FEATURES|THEMES|Commentary

Buddhistdoor View: Preta, Materialism, and the Insatiable Appetite for “Things”

Apple CEO Tim Cook unveils the IPhone 7 on 7 September 2016. From fortune.com

Apple CEO Tim Cook unveils the IPhone 7 on 7 September 2016. From fortune.comMore than enough has already been written about Apple’s innovative marketing of the iPhone, from its successful debut in the global market as an “affordable” luxury product to the way it has captured the imagination of a large segment of the population as “the” smartphone to have. Competing models from rival companies—even those handsets that outperform the iPhone in some respects—have struggled to achieve quite the same level of brand recognition. Every launch of a new model, such as this year’s iPhone 7 and 7 Plus, generates a contagious buzz of speculation, praise, and criticism in the press and throughout social media.

Each year, global marketing campaigns for the latest must-have consumer products become increasingly sophisticated. The branding power of the iPhone, for example, has seeped into the fabric of developed and developing economies alike, where aspirational middle class populations offer the prospect of immense spending power to the world’s manufacturers. The iPhone continues to be phenomenally popular in China as well as in India, Indonesia, and other economically significant markets.

Apple and other influential brand-setters know how to appeal to two fundamental aspects of our materialistic desire. The first is the desire for a high-quality product with benchmarks that appear to match or surpass established industry standards (such as a larger screen, or a higher-resolution camera). But beyond technical specifications, iPhone fans are drawn to the perception that their devices represent a lifestyle, an aspiration, and a sense of belonging to a self-referential club or segment of society.

The second motivation is less tangible than the first, but arguably much more potent and valuable to consumer product makers such as Apple. It appeals into the public’s endless hunger to upgrade to something perceived as “better,” often before the preceding model can even be considered “old.” The previous iPhone iterations, for example, the 6S and 6S Plus, were released only last year, and the case for upgrading is often dependent on “bells and whistles,” gimmicks that create a sense of lack and anxiety in the consumer that can only be filled by acquiring the latest version. A kind of “multifaceted materialism” fuels the drive for “more” and “better.”

Observing the global flurry of pre-orders and those notoriously long overnight queues outside Apple Stores that demonstrate the seemingly irresistible draw of products like the iPhone, it is hard not to be reminded of the endless hunger of the preta of Buddhist lore. Translated as “hungry ghost” (Pinyin: e gui) in Chinese mythology, pretas dwell in one of the six realms of rebirth in traditional Buddhist cosmology. They appear as gangly, stick-thin creatures with large bellies that indicate their extreme hunger and thirst. However, they have necks as reedy as straws—so thin that they are forever unable to consume nearly enough of the food they crave. A preta is not a being to be feared but rather to be pitied; it is physically impossible for these creatures to satisfy their hunger until they die and are reborn as more karmically fortunate beings.

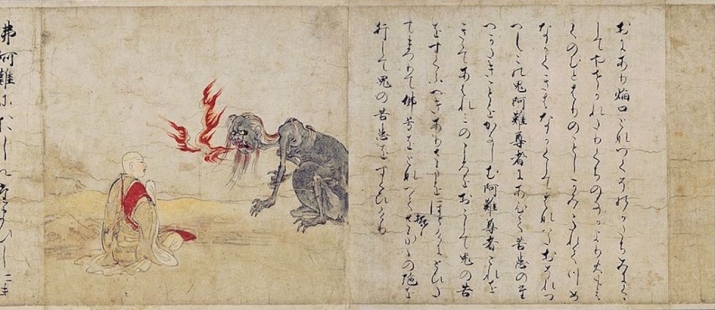

A segment of the 12th century Hungry Ghosts Scroll at Kyoto National Museum. From commons.wikimedia.org

A segment of the 12th century Hungry Ghosts Scroll at Kyoto National Museum. From commons.wikimedia.orgThis is not to say that iPhone fans are pretas, of course!* However, the never-ending hunger of pretas can be seen as an allegory for a more general problem surrounding societies and economies built upon consumption. The problem is actually due to two overlapping factors. Companies, particularly those that enjoy brand power and recognition, are voraciously seeking to outdo each other for the attention of consumers. Consumers, meanwhile, compete with one another to own the most prestigious brands to temporarily boost the non-existent self’s sense of identity and worth.

The iPhone is unquestionably one of these brands that is currently highly sought-after. The perceived desirability of the iPhone is predicated on the self-referential status of owning the latest, greatest model. Therefore, we allow ourselves to be wooed by marketing campaigns into chasing after “shiny things” that can never truly satisfy us for long, as advertisements for the next upgrade cycle will subtly remind us.

Perhaps it is time for us, as individuals, to pause and question this “need” to upgrade to the newest and best model—is an iPhone 7 Plus truly necessary? (It’s very likely that one’s existing handset still functions perfectly well.) It could also be helpful to encourage intellectual countercurrents against the ever-present frenzy of consumerism around smartphones and other objects of desire.

This is not necessarily to say that Apple does not deserve its success. Innovation is a powerful engine of economic growth and prosperity; it can make our dreams come true. But when combined with the desire for the ephemeral gratification of keeping up with the latest and greatest, the result is an unrestrained, cross-cultural materialism that resembles the tragically insatiable hunger of the preta.

* A declaration of interests: most of the Buddhistdoor editorial team use Apple computers!