FEATURES|COLUMNS|Ancient Dances

Zen Master Merce

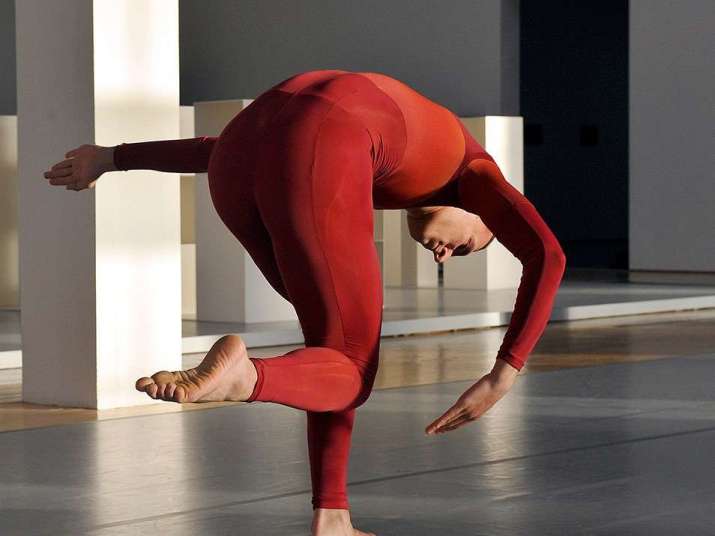

Merce Cunningham performs Changeling, a solo dance, in 1957. From Merce Cunningham

Dance Company. Studio shot by Richard Routledge

Zen is elusive and plain. Simple reality and a breaking through of all the other realities that we think are so real. By embodying Zen in his creative process and output, choreographer Merce Cunningham, who died at the age of 93 in 2009, transformed the terms of Western concert dance as he concluded the white aesthetic of philosophical formalism with a vast output of artistic collaborations, finding artistic and spiritual camaraderie with composers, artists, filmmakers, and designers. He was a humble, sweet, and luminous man.

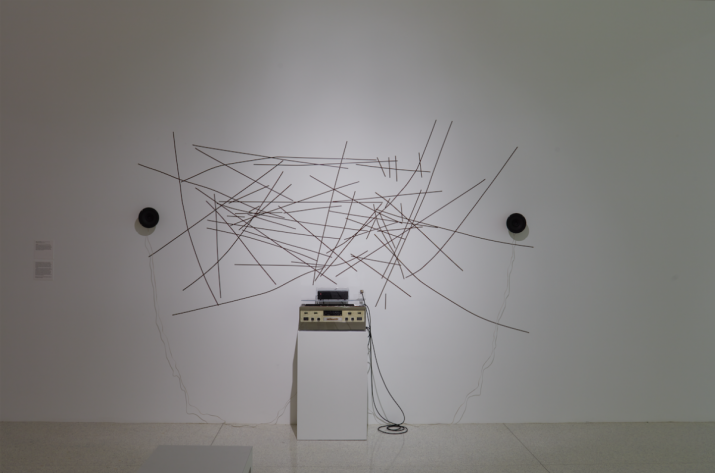

Nam June Paik, Random Access, 1963/2000. Audiotape, open reel audio deck, extended playback head, speakers installed, dimensions variable. Set piece for Merce Cunningham Dance Company. Photo from Merce Cunningham Common Time, 2017, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. p. 252-53.

Nam June Paik, Random Access, 1963/2000. Audiotape, open reel audio deck, extended playback head, speakers installed, dimensions variable. Set piece for Merce Cunningham Dance Company. Photo from Merce Cunningham Common Time, 2017, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. p. 252-53.Zen Buddhism extended deeply into the aesthetic and creative principles of Cunningham, whose partner in life and art was the avant-garde music pioneer John Cage, an anxious 20th century American composer whose life was transformed into one of joyful discovery through the Zen Buddhism taught to him by the great teacher Daisetsu T. Suzuki. Cage pierced through. Then he shared it with enthusiasm, with post-war Japanese artists such as Yoko Ono, with Fluxus artists in the West, and with a brilliant young choreographer named Merce Cunningham. Cunningham constructed the magnificent paradox, just as the classical Japanese dance theater Noh does: a highly theatrical, formalist artwork able to be experienced as a vehicle for the pure awareness of reality. In this he is like the greatest Zen poets and Noh masters.

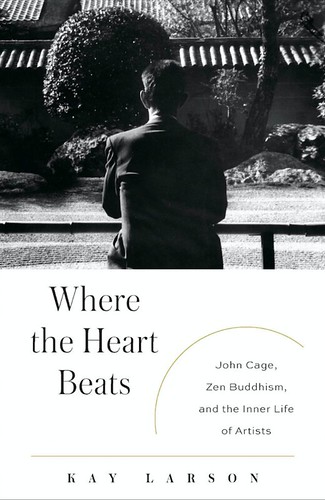

Kay Larson has written a remarkable book, a work of revelatory literature in itself: Where the Heart Beats. John Cage, Zen Buddhism, and the Inner Life of Artists. (Penguin Press 2012). Even the chapter headings indicate that she takes the subject head on—and that means with some wit: “Ego Noise,” “Zero,” and “Moving from Zero,” among them. Separate chapters are dedicated to John Cage, the Zen composer at the heart of it, and Cunningham the choreographer who gave his music visual life and collaborative possibility.

As Larson puts it: “Cage’s revolution was spiritual and musical, aesthetic and intellectual, theoretical and practical. Cage looked west to Asia, and learned a new Way of Being: let go of grasping; be the moment; celebrate eternal mutability; see the emptiness in a grain of sand.”

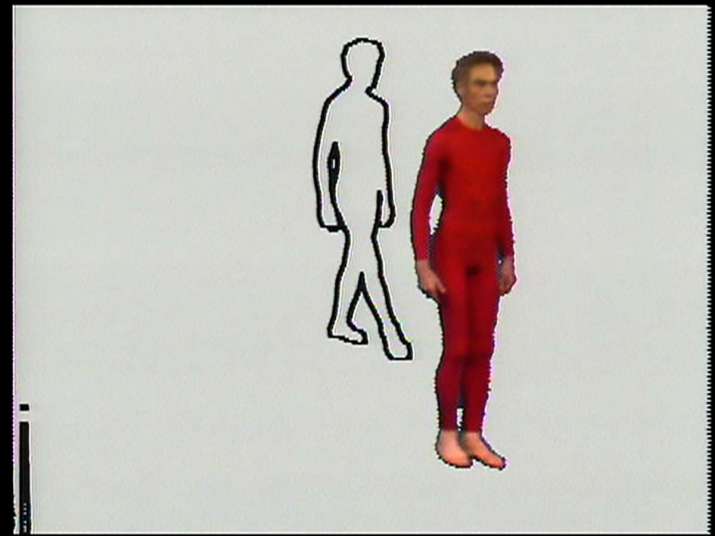

Charles Atlas, Nam June Paik and Shigeku Kubota, Merce by Merce by Paik, 1978. From Merce Cunningham Common Time, 2017, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. p. 254-255

Charles Atlas, Nam June Paik and Shigeku Kubota, Merce by Merce by Paik, 1978. From Merce Cunningham Common Time, 2017, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. p. 254-255Recently, Merce’s particular emptiness in a grain of sand was remarkably, splendidly ensconced for the future in a 48,000-square-foot, two-museum concurrent exhibition, Merce Cunningham, Common Time, created and presented at the Walker Art Museum in Minneapolis and the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) in Chicago. (8 February–30 June 2017).

Larson’s book succeeds in part because it knows well how to be a book. The Common Time exhibitions knew well how to be multi-art museum shows, challenging ways of presenting the combined arts, and daring to become a lasting expression of Merce’s aesthetic principles. This feat is all the more remarkable and necessary because Merce did something radical before he died: he instructed that after his death his company should be disbanded and his works cease being performed. The future is indebted to Larson, the MCA, and the Walker. Cunningham is not lost to history, in fact he leaves us with a big, beautiful, bold, but at the same time, light Zen koan, or reason-shattering riddle.

otheranimal by Ernesto Neto, installation, commissioned by Cunningham’s “Views on

Stage,” 2004. Image courtesy of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago

Simply experiencing reality is the paradoxical essence of his formalist aesthetic, and where Zen intersects with Western aesthetic philosophies. From the 1930s, 20th century America struggled with reality, philosophy, and populism, from the proletariat philosophies that became en vogue in the ‘30s, to the popular moral certitude of war in the ‘40s, to the fear of a philosophy in the McCarthyist ‘50s, to the popular radicalism of the ‘60s that used the alternative modes of drugs, sex, and Asian religion to reach reality, to the liberal hedonism of the ‘70s. Could popular culture handle reality, or did it always need a mollifying, too-populist mask? Where was art in all this?

Male dancer, Beacon Events, 2007-09. Installation by Sol LeWit, partial view, “1,2,3. All Three-Part Variations on Three Different Types of Cubes,” 1963–2004. From Dia:Beacon, 2008

Male dancer, Beacon Events, 2007-09. Installation by Sol LeWit, partial view, “1,2,3. All Three-Part Variations on Three Different Types of Cubes,” 1963–2004. From Dia:Beacon, 2008Remarkably, Cunningham succeeded in surpassing all of this political and social posturing to experience reality directly: this is the essence of Zen philosophy that influenced both him and Cage; and also Taoism, the principles of which he regularly employed and by which he lived his life. The simple principle of Common Time—that combined arts needed only share duration—guaranteed that reality would appear in a raw, unvarnished form. Neither the dancers nor the musicians knew what was going to happen any more than Cunningham or the audience. It was a genuine encounter with reality; a principle-based combination of artists, composers, and himself that reached a level of popularity unimagined for so abstract an endeavor. This is because the quality of the art was so high, the experiment so unrestrained, the aesthetic so pure, the result so giddy, and Cunningham so humble. Misunderstood? Often. Thought to be bad? Rarely.

Merce Cunningham Dance Company, Beacon Events, 2007–09. Installation by Sol LeWit, partial view, “1,2,3. All Three-Part Variations on Three Different Types of Cubes,” 1963–2004. From Dia:Beacon, 2008

Merce Cunningham Dance Company, Beacon Events, 2007–09. Installation by Sol LeWit, partial view, “1,2,3. All Three-Part Variations on Three Different Types of Cubes,” 1963–2004. From Dia:Beacon, 2008Indeed, the intellectual richness and nourishment of Cunningham’s output is one of the primary attractions for his many followers; why he was so widely appreciated by the French and Japanese, and why his legacy is suited to museum presentation. Cunningham and Cage can be called Zen artists as validly as any Japanese calligrapher or Noh actor. They created opportunities to pierce through all the layers of art to reveal: just this. It is breathtaking. And remarkable that two museums succeeded in showing this with the shared reality of their own common time. There is a little bit of genius in embodying the overarching metaphor with large buildings 410 miles apart.

Merce Cunningham: Common Time chronicles encyclopedically that it was in the art world, working with great artists, that Cunningham found his spiritual and philosophical peers; those who became his artistic collaborators. It was through understanding the more widely discussed art that people were helped in understanding Cunningham. There was little dance philosophy to help. The art and dance helped to explain the music, which was perhaps the most challenging element to understand and the least well presented in the exhibitions. It is Zen Buddhism that will continue to illuminate the work of all of these artists, and will continue to be a key for understanding a fundamental element in Merce Cunningham’s work: just this, experiencing and sharing reality.

Beachbirds for Camera, Merce Cunningham, Elliot Caplan 1993, 30:01 min, color and b&w.

From Cunningham Trust

Have I ever seen so vast an exhibition as those 48,000 square feet of Cunningham’s dance works and those of his collaborators? Then why do I walk away refreshed, delighted, stimulated, full of new thoughts? There is nothing overbearing; nothing accumulates into anything other than the simple reality Cunningham showed again and again. This is fully captured in some of the many excellent films, such as those by Charles Atlas and Eliot Kaplan, in the astonishing documents provided by the Jerome Robbins Dance Division of the New York Public Library, in the historically iconic photographs, and in the performance remnants of art—set pieces, old electric fans, Victorian lace dresses, allusive contraptions prefiguring Tantric Buddhism—owned variously by museums and private collections.

Robert Rauschenberg, set pieces and costumes for Travelogue, 1977. Photo from the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. This artwork was influenced by Tantric Buddhism

Robert Rauschenberg, set pieces and costumes for Travelogue, 1977. Photo from the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. This artwork was influenced by Tantric BuddhismOf course Cunningham’s company performed events in museums long before anyone else did, and so awakened fine art appreciation for his movement experiments, while refocusing object-biased museum culture toward appreciating the immediate moment—something that propels the entire exhibition. But his influence on art was not so much from these happenings as from his influence on artists, and the popular forum he provided them with theatrical dance. Beyond this, the museums show us that the Cunningham legacy is in safe hands: theirs.

There is no “just this” in dance companies falling over themselves to keep the founder’s dances going on because they were so great. Cunningham knew his company team would do this and that is precisely why he instructed that the company be disbanded and his work stop being performed save in special situations. After the leaves have fallen, it is nothing short of desperate to throw them back in the air to pretend it is time for apple cider. The detachment provided by Cunningham’s serious art allows one to contemplate an experience of reality, offering new understandings and artistic pleasure. That his dances will no longer be performed is not at all the point, as this traditional Zen poem reflects:

A perfect cloud

Revealing a perfect moon.

If it lasted longer,

More perfect?

David Vaughn, Merce Cunningham, and John Cage rehearsing How to Pass, Kick, Fall and Run. 1970. Image courtesy of Brooklyn Academy of Music

David Vaughn, Merce Cunningham, and John Cage rehearsing How to Pass, Kick, Fall and Run. 1970. Image courtesy of Brooklyn Academy of MusicIt is easy to overlook the importance of Buddhism in stimulating and inspiring artists. It has done this for centuries, as the media change, along with religion and culture. For principle-based artists, Buddhism supplies a richness that has brought the world such stunning works as the superabundant Dunhuang Cave paintings, and John Cage’s infamous piano piece 4:33, during which a pianist sits in silence on a piano bench for 4:33.

References

Larson, Kay. 2012. Where the Heart Beats. John Cage, Zen Buddhism, and the Inner Life of Artists. London: Penguin Press.

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Tibetan Book of the Dead, Part One: Cosmic Jumper

Tibetan Book of the Dead, Part Two: The Hour of Our Death

Tibetan Book of the Dead, Part Three: One Last Dance

Meet the Khandum