FEATURES|THEMES|Environment and Wildlife

Touching the Earth: An Ecodharma Retreat

From rockymountainecodharmaretreatcenter.org

From rockymountainecodharmaretreatcenter.orgOn a sunny July morning a group of meditators is sitting beside a creek in the Rocky Mountains. The teacher gives instructions on paying attention to what is seen, heard, and felt, and any feelings of gratitude, joy, and love that might arise in response. On such a fine day, in such a lovely place, those feelings occur readily to most of the yogis. A day later, however, the instructions change, focusing on the damage we are doing to our planet: now the emotions that come up are more difficult: grief, guilt, fear, and anger. . . .

The ecological crisis is the greatest challenge that humanity has ever faced. It is also the greatest challenge that Buddhism has ever faced. It remains to be seen whether either will respond appropriately, but Buddhist history reveals a flexibility consistent with its emphasis on impermanence and insubstantiality. Today, a new and non-sectarian form of environmentally engaged Buddhism has begun to develop, sometimes called ecobuddhism or ecodharma. At the Rocky Mountain Ecodharma Retreat Center (RMERC) in Colorado, we are doing our best to find appropriate responses, by experimenting with a variety of retreat forms.

So what is an ecodharma retreat? How would it differ from traditional meditation retreats? The two of us, both founders and teachers at RMERC, have been developing such retreats for the past few years. We continue to refine the process, and the program this past summer was powerful and transformative. This article is an initial progress report on this new and urgently needed type of Buddhist practice.

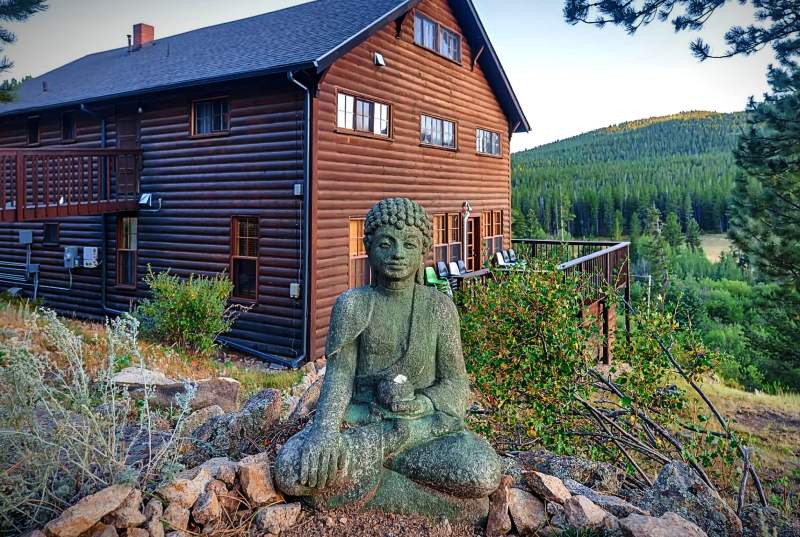

The RMERC lodge, first built in 1939 and remodeled in 2018. From rockymountainecodharmaretreatcenter.org

The RMERC lodge, first built in 1939 and remodeled in 2018. From rockymountainecodharmaretreatcenter.orgOur approach is inspired in part by Joanna Macy’s pioneering Work That Reconnects, as well as the Ecodharma Centre in Spain, and also utilizes some of Zen scholar David Loy’s book Ecodharma: Buddhist Teachings for the Ecological Crisis. Essential to the program, however, is that a group of yogis concerned about the environment practice together in a natural setting. This involves living together 24/7, which creates community and also relies on deep listening and deep sharing and being heard by others who are similarly open and vulnerable.

RMERC is an ideal location for such a retreat, being pristine and peaceful, with a wide variety of forest trails, alpine meadows, rocky crags, and a gently flowing creek. At the root of our ecological crisis is that we normally experience ourselves as separate from the natural world, which has become a collection of resources for us to exploit, rather than our home. To realize the deeper truth of our non-separation, direct contact with nature is very important. It is difficult to realize your intimacy with something—and love for it—while staying away from it.

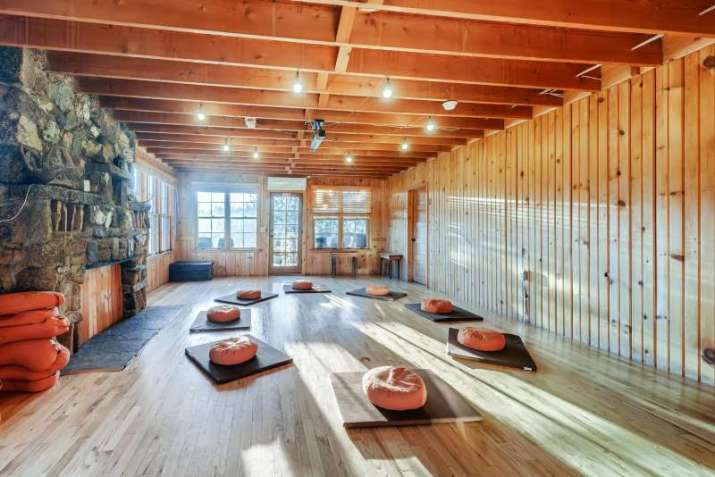

In fact, we have a good model: the Buddha himself, whose solitary meditations culminated in his awakening under a tree, next to a river. Afterwards he was challenged by Mara: “Who verifies your enlightenment?” The Buddha touched the ground he sat upon: “The Earth is my witness.”

Earth-touching Buddha. From rockymountainecodharmaretreatcenter.org

What might happen if we practiced in the way that he did? RMERC’s wild setting offers the supportive and nonjudgmental context needed to make profound transformation possible. Meditating in nature leads to increasing realization that the Earth is acting through us, as us. Empowered by something greater than ourselves, we can become part of the Earth’s immune system.

Our ecodharma retreat last summer was eight days. Fortunately, the weather stayed warm and mostly dry and we could practice outdoors as much as we wanted, which was most of the time. The daily schedule, almost all in noble silence, usually included meditation instruction, sitting meditation, hiking meditation, open practice periods, a campfire Dharma talk, and a small group breakout session for sharing and interpersonal exercises. The specific practices varied: emphasis the first morning was on sensory awareness of the natural world. Instead of looking within—for example, concentrating on the breath—the focus was on mindful hearing, seeing, and bodily sensing while walking on forest paths or sitting under trees.

On the first afternoon there was a circle in which everyone shared their hopes and intentions for the retreat. This began to build supportive relationships among the participants, which became more important as the process developed.

Dharma talks were offered in the evenings, around the camp fire. Following the example of Joanna Macy’s spiral process, the initial talk was about gratitude: that being thankful is not just something we occasionally feel, but a transformative practice to be cultivated, which nurtures the ability, willingness, and courage to work for the healing of our relationship with the natural world.

Instructions the next day supplemented bare sensory awareness with appreciation of nature. People found a spot that attracted them—maybe a tree or flower, or a rock by the creek. They quietly meditated on it and with it, perhaps touching it, expressing out loud or to themselves the positive feelings that emerged, such as affection, thankfulness, and enjoyment or joy. Attention creates connection, connection leads to caring, and caring to a simple, spontaneous form of metta practice: may this flower be well, may all of us be well together! The afternoon involved a pair exercise, with each person taking turns to repeatedly ask the other: “Tell me something you feel grateful for.”

These gratitude practices served to ground us for the difficult work that followed.

The next few days were devoted to becoming more aware of the impact of the ecological crisis, with emphasis on our personal emotional responses to that realization. The urgency of addressing global heating can distract us from the fact that the climate emergency is only the tip of an iceberg that includes many other interconnected issues, such as a species extinction event (better called an “extermination event”); toxins in the water, air, earth, and our own bodies; widespread plastic pollution; soil degradation (half of all agricultural topsoil has eroded away during the last century); radioactive contamination; overpopulation . . . the list is long.

And to all that must be added social-justice concerns regarding racism and ethnicity, neocolonialism, gender, and class, always remembering that ecological degradation is affecting some people—most of them poor and/or colored—much more than others. In sum, our now-global civilization has lost its way, and converting to renewable sources of energy, essential though that is, will not be enough to fix what has gone wrong.

It’s quite understandable that we don’t want to think about such disturbing issues, but of course that’s not the response needed. Those who sign up for an ecodharma retreat have at least some awareness of our predicament, but that does not mean they fully feel what it actually means. Most of us have repressed such feelings, to a greater or lesser extent, as a way of coping with the cognitive dissonance. Along with almost everyone else, we ignore what we know or suspect to be true, and end up living in a delusive and deadened world, each of us reinforcing the collective denial. But we can also help each other overcome that denial and get in touch with our repressed grief and other emotions.

Grief is so uncomfortable that we consciously and unconsciously flee from it. We argue about facts or strategies, or become angry at those whom we identify as responsible for the mess we’re in. We seek grounds for hope and, when hope fails us, we fall into despair—a future-preoccupied dualistic way of thinking, which evades what is happening right here and now. Ironically, despair can be a relief: if there’s no hope, there’s no need for me to do anything. But embracing despair is not the same as feeling our grief, which is much more difficult to do.

We addressed this with body-focused guided meditations that used news items, poems, personal stories, and visualizations, each clearly describing an aspect of the eco-crisis. Each reading was followed by a period of silence, with encouragements to stay in touch with what the body was feeling. Later, after meditating in nature by themselves, people shared what was happening with them in the small groups. For this process, the developing sense of community, especially interpersonal trust, became very important. The vulnerability that others showed helped each of us to open up to our own deepest feelings, leaving everyone emotionally raw.

From rockymountainecodharmaretreatcenter.org

From rockymountainecodharmaretreatcenter.orgThe climax of the retreat was a solo of a day-and-a-half, when each person went off with a tent and sleeping bag to find their own wild spot. The intention was to deepen their relationship with the Earth by grounding themselves more firmly in both the love and concern they felt, and the dark and difficult side of the destruction of which we are all a part. People found their own way to communicate with the land, plants, and animals around them. Some people fasted. A few stayed up all night, listening to what the darkness had to offer.

Afterward we rejoined and shared what had happened, often with tears or laughter—and sometimes both. The solitude helped the week’s experiences integrate in a way that became empowering, giving people a greater capacity to bear what is happening, thus enabling them to become more engaged, in mindful response to our predicament. Feeling and enduring our grief and fear can be liberative, but that is the not the end of the process. Once a deep acceptance of our emotions begins, changing how we actually live in the world becomes possible, perhaps inevitable. Our fear and grief—which arise from our love and care for the Earth—transform into commitment, our self-righteousness into generosity, and our anger into determination.

The final talks and discussions were about the ecosattva path. Ecosattvas, like all bodhisattvas, have a double practice. They continue to work on their own individual awakening, and that personal transformation works to ground their engagement with the ecological and social crises of our time. “Form is emptiness” means that nothing is lacking right now, but that perspective is incomplete without “emptiness is form:” as we let go of our egos and begin to realize our true formless nature, compassion arises and we are naturally motivated to respond. The path unfolds in different directions according to what each person feels authentically called to do.

In the context of don’t-know-mind—the mystery of not knowing what is possible—this double practice enables us to act without attachment to results. Yes, the future may look grim, but regardless of what happens, our task is to continue to do the best we can, living fully in this moment, without knowing if our efforts will make any difference whatsoever in the future. Have we already passed ecological tipping points, and civilization as we know it—perhaps even our species—is doomed? Maybe what we are doing is hospice work. We don’t know, but while that possibility is painful, it is ultimately okay. We don’t know if what we do is important, yet it’s vitally important for us to do it.

Responding appropriately right here and now is a path beyond hope and despair, but requires courage: to face what we fear, and then to act on it.

Of course, ours is not the only possible format for an ecodharma retreat, and we will undoubtedly continue to refine and improve it (next summer’s program will be 10 days). While the retreat ended with some closure, it also initiated transformational processes that continue and deepen. The internal work of personal healing and awakening supports one’s commitment to engage, which then calls forth new levels of internal growth to support it. As our actions become expressions of unconditional compassion, rather than fear of what may happen, they do not require particular outcomes to be nourishing. Yes, we want our efforts to be effective, but becoming a manifestation of love, wisdom, and generosity is its own reward—as well as our free gift to each other and to the Earth, which is not only our home but our Mother.

David Loy is an American scholar, activist, and authorized teacher in the Sanbo Zen lineage of Japanese Zen Buddhism. He is the author of numerous books on Buddhist history and philosophy as well as Buddhist approaches to the ecocrisis, including his latest work Ecodharma: Buddhist Teachings for the Ecological Crisis (Wisdom Publications 2019).

Johann Robbins is a Dharma teacher in the Insight/Vipassana tradition and is the director and president of RMERC. He has been meditating since 1974 and has completed the Spirit Rock Community Dharma Leader teacher-training program. In 2002, he founded the Impermanent Sangha, which has taught meditation in the context of backpacking, camping, canoing, and rafting.

See more

Rocky Mountain Ecodharma Retreat Center

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

What Keeps Buddhist Activists Sane?

Buddhistdoor View: The Climate Crisis and Our Collective Need to Wake Up

Wildlife on the Brink

Building a Climate Crisis Toolkit with Buddhist Wisdom

Planetary Healing: Buddhism and World Ecology

Halting the Economics of Extinction: How a Spiritual Resurgence in China Could Save the Biosphere

Related news from Buddhistdoor Global

Buddhist Teacher David Loy Briefly Detained in Denver During Climate Protests

New “Ecodharma” Retreat Center to Open in Colorado in June

Indian High Court Declares Ganges, Yamuna Rivers “Living Entities” in Effort to Push Conservation

US Congress Recognizes the Gyalwang Drukpa for Social and Environmental Activism

Buddhist Monk Matthieu Ricard: Veganism is the Key to Lasting Happiness

Buddhist Monk Highlights Need for Conservation on the Tibetan Plateau

Buddhist Monk Wins Wildlife Service Award