The saffron robe of a Theravada Buddhist monastic is instantly recognizable to Buddhists and non-Buddhists alike. But what is the origin, function and meaning of the design? In ancient times, the wandering ascetics and Buddhist monks did not have a proper design for their clothing. The Mahavagga of the Vinaya Pitaka explains that in the early period of the Buddhist sangha, there were only four necessities in a monk’s life: begging for alms food, rag cloth, natural lodging and medicine derived from cow urine. Accordingly, as this text mentions, the monks used pieces of rag cloth for their attire. Here, the rag cloth is referred to as pansukulacivara, the cloth used to wrap a corpse. For monks, the use of cloth was not meant for comfort, but for the minimal protection of the body and to remind themselves of the reality of personal mortality. The rag cloth was an instrument symbolizing non-attachment.

The growth of the Buddhist Order has led to many changes. The acceptance of donations of cloth for monks’ robes is one of them. The Buddha, not being an extreme promulgator or adherent to rules and regulations of an ascetic, gradually adopted such norms to accept utensils from laities as generous donations. However, being careful of the aim of the spiritual life of the Bhikkhus, he set rules so that they did not get trapped in the material world surrounding them. According to the Mahavagga, it was only twenty years after the inception of the Buddhist Sangha that the Buddha first accepted the donation of a robe from his physician, Jivaka. Jivaka, who treated the Buddha for an illness, offered him the robe, which he had received from a king. Jivaka also requested the Buddha to allow the monks to accept robes donated by lay followers. According to the text, since then, the monk’s robes donated by the laity were governed by rules, unlike when they wore pieces of discarded rag cloth, which were not governed by any rules and regulations.

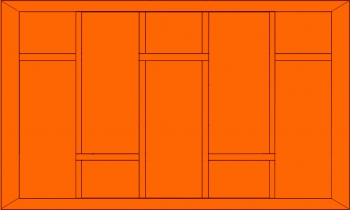

These records show that the history of the Theravada Buddhist monk’s robe goes back to the time of the Buddha, who introduced the robe with its present designed formation. A complete set of monk’s robes consists of three parts: the main robe or the outer robe, the under robe or the waistcloth, and the upper robe. Two more parts of the robe are added for the female monastic; namely, a vest and a bathing cloth. In addition, both male and female monastics use belts for the under robe. The outer robe and the under robe are made with cut pieces of cloth which cannot come from a single piece of cloth. This means that a cloth cannot be used as a robe unless it has already been previously cut into single pieces and sewn together again.

The robe, along with the gradual growth of the Sangha, also has undergone a transformation. The present design of the robe was a later addition by the Buddha. As the Mahavagga records, once when the Buddha was travelling to Dakhinagiri he saw the fields of Magadha laid out in strips, lines, embankments and squares. He asked venerable Ananda to make a design for the robe modeled after the fields of Magadha. He asked him to:

. . . can make a cross-seam . . . a short cross-seam . . a circular seam . . . a short circular seam . . . a central piece . . . side pieces . . . a neck-piece . . . a knee-piece . . . an elbow-piece; and what is cut up must be roughly darned together, suitable for recluses and not coveted by opponents. (Mahavagga, English Trans. By I.B. Horner)

Venerable Ananda did so and the Buddha accepted the design.

The robes are dyed with colors made from roots, tree bark, leaves, flowers and stalks. The monks are also allowed to accept cloth made of linen, coarse linen, cotton, silk, wool, and hemp. Besides the three parts of a complete set of robes, the monks are also allowed to have other types of cloth, to relieve itchiness, to wipe the face and for bathing. However, such types of cloth should be used only when needed.

In the Mahatanhakkhaya-sutta of the Majjhima Nikaya, Buddha admonished the monks to live contentedly with what one needs. Like the bird that flies with the weight of its two wings, so should a monk be satisfied with the monastic requisites. He instructed that a monk could have up to three robes at one time for his use, and monks possessing more than that should be dealt with according to the related rules and regulations. However, the acceptance of donations, including the donation of robes, from lay followers led the monks to have more possessions than they needed. This surplus of donations led to store rooms being set aside to place these donations. A monk was appointed as the keeper or guardian of the storerooms and also to oversee the distribution of donations to members of the Sangha.

The formation of the robe’s design in tandem with the related rules and regulations suggest that the clothing of Buddhist monks is not just a uniform, but also a meaningful instrument representing the higher spiritual life in Buddhism. Furthermore, the rules and regulations governing the monks’ usage of the robes also indicate that the Buddha had done so intentionally to guide the monks towards their aim of spiritual liberation.

Author’s note: This article is adapted from the Mahavagga of the Vinaya Pitaka.