FEATURES|COLUMNS|Mindful Capital

Are Minimalism and Fo-xi Threatening the Consumer Economy?

From nosidebarcom

From nosidebarcomMinimalism as a lifestyle has been a topic of much interest over the last few years. One of the thought leaders in this area is Marie Kondo, a Japanese “decluttering” and “organizing” consultant who advocates managing our belongings and possessions by methodically gathering them together, one category at a time, then holding on only to those that “spark joy” in our lives. Each of our possessions should serve a function and we don’t need to own multiple sets of them, says Kondo: the items we decide to keep should each occupy a designated place in our home so that we can easily find and make good use of them.

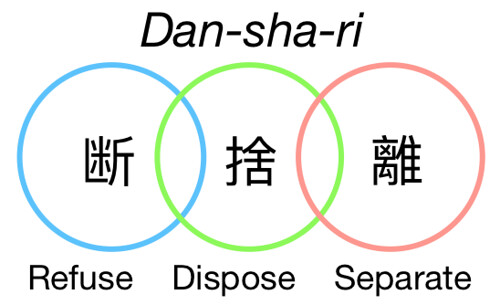

Another prominent voice in the minimalism movement is Hideko Yamashita, who teaches the practice of dan-sha-ri (断捨離), which means to “refuse” unnecessary new purchases, “dispose” of existing clutter, and “separate” oneself from the desire for material possessions.

In our consumption-based economy, our purchasing decisions are often more driven by our desires than our needs. While we all have basic requirements to keep our body and mind nourished with food, clothing, and shelter, our desires for design, beauty, and quality are manifestations of self-gratification. Yet these objects of desire often appear on everyone’s list of “must-haves.” Some of us may have so many extra appliances, utensils, gadgets, items of clothing, and so on, that they are rarely used, even while the basic needs of the underprivileged members or our communities are not being met.

It is indeed a paradox in our consumer economy that we appear to prefer more choices, but too much choice stresses us out (Schwartz 2004)—it is not only difficult to decide what to buy, it is also difficult to decide what to consume after we have made our impulsive purchases. Making choices could be much easier if we kept things simple. Steve Jobs, Albert Einstein, and Mark Zuckerberg are all known for simplifying their wardrobes by wearing similar clothing each day, in a deliberate effort to leave more time and energy for the more important decisions in life.

But a minimalist lifestyle need not be boring. It is about dedicating the best object for the circumstances, one item at a time. Perhaps the Japanese approach to minimalism has very “Zen” characteristics because Zen involves a process of unifying the mind and the development of insight facilitated by acute focus. Simplicity can still be articulate, tasteful, and enjoyable. In the spirit of Zen and such modern mindfulness practices as drinking tea, flower arranging, and eating, we can find deeper meaning and experiences even in very simple and basic activities.

On the other hand, recent trending media discussions in Asia of the fo-xi (佛系; literally the “category of Buddhist”) mentality is not only quite different from the aforementioned minimalistic lifestyle, but also very different from Buddhist philosophy. In essence, fo-xi might be described as a laidback or wishy-washy attitude, in contrast with a hungry, aggressive, and “wolf-like” mindset. Fo-xi advocates find it too stressful to care, and prefer to keep things simple; because it is messy to choose one way or the other, it is better to “let it be.” This approach might appear to resonate with minimalism, but true minimalism involves a conscious choice to keep life small but beautiful—imagine how hard it is to choose only one bowl to use and resist the desire to acquire another. It can be quite hard work, in fact. Not to mention decisions over our clothing, shoes, and so forth. The fo-xi attitude is also quite different from Buddhist philosophy because Buddhism teaches impermanence (Skt: anicca), unsatisfactoriness or suffering (Skt: dukkha), and non-self (Skt: anatta), and addressing our core and innate defilements of greed, hatred, and ignorance requires in-depth learning and practice in daily life.

To briefly illustrate these key concepts, greed is the desire for more of what we like, hatred the desire for less of what we dislike, and ignorance the inability to see beyond the delusions of our own views, including our likes and dislikes. While the lack of desire exhibited by fo-xi seems simple and non-attached, at a more subtle level it is not led by the wisdom of transcending beyond views, but manifests a dislike against taking any view. There is a strong element of indifference and a lack of motivation in the spirit of fo-xi.

In the Sabbasava Sutta the Buddha says, “Monks, the ending of the fermentations is for one who knows and sees, I tell you, not for one who does not know and does not see.” (MN 2)

The Buddha taught that the cessation of stress and suffering requires one to know and to see. It requires us to know and see the truth about the real nature of our “self” and our experienced world, which is, according to the Buddhist teachings, impermanence, unsatisfactoriness or suffering, and non-self. “Fo-xi” holds the view that there is an everlasting and eternal self who is laid back and wishy-washy, which suggests, as the Buddha said, that they are not really free from suffering and stress. This wrong view of self will keep them bound, “not freed from birth, aging, and death, from sorrow, lamentation, pain, distress, and despair.” (MN 2) The true fo-xi should also not be equated with void-ness or nihilism, which negates the value of moral efforts and hence any potential for personal development.

Hence, it is important for fo-xi advocates to know and see the true nature of the self and our experienced world; the fact that there are different levels of happiness and that it is worthwhile to sacrifice lower levels of happiness for higher levels: i.e. reaching a higher level of freedom from stress and pressure takes effort. We are responsible for our happiness as much as we are responsible for our moral actions.

From treadingmyownpath.com

From treadingmyownpath.comDo minimalism and the fo-xi lifestyle pose a threat to the consumer economy? It should not be a real concern because while there is a strong notion of self, there are strong notions of likes and dislikes, which remain subject to the maneuverings of the consumer economy. Indeed, it did not take long for consumer corporations to respond to the minimalist and fo-xi lifestyles—new products and advertising and branding campaigns targeting minimalists and fo-xi consumers very swiftly appeared. Being minimalist or fo-xi is also an identity and, like all identities, maintaining it requires a certain level consumption!

References

Sabbasava Sutta: All the Fermentations (MN 2). Translated by Thanissaro Bhikkhu. Access to Insight (BCBS Edition).

Schwartz, Barry. 2004. The Paradox of Choice: Why More is Less. New York: Ecco, HarperCollins Publishers.

See more

Taking minimalism to the next level (The Japan Times)

'Buddha-like' frog game leaps into hearts of young Chinese (The Straits Times)

Steve Jobs Always Dressed Exactly the Same. Here's Who Else Does (Forbes)

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Tam Po Shek Interview: Spiritual Living through Photography, Music, and Art

Maia Duerr: Zen, Life, and Livelihood

Happiness, Expectations, and Learning to be Losers: An Interview with Ajahn Brahm

Buddhistdoor View: Cultivating Non-Attachment in the Midst of Pressured Living

Related news from Buddhistdoor Global