FEATURES|COLUMNS|Ancient Dances

Wisteria Maiden in a Rock Garden

Go Go, or 55. Urban Guild, Kyoto. 2013. The title is a pun on

the Japanese word for the number five, go. This performance

was in honor of Heidi Durning’s 55th birthday.

Photo by Richard Silver

“Am I Buddhist?” replied dancer Heidi Durning, also known as Fujima Kanso-o, her professional name in Japanese classical dance, Nihon Buyo. “I was raised in Japan by a Japanese mother and a Swiss Father. Like many Japanese, I am Shinto, Christian, and Buddhist. Is that OK?” I assured her it was OK by me. In fact there is a popular saying in Japan: “Japanese are born Shinto, married Christian, and die Buddhist.” It is common throughout Asia that sharp distinctions are not always drawn between religions. The classical Chinese image of the three “vinegar tasters” shows Lao Tzu, Confucius, and the Buddha together, revealing different tastes of the vinegar. It attests to the syncretic co-existence of different religions. Buddhism not infrequently finds itself in this type of understanding and practice.

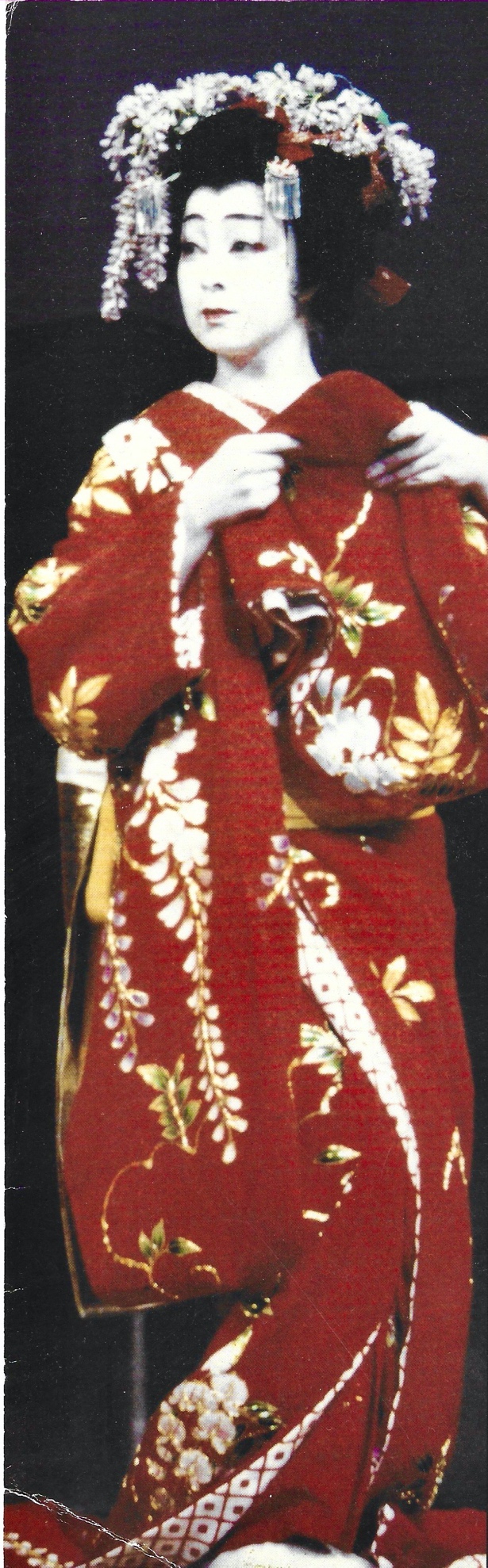

Fuji Musume, Wisteria Maiden performed by Fujima Kanso-o.

This image was on a banner flown from the National Mall in

Washington, DC, to promote the Smithsonian Institute’s

Edo Festival, in which Fujima Kanso-o performed.

Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Institute

Heidi Durning, sometimes performing as Fujima Kanso-o, has for the past 30 years carried out an evolving annual series, Moments in the Garden, held in the meditation garden of Eiun-in Temple, a small component of the large Kurodani Temple complex in northeast Kyoto. Shinji Dohi, the hereditary priest of Eiun-in, acts as a veritable curator in the use of the garden for performances. As he has aged and refined, so he has chosen to provide the garden for danced expression that too has refined over the years. Along with Durning, dancers Yurabe Masami and Rosa Yuki have been the core artistic team working with the priest.

Tamagoromo, a collaboration with Heidi Durning, Mori Mikayo, and Yurabe Masami. Eiun-in temple and garden, Kyoto, 2019. Photo by Uemura Ken

“Shinto is about life and nature. Every natural thing has a kami [spirit]. I have danced in Shinto shrines many times. Christianity is about praying for me. I remember even now German prayers that my father taught me as a child. Praying in a shrine is similar for me. Buddhism is about other worlds. My mother was killed in the Kobe earthquake in 1995. I created a dance in her honor, Ruby, that took me five years to make. It’s my most otherworldly piece, so perhaps it is Buddhist in that? With Noh theater and our love of folktales, there is certainly an aesthetic of the afterlife.”

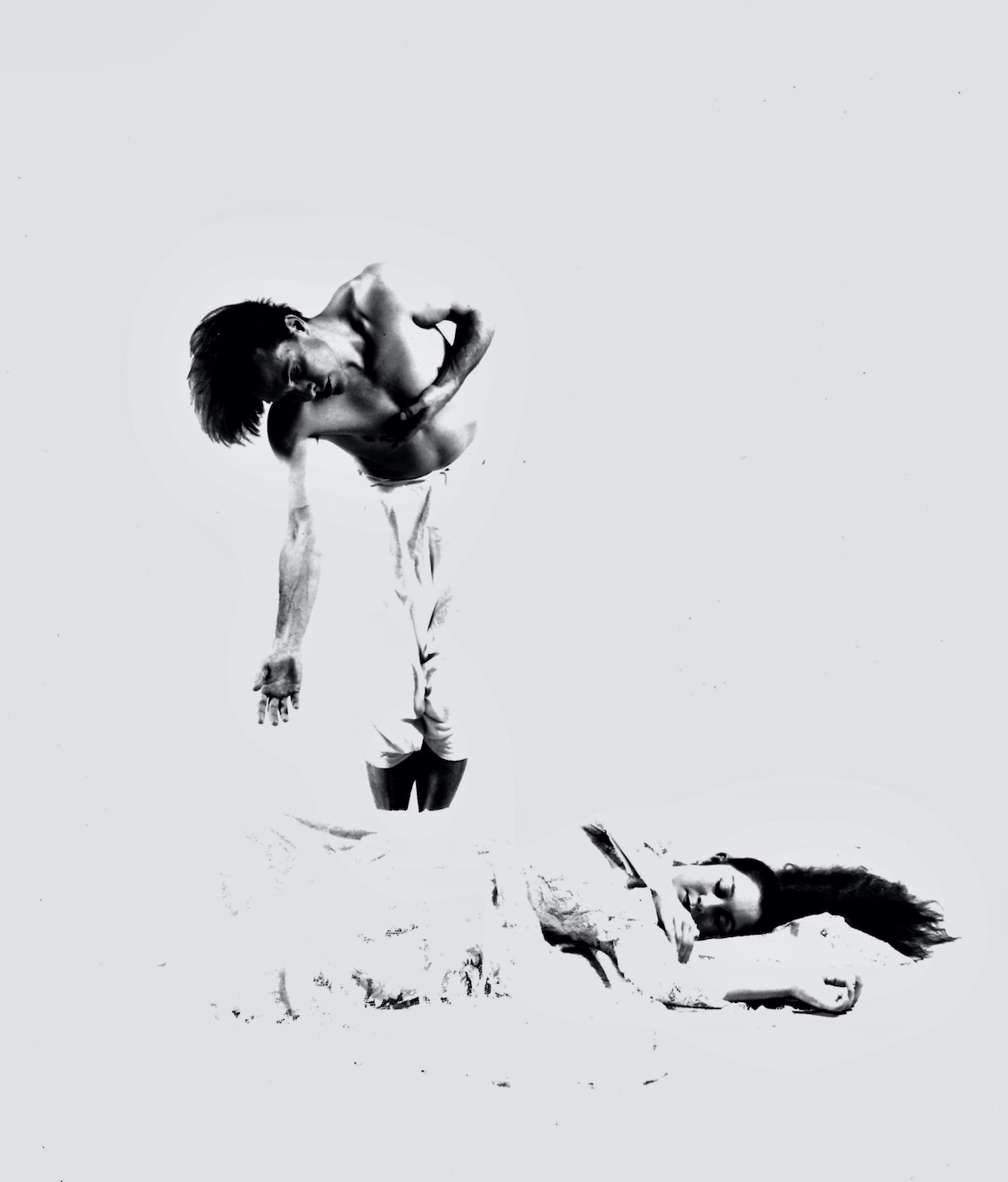

Iroha, All That Remains is the Fragrance of the Color. Heidi Durning and

Joseph Houseal. Kyoto, 1991. Iroha is a Heian period (794–1179) religious

poem legendarily associated with Kukai, the founder of esoteric Buddhism in

Japan. Iroha is a pangram of the Japanese syllabary alphabet using each letter

only once, and so small children learn about the transience of life as they learn

their ABCs. Photo by Uemoto Kenji. Image courtesy of Parnassus Dancetheatre

“In my own training, while there are years of modern and contemporary dance training, now at 63 I study with Eighth Grandmaster Kanjuro of the Fujima school of Nihon Buyo. There are several schools of Nihon Buyo. The Fujima school is the dance of kabuki, the buyo of ka-bu-ki. He is 40 years old, and I began with him at age 50. Remarkably, his father is a Noh actor of the Umewaka school! His mother was the Fujima Grandmaster, and he was wanted to lead both traditions. But he chose kabuki and took the title Eighth Grandmaster of the Fujima school. His grandfather, Kanjuro the Sixth, gave me my professional name, Kanso-o, years ago.”

Ruby, Heidi Durning, a dance of her mother in heaven. 2000. Durning’s mother was killed in the Kobe earthquake of 1995. This piece toured from Kyoto to Sweden, Korea, France, Greece, Brazil, and the US. Image courtesy of the artist

Ruby, Heidi Durning, a dance of her mother in heaven. 2000. Durning’s mother was killed in the Kobe earthquake of 1995. This piece toured from Kyoto to Sweden, Korea, France, Greece, Brazil, and the US. Image courtesy of the artist

The current Fujima Kanjuro is one of the most in-demand kabuki choreographers as newer forms of kabuki come to be. There is even one of a famous anime character Mikuhatsune, who—by means of motion-captured movement—performs Fujima-style dances in new kabuki thanks to Kanjuro. “This should not be such a surprise.” Durning explains. “Nihon Buyo was a pop dance to start with, on the riverbeds, a rage. It works well with pop culture, from the culture of Japanese printmaking centuries ago, to the productions of ‘Super Kabuki’ over these past decades.”

“I also study Noh with Mikata Shizuka, one of the top Noh actors of our time. He is also younger than me, about 10 years or so. Noh was never pop, always for the elite, the samurai, the shoguns, the priests. I am fortunate at this stage of life to have such top teachers. When people ask me how long I will continue performing, I always remind myself that the performing goes hand in hand with the training, and that must include practicing. So I will perform as long as I can train and practice.”

Ku. 2010. Heidi Durning performs in front of the Karukayado, part of the Mitsugo-in

compound at Mount Koya, as part of a two-day experience concluding with dance

and Noh flute. Arranged by David Aviolat, former counsul general of Switzerland.

Image courtesy of the Swiss Consulate, Japan

“I have performed at Mount Koya, the seat of esoteric Buddhism in Japan, and famous for the monk Kukai, or Kobo Daishi, who brought esoteric Buddhism from China in the early ninth century. My dance there was a commission to mark a journey to the sacred mountain, and so demarcating with forms evoking martial and ritual protection were appropriate as well for the type of mystical Buddhism practiced at Koya-san. Shingon Buddhism implies ritual rigor. After the effort of the pilgrimage, a vision of purity.”

Heidi Durning in collaboration with visual artist Tonomura Mayumi.

Kamigamo, Kyoto. 2001. Photo by Tonomura Mayumi

Fujima Kanso-o continued: “The Japanese concept of ma becomes more important to me as an artist; it becomes an agent of refinement. It relies in part on artistic intuition. Ma means space, or interval. Ma can be spatial, like the arrangement of rocks in a rock garden; or rhythmic, like the swelling space between two beats of a drum. Only with the second beat can ma be established and so the silence, the empty spaces, become enlivened, affecting mundane thinking into higher thinking; sensing an evolving rhythm, connecting the personal with the patterned.”

Sagi Musume, Heron Maiden. Kyoto, 1993. Heidi Durning dances

a fusion version of this Nihon Buyo classic, which she has also

danced. The spirit of a heron inhabits a young women to effect a

series of poetic transformations. Image courtesy of the artist

Shinji Dohi, the Jodo school priest-in-residence at Eiun-in, inherited the beautiful temple and garden from his maternal grandmother. It was built in 1591. The temple, garden, and some of the art within the temple are designated Important Cultural Properties in Kyoto. His own father is a pastor within the United Church of Christ in Japan. While Shinji Dohi was never baptized a Christian, he went to church every Sunday growing up, and spent long happy summers at Eiun-in with his grandparents. When destiny called him to accept his position at Eiun-in, he responded by developing his own personal understanding of being a religious person first, universally understanding the full range of what such a traditional and beautiful place could serve in the spiritual development of all people who come to a Buddhist temple and garden. They come for different reasons, all leave with a relaxed mind, a sense of time beyond the usual, and a living example of peace and one’s place in the world. He notes: “I never thought I would be a shaved-head!”

Ogyogi, Good Manners. Fujima Kanso-o and Joseph Houseal. Kyoto, 1989. Image courtesy of Parnassus Dancetheatre

After becoming a priest, shaving his head, and accepting his role of leader of Eiun-in, Shinji Dohi became involved in performing gagaku, the ancient music and dance rituals imported from China in the seventh century. That experience took him to the Montpellier Dance Festival in France, and there he connected with the Performing Arts Network, an organization he now directs. Shinji Dohi is committed to the revitalization of the arts, and providing a home for arts that share his interest in circulating energy across time and space, allowing the select audience to become part of the larger artistic and spiritual experience, and seeing Buddhism in a “new way.”

Purple Mountain. Socially-distanced performance at Eiun-in temple

and garden, Kyoto. 2020. Inspired by the traditional story Yamamba

of a mysterious, old but ageless woman appearing occasionally in

the mountains, savoring the changing seasons. Yamamba is

considered to be nature itself, and has versions in Noh theater,

Nihon Buyo, Bunraku puppetry and various folk tales.

Yamamba is an image of enlightenment in nature.

Photo by Keiko Yasumura Shogase

“I always laugh when people notice that I am doing ‘something new’ at Eiun-in,” explains Shinji Dohi. “I’m not. Buddhist temples in Japan have contributed to the development of all of Japan’s traditional performing arts. It is not unusual to see a gagaku stage at a Shinto shrine, or an outdoor Noh stage at a Buddhist temple. Traveling performers have performed at Buddhist temples for hundreds of years, showing kabuki before it was even kabuki, an earlier form, taking shape. When people see what a Buddhist temple can be—a place of repose for not only the dead, but for the living; a place of beauty that has transcended time, and lives on as a garden. A site where inspiring old art can be shared with a select group coming together to see special performances that reflect my idea of what religion in society should be, what art in a garden can be, and what Buddhism can offer the modern person in all their aspects.”

Omiwa from the dance theater play Imoseyama. Fujima Kanso-o

in the role that earned her professional status. Kaburenjo, Gion,

Kyoto. 1990. Image courtesy of the artist

Fujima Kanso-o brings her life to her art. Her stillness is as powerful as her movement; her silence as inviting as her fluid dance. Like a moon tracing its course across the sky, events take place in the garden at Eiun-in, never to be repeated and rarely to be forgotten. Eiun-in is a site normally closed to the public and used privately as a meditation garden for specially conceived and designed performances, restoring to modern Buddhism a modality of performance that once characterized historical Buddhism and the evolution of performance forms in the cauldron of Kyoto’s rich creativity. Less overtly religious than rites for the dead or the reading of texts, dances and art reflect the felt impressions of Buddhist awareness and are perhaps even closer to an experience of personal spirituality.

Yurari, Flowing. Heidi Durning. Shot in Fujima Kanso-o’s private

studio, Iwakura Kukan. 2001. Kimono painted by Sarah Breyer.

Yurari evokes the silent flow of early Spring air, the slow-motion

fade of daily drama, when in retreat with nature.

Image courtesy of the artist

See more

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Noh Now

Rarified, Recondite, and Abstruse: Zeami’s Nine Stages

Dance in the Reality You Have