In May, the Woodenfish Foundation held a conference on “Buddhism, Science, and Future” in Seattle. Among the guest speakers was James Hughes, co-founder and executive director of the Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technology (IEET), a non-profit organization that aims to address the social implications of technological advancement. Hughes also works as Associate Provost at the University of Massachusetts, Boston and is the author of many books, including Citizen Cyborg: Why Democratic Societies Must Respond To The Redesigned Human Of The Future (Westview 2004). After the conference, Buddhistdoor Global had the pleasure to sit down with Hughes and discuss his vision of the future.

I ask Hughes where it all began and he tells me that he grew up in what was an agglomeration of two churches—the Unitarian Church and the Universalists—which provided a platform for religious skeptics of the 1960s to gather in what was then a very “churchy America.” As a young boy, he was exposed to a variety of different faiths in equal ways, including Buddhism. Yet it was as a teenager that he developed an interest in Buddhist philosophy; partly because his parents’ divorce sparked existential questions in him and partly because he had access to books typical of that era in San Francisco, including literature on Hinduism and Buddhism. Realizing that he did not believe in a god, Hughes felt drawn to Buddhism. He became involved in Tibetan Empowerment and in 1979 he created a meditation group at his college. “I was also very left wing and part of a socialist group,” he explains. “Those two things were in a lot of tension to me.”

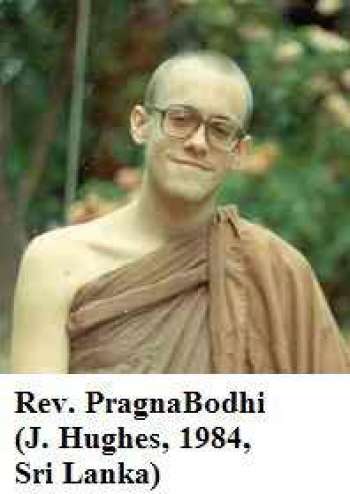

However, he adds, “There is a long-standing tradition of Buddhist social ethics, of people trying to figure out what the social ethics of Buddhism might be.” In 1983, Hughes moved to Sri Lanka to join the Sarvodaya Shramadana, a Buddhist land-reform movement that was inspired by Gandhi’s work in India. Five days after his arrival, the civil war broke out and Hughes’ “romantic beliefs” about the Buddhist country were quickly crushed. At the invitation of his hosts, Hughes temporarily ordained as a monk, but he was disillusioned by the political role that Buddhist monks played in the conflict. After writing critical papers on the topic, he escaped the country “by the skin of [his] teeth” a day before he was due to be arrested.

While he was living in Japan with his wife, Hughes became increasingly interested in bio-ethics. Having observed that Japanese and Americans view the fetus and brain death in very different ways, he realized that bio-ethics poses questions that are deeply philosophical in nature.

“What is the nature of a fetus? What do we owe a fetus?” He asks. “Does a fetus have a self or not?” He was surprised to discover that, while Japan was very tolerant when it came to abortions, the country was still debating brain death. “Brain death is also a question about self,” he explains. “If you’re never going to have a self again, are you really there anymore?”

It was around this time that Hughes began to conceive of how to combine his interests in Buddhism, politics, and bioethics—it also connected him with the transhumanist movement. “[Ever since] we were capable of symbolic thought, human beings have been able to think about what could be. We have imagined better bodies, healthier bodies, longer lives, and a better society.”

His view is that these utopian aspirations were traditionally expressed through religion and spiritual practices (such as herbs, chanting, and sweat lodges). With the advent of Western enlightenment, however, these practices gave way to the notion that science and technology would provide a superior means to enhance human life. That is, Hughes explains, until World War II happened; the rise of the Third Reich together with the mounting threat of nuclear weapons of mass destruction turned the political left of the mid-20th century into skeptics, and technology came to be viewed as having a negative effect on human society.

Image courtesy of James Hughes

Image courtesy of James Hughes“I began to see myself as a throwback to that earlier enlightenment optimism, where there wasn’t any contradiction between believing that science and technology could make things better, and believing in democracy and freedom,” Hughes explains. “Transhumanism for me is basically that enlightenment narrative of techno-optimism applied to contemporary bio-politics and contemporary biotechnology; things that we can do to the human body and brain. Radical freedom argues that we should be able to do pretty much what we want to with our bodies, our brains, and have reproductive freedom. Just like contraception gives you the freedom to control when you have children, genetic engineering gives you the option to choose what kind of children you have. That’s a kind of freedom.”

Hughes is aware that this opens up a lot of important questions, which is why he puts forward his vision of social democratic transhumanism in Citizen Cyborg. “There are certain things that society has to do to make us free. That’s the social democratic argument, that’s the basic argument,” he explains. “We have to have policy that says we want to make sure that certain kinds of beneficial enhancements will be universally available, just like how we want medicine to be universally available.”

He posits that if we are going to have genetically engineered children, the technology should be made available to all, not only the rich, adding that he is only in favor of making a technology accessible if it will benefit society. “If it’s not going to have a benefit, if it’s actually bad for people, then we ban it. Freedom does not mean everybody being allowed to do what they want, if they’re going to harm themselves or their children.”

When I ask Hughes whether his Buddhist practice has informed his politics, he shares that, in the US, people who are involved in futurism or public policy are not usually interested in the Buddhist contribution. He explains, “I do think that Buddhism provides a certain characteristic set of intellectual tools and approaches that have been very helpful. In particular, the most Buddhist thing you can say is ‘that doesn’t exist, what are you worried about, you made that up!’” He laughs, adding, “Buddhism allows one to deconstruct things and put them back together, working beyond the false binaries by which we are usually constrained.”

I ask him what we can expect for the future. “Our sense of self—the illusion of self, the Buddhist idea of our illusion of self—is very much because we are bound by our skulls right now, so far,” he explains, adding that in the 1950s and 1960s, even the best science fiction writers still imagined that the computers of the future would be as big as a room. “Now,” he looks at his watch, “This has more computer power than the Apollo spacecraft.”

“In the next 20 years we’re going to have more change than we had in the last 200 years. We can’t possibly imagine what that’s going to mean, it’s truly unimaginable.” As a futurist, he posits that the best thing one can do is have a genuine discussion about what technologies will benefit humans as a whole, and ensure they are accessible to all.