FEATURES|COLUMNS|Ancient Dances

Tyra Kleen: Mudra

Tyra Kleen in her studio, date and photographer unknown. From Core of Culture

Painter, illustrator, and single woman Tyra Kleen (1874–1951) was a world traveler and recognized artist of the Art Nouveau era. She found her highest expression depicting classical Indonesian dances in Bali and Java, making extraordinary paintings and lithographs of dancers. She also produced groundbreaking drawings and painted studies of mudras, or empowered ritual hand positions, an element of nearly all Asian and Himalayan dance and religious art traditions.

This intrepid Swede stood on her own name. Tyra Kleen was a wealthy turn-of-the-century aristocrat, who used her position to seek personal freedom and to express the spiritual in art.

Kleen never had children, and she staked her name as an artist by studying at the best studios in Europe and having a genuine profession as an exhibited artist. Her understanding was broad: marriage, social structure, and religion were prisons. She learned how to disguise herself as a man, wore bloomers, rode a bicycle, and traveled internationally alone, or in the company of another woman. Kleen insisted on her freedom. Her aristocratic privilege allowed it and afforded it.

During a two-year trip that began in 1919, traveling to what was then the Dutch East Indies, this self-denying, daring individual glimpsed something worth understanding in dances far from her own home. The insight reveals her curious intellect, as well as her cultured sensibilities toward foreign religious expression. She wanted to leave a lasting record of spiritual dances. It is fascinating to notice that positivist artistic records, such as made by the Charles Darwin’s team of naturalists, producing realistic, “scientific” depictions, was much in vogue and enlisted a certain type of extraordinary draughtsman. Tyra Kleen rejected this realism on principle.

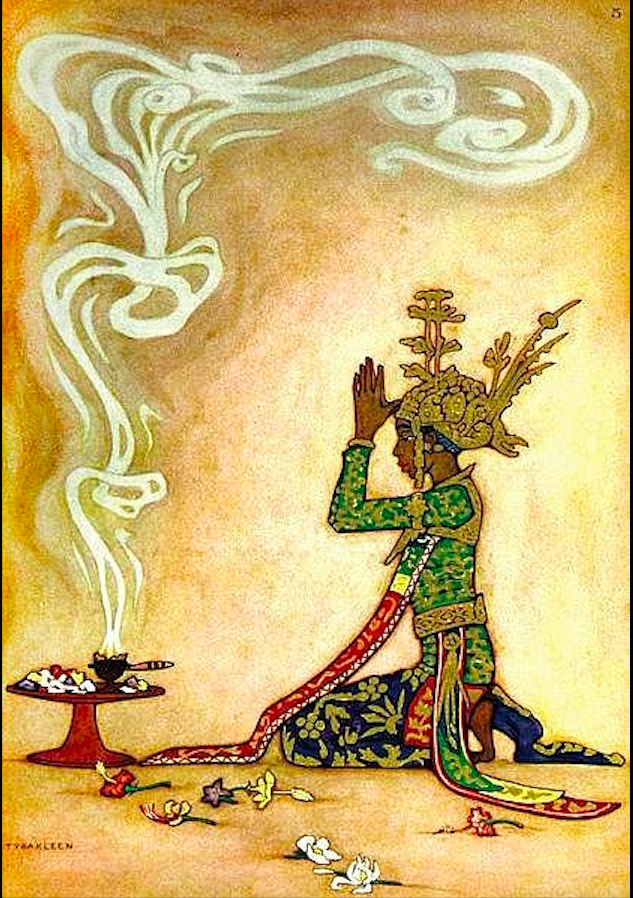

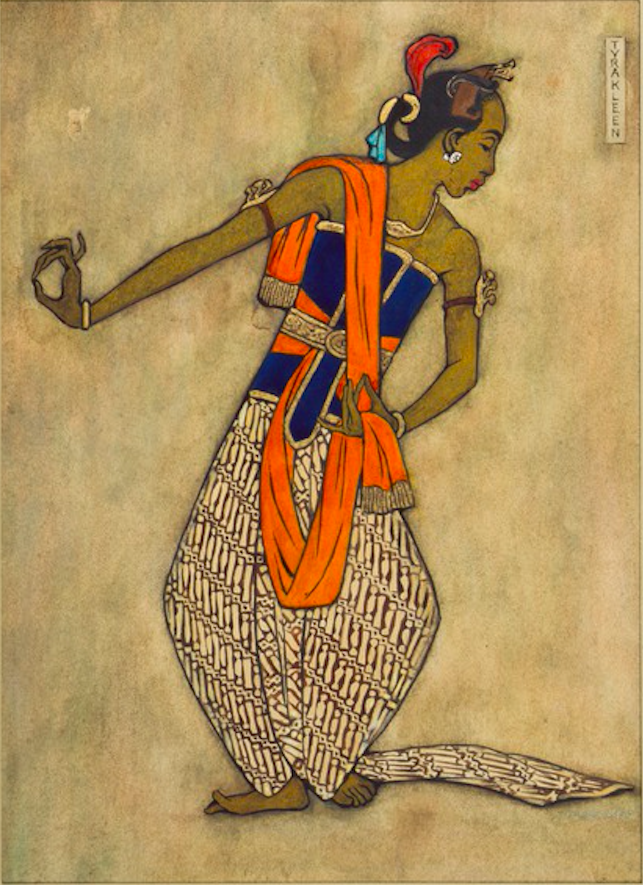

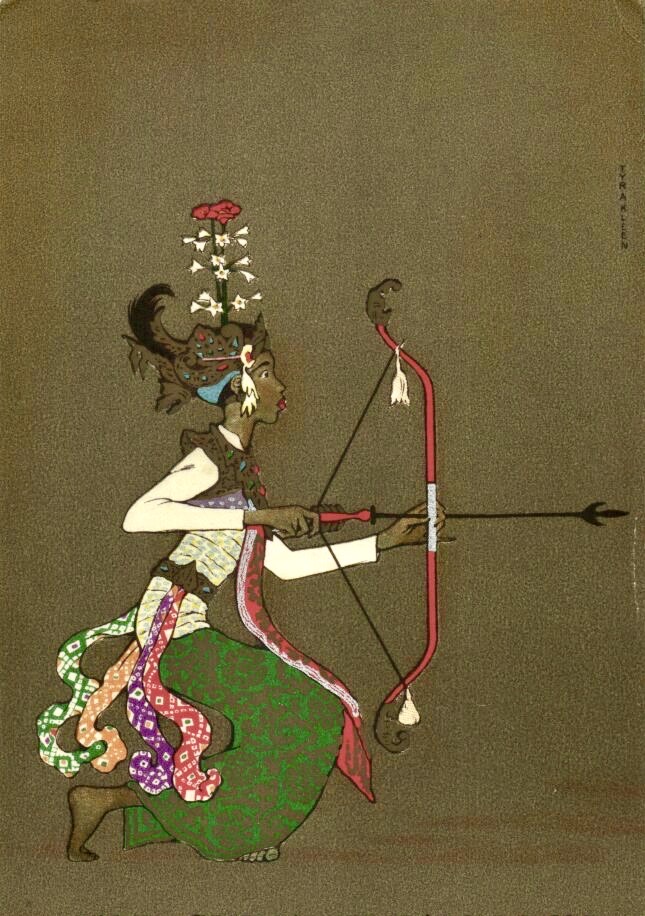

Balinese Dancer.

Lithograph by Tyra Kleen for Temple Dancers of Bali (1936).

From Core of Culture

By contrast, Tyra Kleen was a seasoned studio artist, having trained in her native Sweden, Paris, and Rome. As an illustrator of books, she moved masterfully between symbolist myth, narrative mindscapes, and Art Nouveau’s sheer delight in exquisite design. She expected her subjects to sit for paintings. Her work is as finished and beautiful as a fine craftsman’s. For all her apparently modern behavior, she was a creature of a former time, reflecting symbolist art and theosophy. Her aesthetic is integral to her documentation of the Indonesian islands; part of her method.

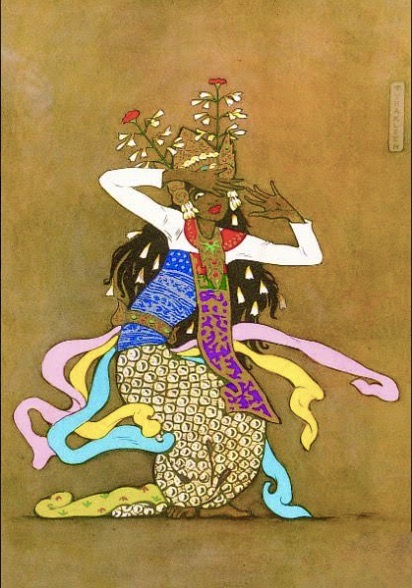

Balinese Legong Dancer, by Tyra Kleen

for Temple Dances of Bali (1936). From Core of Culture

But her subjects didn’t always stick around for the painting sessions. Some of the Balinese royal dancers had no idea was she was going on about, a white woman asking to see sequences and gestures again and again. Having Tyra herself change a position or angle to assist her painting, having them stand still in poses . . . some of them simply stopped coming to her studio and stayed at the palace. She was determined and knew the painstaking process of her own methods. One aspect of the excellence of her records is their consistency.

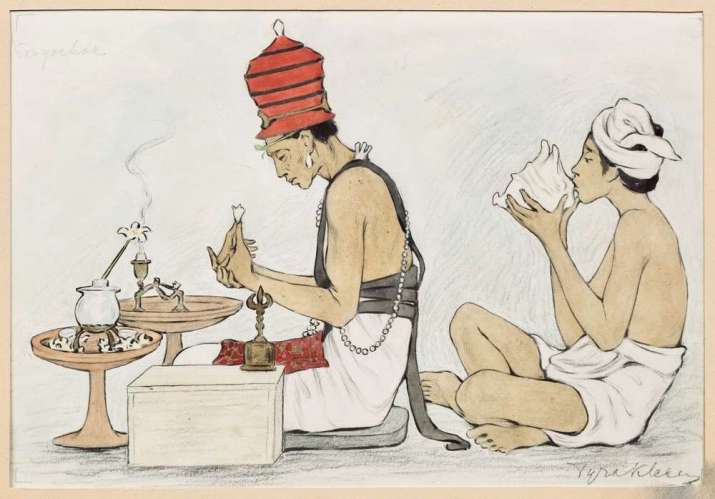

Kleen had tried to record mudras—such as she had witnessed in dances and rituals, and subsequently succeeded in having priests model for her the mudras, body postures, and implement use. But the local desire for secrecy prevailed in that these village priests intentionally mis-performed the mudras and wore their garments incorrectly.

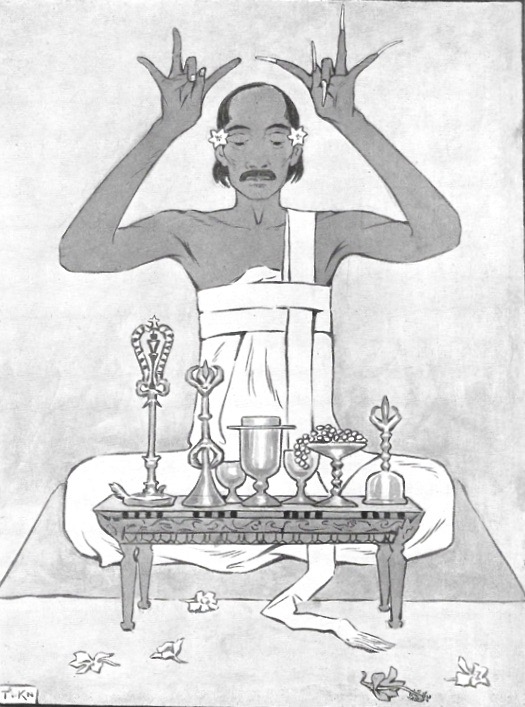

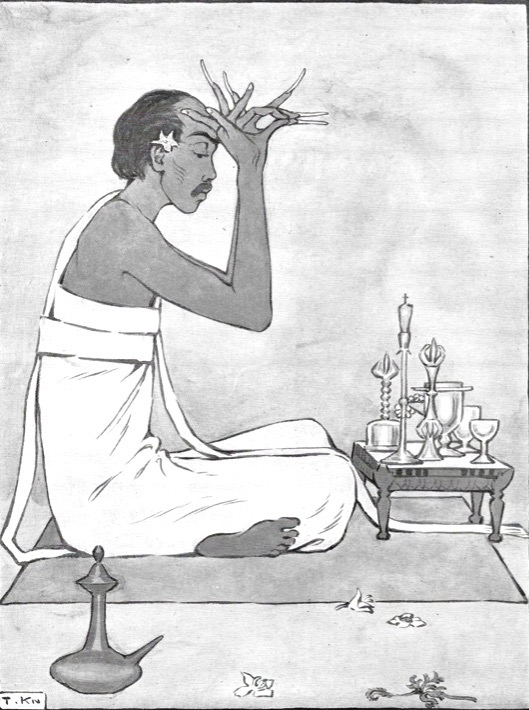

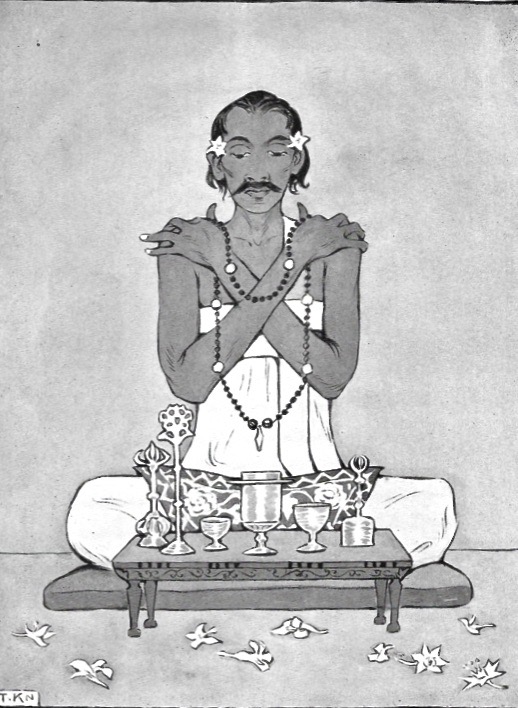

Balinese Buddhist priest performing Vajraraksha Mudra, front and

side views, by Tyra Kleen for Mudras, The Ritual Hand-poses

of the Buddha Priests and Shiva Priests of Bali (1924).

From Core of Culture

This act of “teaching the wrong dance, or the dance wrong” is well known in cultures with ancient rites as a way to retain initiate behavior and to keep sacred dances secret. A Bhutanese village once mis-performed for a UNESCO documentation—not for secrecy, but in response to the misappropriation of funds and for taking credit for “saving” their dance. To the Balinese locals’ great surprise, Kleen found them out by comparing what they had performed and how they wore their robes with her own earlier onsite studies of other areas of Bali.

Fortunately, Kleen’s aristocratic contacts brought her into the circle of Gusti Bagus Jelantic, the raja of Bali. He personally arranged for Kleen to stay in a village removed from other posts of civilization, in Sideman, and there with authoritative exponents and a creative environment in which she knew how to be productive, Kleen produced her great work. By this time too, she had learned better how to win the confidence of the Buddhist and Hindu priests. She did this in part by sharing material information regarding Catholic ritual, which the tantric priests saw as similar in ways to their own.

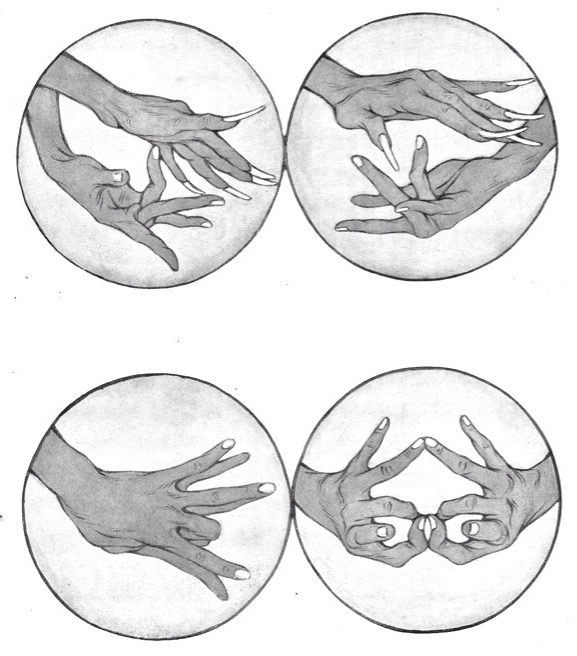

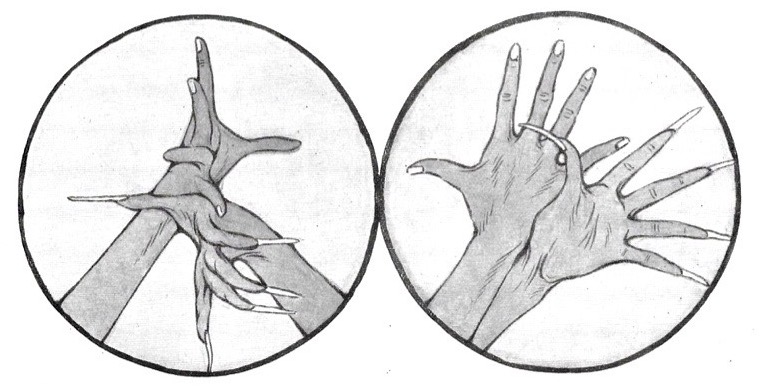

Four distinct mudras, by Tyra Kleen for Mudras, The Ritual Hand-poses

of the Buddha Priests and Shiva Priests of Bali (1924).

From Core of Culture

Tyra Kleen had a keen eye for dance, rooted in an artistic impulse toward the line of movement in all things. Her social connections finally allowed her to attend royal performances in Bali and Java, where she lived for two years, from 1919–21, many years after her first Parisian solo exhibition in 1896. She was a mature artist when she worked in Indonesia.

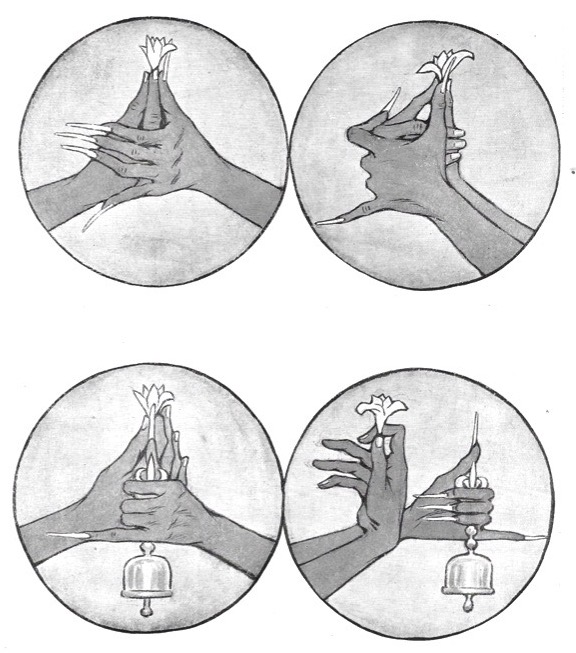

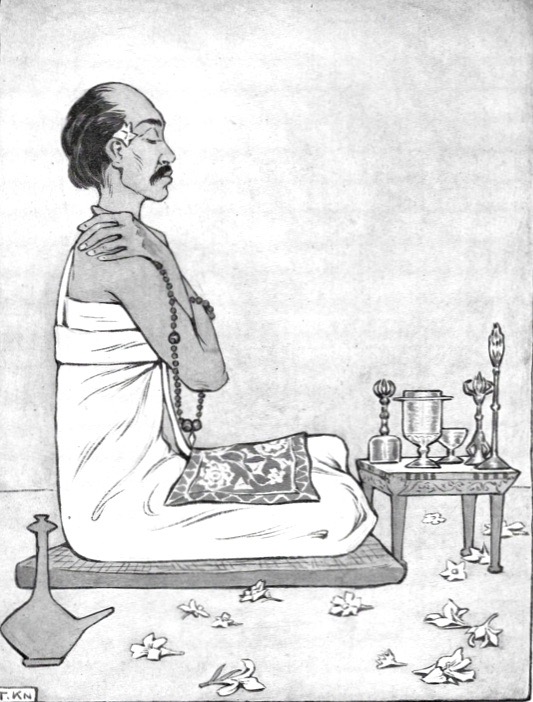

Four mudras with implements and flowers. Kleen noted that one cultural

distinction of mudra performance in Bali and Java was the inclusion

of flowers. A single blossom is added to the mudra and when the mudras

change, the blossom is flicked to the floor and another taken up, resulting

as well in an offering of flowers. By Tyra Kleen for Mudras, The

Ritual Hand-poses of the Buddhist and Hindu Priests of Bali (1924).

From Core of Culture

Even the captivating and mostly imaginary Oriental dances of Mata Hari performing in Paris influenced Tyra Kleen, who was indignant after she traveled to Indonesia and realized in the process that Mata Hari’s dancing was utterly bogus. This sharpened her dance eye. Her love of the esoteric required accuracy of form, symbol, and movement. She brought this symbolist rigor to her depictions of Balinese and Javanese dancers. Cultural accuracy was one purpose of her artwork.

Mata Hari (Margaretha Geertruida Zelle), as known for her spy work as her dancing and nudity, generated serious academic and cultural interest in Asian dances, despite her making most of it up. This infuriated Kleen. C. 1917, photographer unknown. From Core of Culture

Mata Hari (Margaretha Geertruida Zelle), as known for her spy work as her dancing and nudity, generated serious academic and cultural interest in Asian dances, despite her making most of it up. This infuriated Kleen. C. 1917, photographer unknown. From Core of CultureDance and place go together. Dance and aristocracy go together. Exotic meant far away, unimagined. It was mutual. Bali and Java were far from Sweden and little known. Of course the European aristocrats wanted to observe Indonesian royal life, which was replete with dance. This is plain human curiosity. The Indonesian dancers whom they encountered saw the white Swedish foreigner to be just as exotic.

Self portrait with a Hat, by Tyra Kleen, 1909.

Image courtesy of Thielska Galleriet

Exotic here is meant in its original, positive, and appreciative mutual sense: from a distant place. Kleen’s artwork reveres the sense of exoticism of Balinese dance and ritual mudra. It all was so unlike the society of Europe that constrained her. She was inclined to it, possessed of a special empathy. Her ability to see and understand dance was a universal and transcultural aspect of her being.

The lithographs and drawings are nevertheless rigorous documentations, possible only in the hands of a seasoned draughtsman, skillful in depicting dance. Kleen provided an insider’s perspective we are fortunate to have. Her work has been public barely 20 years. When she died in 1951, she determined that her artwork be sealed for 50 years. It was released publicly only in 2001.

Kleen also took photos worth studying and enjoying. Her choices when not to use photography, but to use painting and drawing and lithography to capture the elusive dances and mudra indicates that she believed something unique could be conveyed this way; expressed well in art. Kleen was, in fact, pre-modern in her sensibilities. The refinement of her contribution to the documentation of Asian dances reflects the general excellence with which she led her life. It makes her feminine independence all the more admirable and worth scrutiny on its own terms.

Her close interactions with, and observance of, royal dances and later, Hindu and Buddhist tantric rituals, produced three of the most extraordinary documentations of Asian dance ever produced, of a quality and type that can be compared with the famous Bugaku portfolios given by the emperor of Japan to the parents of modern dance, Ted Shawn and Ruth St. Denis, in 1926, now part of the Jerome Robbins Dance Division of the New York Public Library.

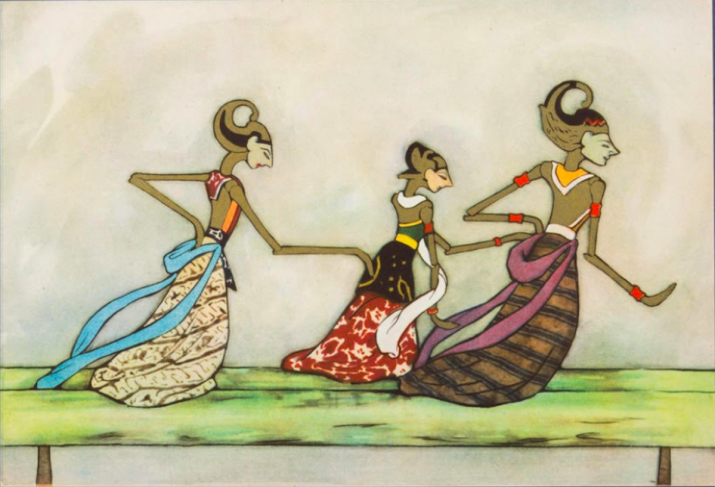

Wayang Dancer, by Tyra Kleen for The Serimpi Book, a portfolio

of 25 loose-plate watercolor images of royal dancers

from the court of Surakarta. From Core of Culture

Kleen’s Temple Dances of Bali (1936) is a portfolio of stunning lithographs of Balinese temple dancers. It can be paired with her Wayang, Javanese Theatre (1937). They are at once a full-flower expression of her mature style and period artistry, as well as intricate, accurate depictions of fabric, implements, hairstyles, and above all, movement—particularly the ritual hand movement called mudra. A third great work in her output is titled Mudras: The Ritual Hand-poses of the Buddhist Priests and Shiva Priests of Bali (1924), and is a drawn and painted portfolio of more than 150 different ritual hand positions, an unprecedented accomplishment in the ethnography of religion.

Until her study, there was little in the West beginning to decipher the ceremonial use of ritual hand gestures such as depicted in all Hindu, Buddhist, and Tantric art, save a single volume at the Museum Guimet treating Japanese Shingon Buddhist ritual mudra. There were no comparative studies of performed mudra across the Buddhist-Hindu spectrum, or comparing Buddhist tantric rituals in different cultural expressions.

Four distinct mudras, by Tyra Kleen for Mudras, The Ritual Hand-poses

of the Buddha Priests and Shiva Priests of Bali (1924).

From Core of Culture

Phases of mudra use, such as their depiction in wall paintings and sculptures, were known. Buddhist practice and ceremonial function were ignored, even more so the psychophysical aspects of mudra-as-asana. Kleen’s documentation of mudra now provides another comparison: that of the continuity of Buddhist and Hindu ritual practice over a century’s passing.

The full and complex cultural implications of archaic maritime trade patterns are still being explored. They influenced religious and inter-cultural expression. Tantric Buddhist monuments featuring elements originating in Swat and Gandhara remain on remote South Pacific Hindu islands. Hindu dance plays continue in Muslim villages in Java. Tantric Hindu mudras were likely brought to Indonesia by Saka clan workers migrating to Bali and Java, in the first century BCE and again in the sixth century CE. How the sophistication of local and imported mysticism established ritual forms remains something of a mystery, despite excellent contemporary scholarship by authors such as Peter Levenda. One most interesting and debated event is the 12-year stay in Java by Buddhist tantric master Atisha, and the ensuing idea that Atisha brought tantric forms from Java to seed in the 11th century Tibetan world.

Tantric rituals: mantras, mudras, and mandalas, traveled to Java before the eighth century, and to Japan in the ninth. This is extraordinary and overlooked. It was only in the eighth century that Padmasambhava introduced Tantric Buddhism to Tibet. Trans-verbal mudras led the way, and left their mark on gestural ritual and artistic form forever.

Buddhist priest performing mudra with rosary, front and side views.

Notice the flowers scattered on the ground. By Tyra Kleen for

Mudras, The Ritual Hand-poses of the Buddha Priests

and Shiva Priests of Bali (1924). From Core of Culture

The Muslim invasion of Java in the late 15th century caused the high caste Buddhist and Hindu priests to flee to Bali, where their descendants remain to this day. Buddhism and Hinduism have lived side by side since that time, and it was in Bali that Kleen made her unprecedented documentations of mudra, both Buddhist and Hindu. In particular, Kleen featured the mudras involved with consecrating ritual implements, and in this she records the Buddhist bells, vajras, rosaries, and vases known throughout the Buddhist world. The cultural variations Bali brought to the implements are clear to see.

This relationship of mudra and the ritual cult implement of the vajra, or thunderbolt or scepter-club, is indicative of a connection to the early Yogachara school of Buddhism. Guru Rinpoche introduced Yogachara into Tibet in the eighth century, and it is then that mudra and the vajra were apparently introduced to Tibet. The spread of Buddhist mudra-vajra-mandala can be traced from India through Nepal, Tibet, Central Asia, and China, and over the seas to Japan, Java, Bali, and coastal areas.

Balinese Priest and Attendant, by Tyra Kleen. The vajra becomes the handle for a bell integrating both implements in this setting. Mudras, The Ritual Hand-poses of the Buddhist and Hindu Priests of Bali (1924). From Core of Culture

Balinese Priest and Attendant, by Tyra Kleen. The vajra becomes the handle for a bell integrating both implements in this setting. Mudras, The Ritual Hand-poses of the Buddhist and Hindu Priests of Bali (1924). From Core of CultureIn Java, the great stupa of Borobudur is engraved with sculptures and reliefs on every level, depicting mudras in a variety of settings, lay, ritual, and deific. Mudras are code. Nonetheless, the monumental Borobudur mandala is enigmatic. Mudras are derived from magical societies, and connect with the origins of Tantra—the great and ancient techniques of enlightenment through the complete appreciation of life, rather than a rejection of it. Borobudur is an explosive celebration on the landscape, replete with ritual mudras.

The great tantric mandala monument at Borobudur in Java, eighth century. From Core of Culture

The great tantric mandala monument at Borobudur in Java, eighth century. From Core of Culture

A flying yogini, or apsara, performing mudra, in relief.

Borobudur, ninth century.

Image courtesy of Carmen Mensick

The precise hand positions of mudras are the physical representation of mantra, empowered chanted sounds, as a formula. Mudras are formulae in Tantra. Transcending spoken language, mudras crossed the spiritual landscape, seascape, and mindscape. They absorbed Hindu, Tantric, and Buddhist meanings. They coupled with the use of wizardly implements such as thunderbolts and daggers. They were adopted and incorporated into dance and tantric rites, developed from their earliest known use as a means of dramatic danced Vedic storytelling.

This way, esoteric, secret techniques of the mind were preserved and transmitted in three ways: called to mind as visualization, intoned to summon, embodied in mudras. A spell, a formula, an effective agent can be a drawing, a sound, a gesture itself. Mudra hand gestures created an unspoken esoteric language of mind; a kind of occult sign language, at once indicating information and embodying energetic transfer. Mudra means “fire,” mudra means “seal,” as part of a process that involved mantra as a formula. The hands and fingers can be used like an abacus to do complex mathematics. This act was also called mudra.

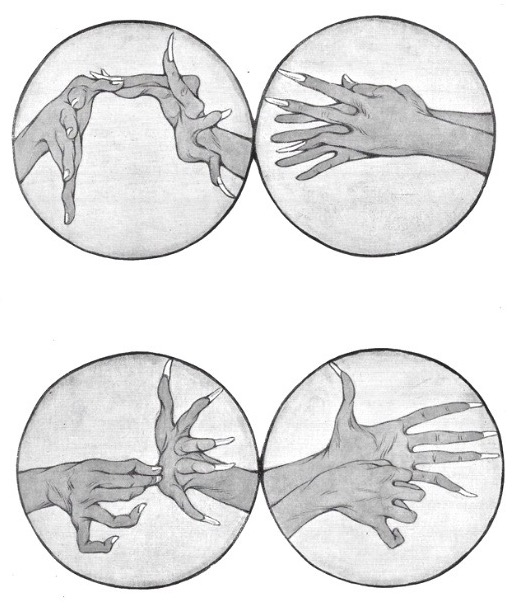

Two distinct Buddhist mudras, by Tyra Kleen for Mudras, The Ritual

Hand-poses of the Buddha Priests and Shiva Priests of Bali (1924).

From Core of Culture

A. J. D. Campbell writes in his introduction to Kleen’s book, Mudras:

The mudra illustrate visibly and materially a formula. The formula or mantra is composed of short extracts from the Vedas; of the names of spiritual Powers, benevolent and hostile, preceded and terminated by ‘words of power’, or, lastly, a series of unmeaning syllables, so selected and related that, when rapidly repeated in the prescribed manner, they set up definite vibrations in the body and the brain, producing well-defined and calculated states of consciousness.

The mantric sounds were chanted Sanskrit letters. The empowered letters have divine properties. The simulation of the letters through the interlacement of the fingers as mudra, concentrated all the implications into a psychophysical act, thereby acting as a “seal” to the metaphysical content being transmitted. Mudras in ceremonies and tantric visualization also imitate the mudras of various deities, similarly acting like a lightening rod, attracting at once the divine attributes of a given deity. Mudras are magic, in their ability to attract and focus energy.

Ritual is composed of intentional elements. There are no extraneous movements in a ritual. Mudras are intentional, directed, and efficient. It is not so much, as art historians and intellectuals would have it, frozen: that this mudra symbolizes this deity or that intellectual concept. In tantric ritual, ceremonial mudras flow in sequence like a dance, and their cumulative experience is the point, much like a dance is understood as a whole, not a set of discreet one-on-one correspondences with movement acts. Yes, there are many correspondences. Mudras have inherent psychophysical power, just as dance does. Ritual mudras are a dance of the hands.

Javanese Hand Puppets, by Tyra Kleen for Wayang, Javanese Theatre (1937). From Core of Culture

Javanese Hand Puppets, by Tyra Kleen for Wayang, Javanese Theatre (1937). From Core of CultureIn the evolution of tantric mudras, once their ritual use abandoned strict correspondence to Sanskrit letters, they became a sophisticated secret language among esoteric initiates, crossing spoken languages and cultures, and taking on ever more abstruse mental capacities. These cultural expressions, like the evolution of genetic variations, are of great interest. The performance of mudras is an ancient living practice, unceasing since its origin more than 2,000 years ago. Tracing the consciousness-altering functions of mudras is not unlike tracing a martial arts tradition of body-mind. These transmissions are shrouded in secrecy, manifesting as forms.

The linguistic jungles, mountains, and oceans that connected India to the Himalaya, China, and the South Pacific were prone to modify the aural nature of the mantra, thus modifying their innate power as well as their inherent actual spiritual idea.

The mudra remained as a kind of esoteric lingua-franca, transcending language and highlighting the psychophysical reality of transmissions. For this and other reasons, mudras become a baseline for comparison between sets of transmitted mantra and also variations in transmitted ritual mudras.

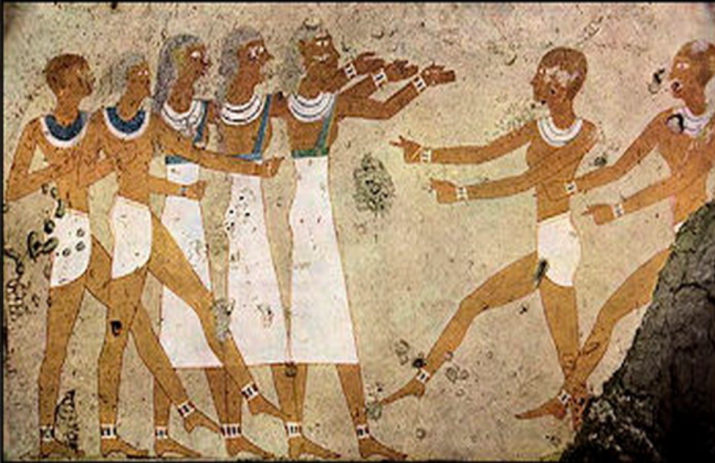

Societies and kingdoms collapse. Mudra continues. Languages change, mudras stay the same. Kleen’s work becomes more important over time. Where there is language, there is pre-language, and this reality highlights the profound significance of dance and mudra in the study of Buddhism. The language of gesture is probably the oldest language in the world, and the most naturally universal. There is no doubt, based on Aztec, Egyptian, Chinese, and Greek records, that hand gestures played a great role in the most ancient rituals.

Hand gestures in Egyptian dynastic dance. Wall painting, pyramid, Egypt, pre-2000 BCE. From Core of Culture.

Hand gestures in Egyptian dynastic dance. Wall painting, pyramid, Egypt, pre-2000 BCE. From Core of Culture.It is worth noting that Kleen had very long fingers and toes; she had to have her gloves and shoes custom made. She was an expert draughtsman as evidenced by the clarity of the complex mudras she depicted. She drew Buddhist priests enacting mudras with very long fingers. This makes the enfoldings easier to see, and is an extraordinary arch-stylization.

It was difficult enough to have access to a royal dancer or priest, as a single foreign woman—in her painting studio—but to attempt to draw the accurate and authentic shapes of the various complex mudras, among the most intricate aspects of the dance and ritual, launches her effort into a rarified ambition.

Kleen succeeded famously. Mudras was shown as an exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London in 1923 and published soon after as a book, with an introduction by A. J. D Campbell, who praises her for opening a new field of study. This book showcases her mastery of symbolism and idealism, and is a testament to her surety of line.

Kleen wanted to depict what could not be quantified, but she despised the fraud of Mata Hari’s “Orient.” Her result is clear and striking, and experiencing a renaissance in appreciation. Tyra Kleen was awarded the Johan Axel Wahlberg Medal in 1938, given to the person who most furthered anthropological and geographical science through outstanding work. That same year, young Swedish art collector Rolf De Mare lead his dance documentation team to Indonesia, including celebrated anthropologist Claire Holt, where Tyra Kleen had been 17 years earlier.

Of an epoch featuring original cross-cultural dance encounters, Kleen’s early and brilliant work in Indonesia, joins Ted Shawn’s. They share a combination of entrepreneurship, expeditionary vision, and artistic expertise. Ted Shawn was able to achieve rare documentations of ancient Asian dances, including Buddhist Cham. He filmed during his trip through Asia in 1925 and 1926, which was less methodical that Kleen, an offshoot of a performance tour. Film and photographic technology expanded greatly between 1925 and 1938, when DeMare followed in Kleen’s footsteps.

Artist Tyra Kleen touched ancient Asian dances firsthand. She saw that dance had an integral role in spiritual life, unlike in the West. She honored this. From the hardships of expeditionary travel and its noble intention, come the sublimities of discovery and new realms of human respect. The best of her times, this Swedish adventurer leaves us with beautiful records of her encounters, and more than that at the same time, give cause to reflect on the high-mindedness of cultural behavior and its lasting result.

Balinese Dancer, by Tyra Kleen, 1937.

From Core of Culture

With special thanks to Dr Elisabet Lind, Museum of Ethnography, Stockholm.

See more

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Ted Shawn on Buddhism

Performative Iconography, Part One

Performative Iconography, Part Two