FEATURES|COLUMNS|Dharma Project of the Month (inactive)

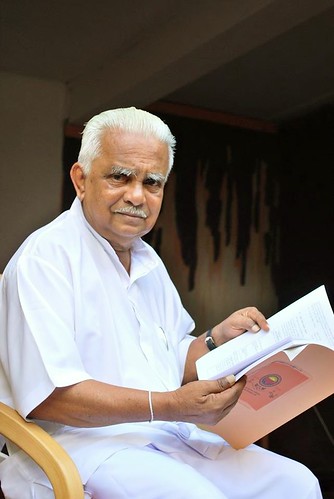

A Moment with Dr. A. T. Ariyaratne

Archive photo of an early Shramadana camp

Archive photo of an early Shramadana campIt was just four days after one of the worst floods to hit Sri Lanka in the last 20 years that I arrived at the headquarters of Sarvodaya, the country’s most broadly embedded community-based development organization, in the Colombo suburb of Moratuwa. As expected, the compound was abuzz with activity: sacks of rice, bottled water, and other necessities filled the narrow reception, while in the courtyard, about 50 volunteers, mostly young people, were sorting through relief supplies under the direction of Neetha Ariyaratne. Amid this flurry of action stood Dr. A. T. Ariyaratne—Dr. Ari or Loku Sir as he is called by his staff—composed as ever, quietly taking in everything that was happening.

I apologized for my ill-timed visit, aware that everyone here must be totally occupied with flood-relief efforts, but in his usual affectionate manner, Dr. Ari took my hand and motioned me to his small office. “It is OK, my dear,” he replied. “Our disaster management center has activated its operations and is coordinating with the respective Sarvodaya district centers and divisional secretaries in their efforts.”

We were briefly interrupted by one of his staff who wanted his signature for some documents.

“We have had floods and disasters all throughout our history. Whenever a disaster has occurred, Sarvodaya has been at the forefront. Just over the past few days, we have helped more than 5,000 people in five districts. We draw on our reserves while waiting for pledges from overseas. We are doing what needs to be done in our own quiet way. Not a word in the media. It has nothing to do with the government, the various companies like the TV station, and so forth. But today, Sri Lanka is totally spoilt, particularly after the 2004 tsunami. Everything is commercialized. Even relief efforts have become a commercial thing. Everywhere they take the accreditation and advertise that this or that was given by so-and-so. This is opposed to the Buddhist spirit of giving. It’s a sin. If you give, you should give without expecting anything in return. You give to reduce the greed you have in your mind, to get rid of hatred, to get rid of ignorance, which will get us out of samsara. Because if you give anything and advertise, you don’t get any kusala or merit.”

Dr. Ari has every right to be forthright in his words. His courage is born of the moral power that those who live by the Dhamma are protected by the Dhamma.

Distribution of flood relief

Distribution of flood reliefOne of the most respected Sri Lankans locally and globally, this diminutive 86-year-old dynamo has seen more than his fair share of upheavals in his life. He has been harassed by enemies, challenged the political leaders of the day, confronted the Tamil Tigers, and has stared an assassin in the face. The educational experiment he started with a group of students in a poor, backward village called Kanatoluwa in 1958 has evolved into the biggest and most progressive development movement in the country, with an extensive network that covers 15,000 villages and has impacted the lives of millions of people.

During the first 20 years of the Sarvodaya Shramadana Movement, Dr. Ari himself personally led more than 35,000 young people aged 16–24 years old to hundreds of villages. Each group stayed in a village for a minimum of seven days and spent 6–8 hours daily on physical labour. In the evening, they would sit with the local villagers for three hours, sharing and talking about their problems. Village after village, he engaged people with the motto: “We build the road and the road builds us.”

Dr. Ari leading a mass meditation practice

Dr. Ari leading a mass meditation practiceThe Sarvodaya Shramadana camps focused on meeting basic, simple needs with an emphasis on active community participation. The word “shramadana” translates into the giving of one’s time, energy, and money on a non-profit, voluntary basis toward uplifting less privileged communities and is an extremely noble endeavor. In a Shramadana camp, hundreds of villagers work side-by-side to construct something they democratically decide is important to their common welfare. For example, when there is no clean water, villagers and volunteers will start building wells, starting perhaps with one well for every three families.

Children and grandparents, men and women of all religions and castes, rich and poor alike, lift shovels and carry dirt, sing together, learn about community organizing, and sometimes move mountains. Everybody has something to offer—effort, time, skills. Physicians can give of their expertise in treating various illnesses and helping with health issues. Engineers can lend their skills to design wells or school buildings. And for the first time, a university professor has the opportunity to find out how little he knows about the life of a farmer, and vice versa. A truly humbling experience for all involved.

Dr. Ari with his wife Neetha

Dr. Ari with his wife NeethaReflecting on the current situation in the country, Dr. Ari laments, “In the old days, we had a very happy and simple way of living. We had clean water, clean food, a clean house, simple clothing. Nothing luxurious, but we were very happy. Then started the rat race, when we all wanted money, power, and luxury. Then the violence started. In those days, it was very rare to hear of a murder. These days, you find killings and violence daily in the headlines. On top of that, there is a new thing called terrorism. Before we talk about economic development, we should put our Buddhist values back in place.”

In his view, development that emphasizes the acquisition of more and more material things promotes greed, hatred, and ignorance. “Such development is simply not sustainable and not in sync with our Buddhist values. What we have adopted is an economic and political system that is ill suited for Sri Lanka, a curse of the West.” Dr. Ari observed. “The recent Meethotamulla garbage disaster and the present mudslides from the rains—all these happen because of the environmental damage wrought by unbridled mega development projects, corrupt practices, and poor governance. Today, we have superstructures where power and wealth is concentrated in the hands of a few. These superstructures are crushing us. To change things, we, the ordinary people, must take over the management of our own lives from the superstructures we have built.”

Meeting with Tamils in northern Sri Lanka

Meeting with Tamils in northern Sri LankaFor real transformation to take place, there must be an alternative economic and political model, one that seeks to empower the ordinary man with jana shakti or people’s power. The ultimate aim is to build up sustainable village communities that are self-reliant, and individuals who are responsible for their own well-being and those of others.

Sarvodaya’s bottom-up model of grama swarajya, or village self-governance, is being implemented in 3,000 villages across the country. In each village, Sarvodaya works through a five-stage intervention model that includes needs assessment, community mobilization, setting up self-help institutions called Sarvodaya Shramadana Societies, impact measurement, and extension of support for other village communities. Each village receives a customized mix of products, services, and activities in economic development, peace building, and emergency relief.

Rice and other necessities arrive for flood relief

Rice and other necessities arrive for flood reliefHowever, to see the Sarvodaya Shramadana Movement as a rural development program or social movement is short-changing its higher objectives.

“Sarva” means All and “Udaya” Awakening. At the core of the Sarvodaya Shramadana Movement is the affirmation that all human endeavors should be directed at awakening on many levels—personal, family, community/group, society, and world. Hence, all of Sarvodaya’s initiatives are mindful of the goals and processes of inner cultivation by which man can transcend his attachment to craving for material possessions, to eschew violence and hatred, and to overcome ignorance.

Sarvodaya staff carries out needs assessment in a village

Sarvodaya staff carries out needs assessment in a villageThe path to total awakening can be realized in the true spirit of service to others, as Dr. Ari explains: “Every human being, particularly the Buddhist, must think of the well-being of all as our objective. If we are to realize Bodhi or the highest levels of intelligence that any human mind has the capacity to attain, we have to serve all living beings and help them overcome physical, mental, and emotional suffering. This truly is the Bodhisattva ideal. This is our supreme goal and it may be called total personal awakening.”

Dr. Ari explained how, through participation in Shramadana activities, we learn to consider the whole of humanity and the living world as one. We develop loving-kindness (karuna) toward all beings. We respect all life and preserve all sentient beings, as taught in the Karaniya Metta Sutta. This quality of loving-kindness translates into compassionate action (metta) as we strive to alleviate the suffering of all beings, such as in digging wells, helping the sick, or building a road or school. By engaging in such meritorious deeds, one enjoys maximum mental well-being and develops altruistic joy (mudita). One can then progressively develop a state of mind not disturbed by loss or gain, name or shame, success of failure; the quality of equanimity (upekka). Thus, in trying to help awaken all, one awakens oneself simultaneously.

Sarvodaya’s disaster management team works in the most difficult areas

Sarvodaya’s disaster management team works in the most difficult areasMore than 60 years on, Sarvodaya continues to embody the meaning of its name—the sharing of labour, thought, and energy for the awakening of all—spiritual, moral, cultural, social, and political. In this unique exercise, not all may reach Nibbana, but for most of us, the world could become a more satisfactorily fulfilling and beautiful place to live.

In Dr. Ari’s words: “The greatest message that Sarvodaya gives to the world in the 21st century is the message of peace and tolerance. Such a message can only be realized when it begins in the human heart. It should thus begin in the individual and then flow to family, community, society, and the world. Tolerance of others, equality and sharing of resources and power without the exploitation of human beings is the final objective. Violence should be eschewed at all levels. It is in such a context where we learn to tolerate our differences and refrain from exploiting others that a new world order may be created.”

Photos courtesy of Sarvodaya.

See more

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Venerable Tsunma Lobsang Rinchen Khandro: Acting with Compassion for All Those Suffering from Adversity

Lessons of the Principle of Dependent Arising for Politics and Investing

Embracing the Mekong in Distress

Marginalized and Ignored: The Corrosion of Bangladeshi Minority-Government Relations