The very idea of an “American Buddhism” has been debated for decades among academics and practitioners. Studies of the phenomenon began in earnest in the 1970s, notably with Emma Layman’s Buddhism in America (Burnham Inc Pub 1976), Charles Prebish’s American Buddhism (Duxbury Press 1979) and Rick Fields’ How the Swans Came to the Lake (Shambhala 1981).

Since then, several studies of American Buddhism have been published, and in 2008, David McMahon’s The Making of Buddhist Modernism (Oxford University Press) added a sweeping theoretical analysis to the emergence of modernity in Asia and Western ideas and practices of Buddhism. While McMahon’s work helped us understand the broad confluences that have shaped much of Buddhism over the last 150 years, it was also clear that developments beyond modernity are continuing to alter the character of the 2,500-year-old religion.

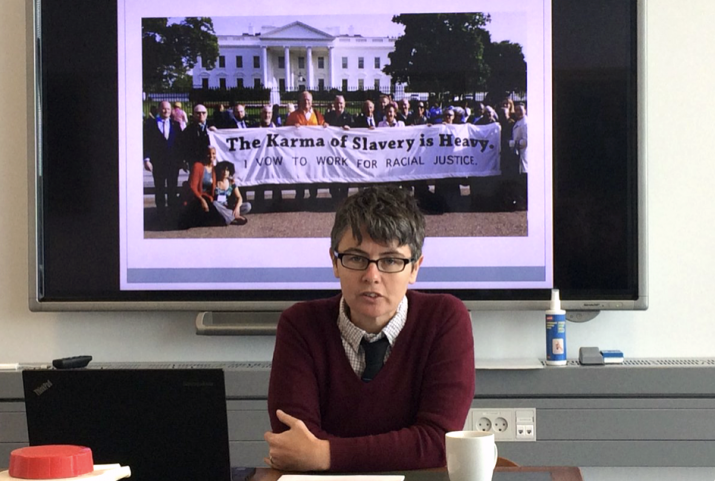

Ann Gleig’s new book American Dharma: Buddhism Beyond Modernity (Yale 2019) takes us further into contemporary and future developments in Buddhism. Gleig’s work draws from fieldwork in several influential American Buddhist communities and a rich understanding of the factors shaping a particularly American Buddhism.

I interviewed Gleig about her background, her new book, and how we can best understand this strange and ever-changing phenomenon of “American Dharma.”

Buddhistdoor Global: Can you give us a background of your academic development leading up to the start of this project?

Ann Gleig: My research is situated across two major academic fields: Buddhist studies and American religion. My background in Buddhist studies began as an undergraduate in 1992–95 at Bristol University. There I studied Theravada and Tibetan Buddhism with Rupert Gethin and Paul Williams, two of the most well-known scholars in Buddhist studies in the UK. I’m really grateful for the classical grounding I received from both of them.

When I went to Rice University in Houston, Texas, to do my PhD in 2004, my intention was to continue studying Tibetan Buddhism with Anne Klein. However, Anne’s Tibetan language class was in its third year and was too advanced for me. I didn’t get funding for a Tibetan summer school intensive, so I was really at a loss over how to proceed. Then Jeff Kripal, who was another mentor of mine at Rice, pointed out that I was really more interested in the American adaptions and assimilations of Asian religions than their classical iterations and suggested that I take the Americanist route to the material instead. So I ended up focusing on Asian religions in America, particularly what Catherine Albanese called “Metaphysical Asia,” which is one of the main lineages the “meditation-based convert communities” that this project focuses on come out of.

Ann Gleig

Ann GleigThat is quite a lot of detail, but I think it’s important to illuminate how material constraints can shape scholarly trajectories as well as the different ways in which scholars can approach Asian religions in America. I think coming to this material from an Americanist as well as Buddhist studies route gave me an increased appreciation of lived religious innovation and bricolage. Buddhist studies has tended to be a very conservative field, with many scholars privileging Asian textual forms of Buddhism and being dismissive of American Buddhism, both heritage and convert forms.

All in all, I think my hybrid academic background really served me well for this particular project.

BDG: Yes, I certainly appreciate the details here and the idea that academic careers are quite often determined by, as you say, “material constraints.” Can you say more about your involvement with Buddhism in America?

AG: Having studied and practiced Buddhism on and off for nearly 30 years now, a pressing question for me has always been: “What does it mean for me as a queer feminist woman in a (post) modern culture to be engaging with canonical texts, practices, and world views forged in a very different historical and cultural context and coming through—largely—male monastic bodies?”

So I’ve always been thinking across historical and cultural contexts in relationship to Buddhism. I think that is why Jeff Kripal encouraged me to focus on Asian religions in the American context. And, under his supervision, I wrote my PhD dissertation, Enlightenment After the Enlightenment: American Transformations of Asian Contemplative Traditions, which was a comparative project that examined the modernization of Buddhism and Hinduism, particularly non-dual lineages, across three case studies. One of these was Spirit Rock Meditation Center, in California, which is one of the two major centers of the Insight Movement. I was particularly interested in the integration of depth psychology into Buddhism that you can see in the work of teachers such as Jack Kornfield, one of the co-founders of Spirit Rock.

I defended my dissertation in 2010 and my plan was to turn it into a book but, like a lot of newly minted PhDs, I really needed a break from the dissertation, so I decided to do a couple of new ethnographic projects: one on the East Bay Meditation Center (EBMC) in Oakland, California, and one on Buddhist Geeks, an online digital project.*

On the surface, EBMC and Buddhist Geeks are two very different types of American Buddhist communities, but in my analysis of both I concluded that they demonstrated traits associated more with the postcolonial and postmodern than the modern historical period. Franz Metcalf, an editor at the Journal of Global Buddhism (JGB), who was one of the reviewers of the Buddhist Geeks article, encouraged me to extend my postmodern thesis into a book-length project.

And the result was American Dharma! (Thank you, Franz!)

BDG: In the book you write about some of the past typologies of Buddhism in America (two Buddhisms, three Buddhisms, and so on) and criticisms that have fallen on them. How can we introduce American Buddhism(s) to people if they ask—or to a beginner’s class?

AG: Yes, I think the issue is acknowledging the way the field of Buddhism in America has developed, but not reproduce problematic typologies. So I take an historic approach and trace how early scholars advanced the “two Buddhisms” typology, how that was then nuanced and extended with the “three Buddhisms,” model and then how scholars such as Wakoh Shannon Hickey problematized both typologies noting, for instance, the ways they had produced racialized hierarchies.

In introducing American Buddhism, I think perhaps the most important work to do right now is to draw attention to neglected American Buddhist communities such as the Buddhist Churches of America, Nichiren-Shu, and Sokka Gakai International (SGI). Here, I want to acknowledge and draw attention to recent articles by Funie Hsu and Scott Mitchell on Jodu Shinshu and by Myokei Caine-Barrett on Nichiren-Shu in Buddhadharma and by Jade Sasser on SGI in Tricycle.

That said, my research specialty is on what I call “meditation-based convert lineages” in my book. I simultaneously adopt and problematize both components of the term, noting that some millennial “converts” were born into convert families but aren’t converts themselves. I also argue that there is a growing awareness in these communities around over-privileging of meditation practice at the expense of other aspects of the Buddhist tradition such as ethics and community. So, essentially, I have to ask the readers to recognize the limits of these categories and hold them lightly as terms under erasure.

BDG: What, if any, seemingly new developments do think might go mainstream in the years to come?

AG: Well, in the penultimate chapter of the book, I identify three turns: a critical, collective and contextual, and I’ve been quite gratified (and relieved!) to see further evidence of these turns. For example, I attended the Soto Zen Buddhist Association (SZBA) conference in September 2018 and was struck not just by the fact that the entire conference was devoted to the theme of diversity and inclusion, but also to learn about the work being done around white privilege in Zen communities in Oregon and Minnesota. Another example is the emergence of the SF Collective Dharma in San Francisco in the wake of the dissolving of Against the Stream (ATS). Their vision statement is a perfect illustration of all three turns.

I think that we are going to see a continuation of these turns particularly around issues of racial justice and sexual misconduct/abuse and the production of more transparent and collective policies and/or the formation of more collective and transparent communities. And, more likely than not, we are also going to see the continuation of opposition to these developments.

BDG: You mention in the conclusion a number of ways American Buddhism might develop or be framed in the future. Can you think of any project or projects that you would love to see the next bright graduate student or junior academic tackle in the area of American Buddhism?

AG: I took a very broad approach in American Dharma because I wanted to illuminate patterns that were occurring across communities that might not have been apparent otherwise. But each case study/chapter in the book merits a book length treatment of its own. So I would really love to see more focused and detailed treatments of some of my chapter themes—racial justice, sexual misconduct/abuse, Gen X teachers—which confirm or refine or even refute (although hopefully not!) my findings.

In terms of the postmodern, postcolonial, and postsecular frameworks in the conclusion, I hope American Dharma functions as a foundation and springboard for junior scholars in the way David McMahan’s seminal The Making of Buddhist Modernism has for me and many others.

Because really, at the end of the day, that is what scholarship should be about: continuing the conversation and developing our understanding further as a community of scholars.

* The results of these are published as: Ann Gleig, Dharma Diversity and Deep Inclusivity at the East Bay Meditation Center: From Buddhist Modernism to Buddhist Postmodernism? Contemporary Buddhism: An Interdisciplinary Journal Vol. 15: 2 (2014) and Ann Gleig, From Buddhist Hippies to Buddhist Geeks: The Emergence of Buddhist Postmodernism? Journal of Global Buddhism Vol. 15 (2014) http://www.globalbuddhism.org/15/gleig14.pdf

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Survey of Buddhist Healing Practices in Philadelphia Publicly Available

Pioneering Himalayan Buddhism in the US: The Jacques Marchais Museum of Tibetan Art

Scholarship, Stereotypes, and Spirituality

Bringing the Dharma to the Dismal Science: The Buddhist Economics of Prof. Clair Brown

More from Western Dharma by Justin Whitaker