FEATURES|COLUMNS|Ancient Dances

When Dance Transforms

Black Hat dancer in a photo shoot with Herbert Migdoll, Yungdrung Choeling Dzong, Bhutan, 2006. From Core of Culture

Black Hat dancer in a photo shoot with Herbert Migdoll, Yungdrung Choeling Dzong, Bhutan, 2006. From Core of CultureDance is the most ephemeral of the arts. Capturing the art of movement in a still photograph is an art in itself. To represent the spiritual essence of dance requires a kind of practice, an openness to change. Tantric Buddhist deities, such as Vajravarahi, are often depicted in poses that are physically impossible to hold, shown “mid-dance” as they move from one position to another. The idea, in part, is to show the divinity of the manifestation by depicting them in a pose that is almost superhuman.

Vajravarahi. Tibet, 14th century, gilt bronze with turquoise inlay.

Leonard C. Hanna, Jr. Fund 1982.50. The Cleveland Museum of Art.

From clevelandart.org

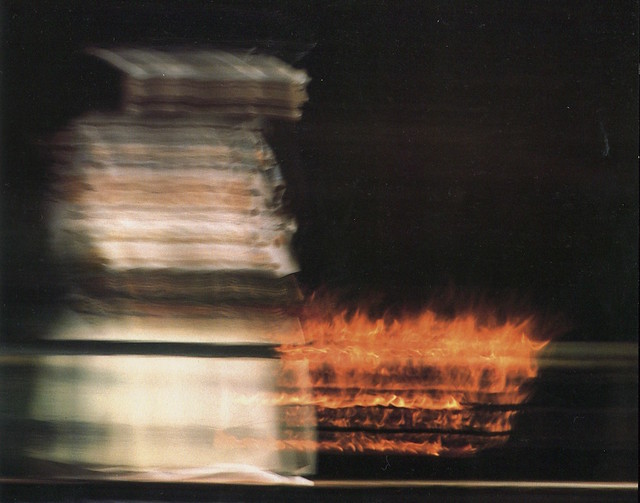

Sometimes, a photographer will seek to portray the supramundane energy within the dance, and so take a less conventional photo in order to realize the impression they are trying to make. In this photo of Takigi Noh—performances by torchlight—the photographer, Tanaka Katsumi, used time-lapse photography to capture the combined atmosphere of dancer in the night lit by flames.

The Noh play Tamura. Photo by Tanaka Katsumi. After Takigi Noh, Graphic-Sha Publishing Company,

Tokyo, 1987, p. 23

In 2006, as part of The Dragon’s Gift project sponsored by the Honolulu Academy of Arts, which explored the art and dance of Bhutan, Core of Culture, the non-profit organization I direct, was given the opportunity to create an “East-West” dance experience: a gesture to show the coming together of the dance worlds East and West. This was already happening by the very nature of the analytical method we were using to record and document the Bhutanese dances, but there was a desire to produce an artistic coupling of the spirit of dance in both.

We therefore went a step further, and invited one of the most famous ballet photographers, Herbert Migdoll, to come to Bhutan and photograph the excellent Cham dancers at Yungdrung Choeling Dzong in Trongsa. Migdoll has worked as the special projects director for the Joffrey Ballet in Chicago for more than 30 years. His ballet portraiture is iconic, with images gracing the covers of countless dance magazines. He works now as a multi-media artist, and is primarily a creator of large-scale public art (see the video below).

Bringing a world-class dance photographer and revolutionary public art creator to a remote region where even electricity is sometimes rare is not without challenges. Most of these are not technological, but have to do with forging a connection between the mind of the photographer and the minds of the dancers so that they can work together. Most of the dancers had never had their photograph taken in any way; had never seen a photograph of themselves. Imagine their astonishment when they saw themselves as the flying wizards Migdoll portrayed them to be.

Migdoll—as experienced a dance observer as ever was—had never experienced anything like the Cham at Yungdrung Choeling Dzong. It seemed authentic to him in a way that theatrical dancing no longer did. Each movement of the dancers’ bodies had clarity of its own within the vortex of the dance. As an artist, he wanted to convey something beyond the glorious form, which in the West is the primary focus. He wanted to transmit something of the power underlying the dances—the invisible strength of the danced ritual—which has lasted even longer than the stone “Mani Walls”* dotting the Bhutanese countryside.

And so he thought: Why not make a sculpture—a Mani Wall of dancers? How would it be constructed? What would be the elements? He had taken photographs of the dancers in both Back Hat costumes and the animal-headed costumes of Pema Lingpa’s revealed dance, Nga Ging, and decided to make one wall face of Black Hat dancers and the other of the Nga Ging, each wall measuring 3 meters by 6. He would over-paint the Nga Ging face with bold strokes of colorful chaotic connecting energy coming from the dancers’ plaits, and apply silver paint to the mirrors within the Black Hats’ peacock feathers.

The images you see are not photographs that have been cut up. Each section is rather a separate photograph, thus capturing the movement of the dancer through time. From the top of the head to the bottom of the dancing feet, Migdoll has divided time and bodies into nine sections. From top to bottom, each photograph captures a different moment of the dancer’s dancing. Taken as a column, the photographs depict a rare vision of moving dance in still photography.

Mani Wall, Nga Ging face. Multi-media work by Herbert Migdoll, 2007. From Core of Culture

Mani Wall, Nga Ging face. Multi-media work by Herbert Migdoll, 2007. From Core of Culture Mani Wall, Black Hat face. Multi-media work by Herbert Migdoll, 2007. From Core of Culture

Mani Wall, Black Hat face. Multi-media work by Herbert Migdoll, 2007. From Core of Culture The Mani Wall on display at the Honolulu Academy of Arts, 2008. From Core of Culture

The Mani Wall on display at the Honolulu Academy of Arts, 2008. From Core of CultureMigdoll had this to say about his time in the Himalaya: “My Bhutan experience was totally mesmerizing. My stone room—no furniture, just straw mats and a single small high pink violet window—set me on the road to the beauty of nothing as something to be strongly desired. You are gently moved into the arena of the mind instead of stuff.

“Instantly I was thinking about how to form a creative concept to document the dancers, but more importantly, to reveal their essences as spiritually oriented men of Bhutan.

“It was actually very simple. I just had to watch these dancers, both farmers [Animals] and monks [Black Hats], and reveal that dance for them is like breathing. They simply manifest it from their connection to their desire to enhance and deify their human presence. They made it simple and urgent for me to simply not get in the way of letting it happen, and so it did.

“The first encounter was the most amazing, as the palace courtyard was covered with a dry desert of packed tan earth. Once the Animals and Black Hats got going . . . [the] glaring sunlight created flashing lights from the metallic mirrors on top of their black hats and made everything disappear in the pounding of the dust [beneath their feet].

“And swirling motion. I was photographing nothing but shades of thick beige dust. I understood how mesmerizing nothing can be. I should have taken more photos of the visual emptiness, in contrast to the opulent and dazzling costumes. Nothing . . . became bizarrely more tantalizing than anything else, combined with moments of silence.” (personal communication with the author)

Seeing the museum-goers in Honolulu circumambulating the Mani Wall, taking in the materialized dance with their own movement, Migdoll felt he was making a closer connection of worlds, East and West. Moving into multi-media also meant that expectations and distinctions were challenged, and required a multi-dimensional and new response from observers. He was growing as an artist, mastering both sculpture and painting, and developing his own sense of spirituality. He was chasing the elusive dance.

Dancing Deities: Blackhats. Muti-media work by Herbert Migdoll, 2014. From Core of Culture

Dancing Deities: Blackhats. Muti-media work by Herbert Migdoll, 2014. From Core of CultureThe years passed, and Migdoll was haunted by the spiritual power emanating from the gyroscopic dancers. In fact, it was his lingering impression of the dances, however exotic and visually spectacular they may have been. How could he show the superabundance, the all-pervasive, scintillating energy that the dancers embodied and displayed?

Migdoll returned to paint. Preparing a surface, he added the photographic elements of the Black Hats. Then, wearing a gas mask against the fumes, he threw silver paint on the surface and over-painted the object, a spontaneous expression of his re-lived experience. Dance was the context; spiritual energy had become the subject; multi-media was the means. Spiritual energy blazing forth from the mirrors of the Mind.

Of his new painting, Migdoll says: “Words get in the way—you had to be there. Breathtaking, in a word. My new painting, Dancing Deities: Blackhats, attempts to manifest something that can mostly exist in the mind, this being their dancing presence and their obliteration conjoined into a work of art attempting to recreate that indescribable magic underlining the spirit of Bhutanese dance—still alive and well and amazing to see!” (personal communication with the author)

Buddhism has always attracted artists, challenged them to attempt new types of artistic expression, and embraced the use of new media. It uses art to reach the world as well as to enlighten the practitioner. Asked to act as a ballet photographer, Herbert Migdoll came to Bhutan and returned an essence-seeking multi-media artist: natural, spontaneous, spiritually enlivening—just like the dances he so admires.

* Mani walls are free-standing walls made up of carved stones, many engraved with the mantra Om Mani Padme Hum—the mantra of Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva of compassion.

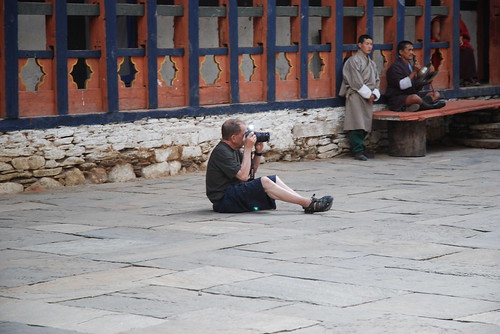

Meditation posture for a working artist. Herbert Migdoll at Yungdrung Choeling

Dzong, Bhutan, 2006. From Core of Culture

Herbert Migdoll painting and installing a public art work, Swimmer 300, 2010