FEATURES|THEMES|Meditation

A Better Question

From Sit With It: A New Paradigm for Living by Xavier Alexander Vazquez. Image courtesy of the author

From Sit With It: A New Paradigm for Living by Xavier Alexander Vazquez. Image courtesy of the authorThe Buddha’s First Noble Truth is hard to argue with no matter what your religious beliefs are. It states that life is full of suffering. It is certainly hard to escape the poverty, violence, war, starvation, health crises, and ecological disasters occurring in the world today. Everyone—the poor, the rich, the left, the right, the sick, and the healthy—faces some level of day-to-day stress and strain. Living is commonly understood to be a struggle, a battle that must be fought in a slow onward march toward old age and death.

Yet things are not necessarily as they seem. Everything that we know has passed through the intellect of others before reaching our own, almost like a baton handed from person to person. The cultural contents of our society, including its most basic assumptions, have been crafted over thousands of years of conceptual baton-passing. One’s perspective on life is inherited from key influencers during childhood. It is then reinforced as we grow into adulthood through observation of, and experience within, the very society that introduced our perspective in the first place. Some basic thoughts and assumptions about the world have become so widespread that we mistakenly understand them to be indisputable truth. We operate within inherited paradigms of perception and, most often, don’t even realize it.

Our current paradigm, relegating life to a battlefield, results in The Big Questions:

“What’s the purpose of life?”

“How does one attain happiness and peace while avoiding suffering?”

From Sit With It: A New Paradigm for Living by Xavier Alexander Vazquez. Image courtesy of the author

From Sit With It: A New Paradigm for Living by Xavier Alexander Vazquez. Image courtesy of the authorHuman society has generated countless answers to these questions since prehistory. Solutions to the problem of suffering come from a wide array of sources, such as family tradition, religion, academia, business, politics, science, psychology, the arts, and phenomena like the self-help and New Age movements. But we seem to be no closer to conclusive answers than our ancestors were. Asking these questions has been a long-running exercise in futility because much of what we have been taught about existence is based on an inherited faulty assumption: that the answers to The Big Questions can be found somewhere out in the world.

If we are to properly address the dilemma of suffering, happiness, and purpose in life, we must first understand that the multitude of solutions provided by society will not bring us the resolution we crave. Instead of seeking to attain happiness and peace, or arguing about the purpose of life, one can ask a simple question that may, in fact, undermine the credibility of our current inherited perception paradigm:

“What do I feel when sitting quietly without distractions?”

From Sit With It: A New Paradigm for Living by Xavier Alexander Vazquez. Image courtesy of the author

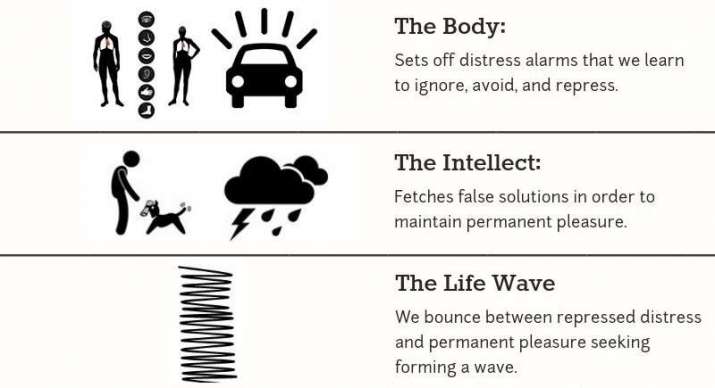

From Sit With It: A New Paradigm for Living by Xavier Alexander Vazquez. Image courtesy of the authorUnfortunately, we often ignore or even intensly avoid discomfort in our daily lives. We have internalized two incredibly counterproductive inherited notions. The first, suffering is unacceptable. The second, suffering can be solved the way one would solve a math problem: by finding the right solution. These two beliefs propel us into an addictive mode of being in which we continuously strive for pleasure and comfort. The Buddha described this state of being in the Second Noble Truth.

Sitting quietly without any external stimuli is so uncommon that many of us do not have an answer to this question. For those who do, some think non-activity is boring and even consider it laziness. For others, the concept of stillness conjures ideas of peace, tranquility, and equanimity. This idealized notion has made the practice of meditation popular. But in actual practice, one may find that discomfort, unease, anxiety, racing thoughts, and even body pain arise when activity ceases. These uncomfortable sensations do not mean that sitting should be avoided. Instead, sensations that arise during sitting can be understood to be a form of communication from the body, which is intelligent in its own right and, in many respects, operates independently from one’s conscious volition. The discomfort felt during non-activity is the body’s request for attention.

From Sit With It: A New Paradigm for Living by Xavier Alexander Vazquez. Image courtesy of the author

From Sit With It: A New Paradigm for Living by Xavier Alexander Vazquez. Image courtesy of the authorEach of us has a reservoir of discomfort underlying the activity of our everyday lives. These signals from the body are drowned out by constant pleasure-seeking activity. We devour everything the world provides us in search of the right solution to distress—from holy spirituality to crass materialism. This traps us in a cycle of gain, loss, pleasure, and pain. Humanity is chaotic at the macro level because almost every civilized human being is essentially an addict: regularly using the people, objects, and situations in our lives to avoid internal distress and maintain consistent comfort and pleasure.

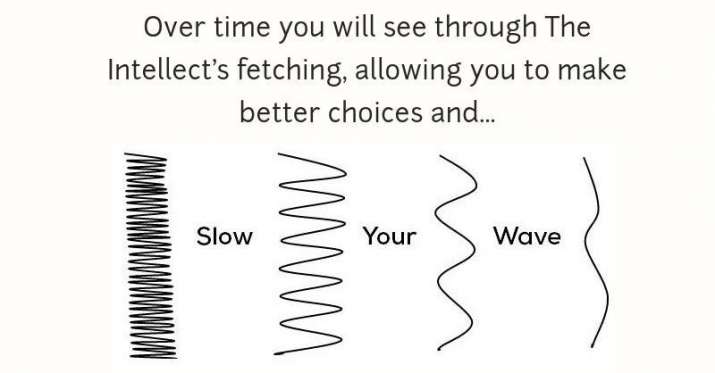

We need a new paradigm for living. It is time to set aside inherited notions about what life is, what suffering is, and retire The Big Questions. It may be possible to move past the conditions described in the First and Second Noble Truths. Do not take my word for it. Find out your answer to the question: “what I do feel when sitting quietly without distractions?” Schedule a few minutes of quiet sitting every day. Once you open a channel of communication with the body, you may be able to create a different relationship with discomfort. One which does not involve avoidance of distress and constant solution seeking. A new relationship with the body may alter how you interact with the people, objects, and situations in your life, which in turn creates the world anew.

See more

Sit With It: A New Paradigm for Living

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

The Daily Practice of a Modern Chinese Buddhist Nun: Facing the Discomfort

Gladden the Mind: Four Ways to Practice with Negative Thinking

The Positive Impact of Mindfulness

Bringing Awareness Practice from Retreat into the World