhism. I was surprised I did not know of such a fine scholar, nor anything about the wonderful Náprstek Museum. It is a pleasure to introduce her and the museum, here. Helena Heraldova has lived an admirable life of conducting research around beautiful objects, publishing new work and creating exhibitions. It has been continual for several decades, like some great life yoga. The exhibition is open to visitors, using social distancing measures. I hope to get a chance to see it, and encourage anyone who can get there safely, to do just that.

Náprstek Museum of Asian, African and American Cultures, Prague, Czech Republic. Image courtesy of the Náprstek Museum

Náprstek Museum of Asian, African and American Cultures, Prague, Czech Republic. Image courtesy of the Náprstek MuseumThe Secret Life of Collections, Mongolia and Buddhism

Náprstek Museum of Asian, African and American Cultures, Prague

23 June–25 October 2020

See more

Náprstek Museum of Asian, African and American Cultures

Core of Culture

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Mongolia’s Hope: Baasansuren Khadsuren, the Singing Abbot of Erdene Zuu

The Blessings of White Tara Beyond Time and Space

A Reflection on the Robert Ho Symposium: Bridging the Inner and Outer Divides

A Conversation with Mongolian Yogini Kunze Chimed on Her New Book: Lujin

The Sound of Awakening: Meeting the Mongolian Yogini Kunze Chimed

Related news from Buddhistdoor Global

Asian Buddhist Conference for Peace Marks 50th Anniversary in Mongolia

Fourth International Conference of Buddhist Women Held in Mongolia

Challenges Ahead for Millennial Monks Revitalizing Mongolia’s Ancient Buddhist Tradition