FEATURES|COLUMNS|Theravada Teachings

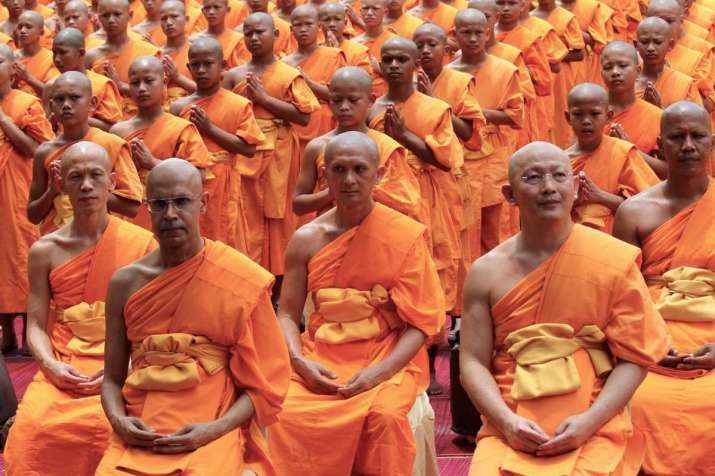

Chanting in Concord

The Sangiti Sutta, Digha Nikaya 33, contains teachings, perfectly expounded, in groups of five, to be mindfully chanted by the sangha, in concord, for the happiness of devas and men, which may be condensed and compacted as follows:

There are five grasping aggregates: material form, feeling, perception, volitional formations, and consciousness.

Five kinds of sensual stimulation: sights seen by the eye, sounds heard by the ear, smells smelled by the nose, tastes tasted by the tongue, touches felt by the body which are pleasant, likable, desirable, and agreeable, arousing passion.

There are five realms following rebirth: purgatory, animal realm, ghost realm, human realm, and the realm of the devas.

Five ways of being ungenerous, regarding: abode, family, possessions, praise, and not sharing the Dhamma.

Five hindrances of: sensuality, ill-will, dullness/drowsiness, worry/restlessness, and skeptical doubt.

Five lower fetters: abiding self, doubt, wrong discernment regarding rules and rituals, sensuality, and malevolence.

Five higher fetters: craving for the world of form, for the formless world, conceit, restlessness, and ignorance.

Five moral precepts, refraining from: taking life, taking what is not given, sexual misconduct, speaking falsely, intemperance involving drugs and alcohol, leading to negligence.

There are five things an arahant, with defilements ended, is incapable of intentionally doing: an arahant cannot deliberately take the life of a living being; cannot take what is not given; cannot indulge in sexual intercourse; cannot tell a deliberate lie; cannot store up goods for nourishment.

Five kinds of loss: a sentient being is reborn in a place of loss, in a bad place, in the underworld, in hell, it is not due to the loss of relatives, or wealth, or health, but rather due to loss of character and/or right view, causing the body to break up after death.

Five kinds of gain: it is not dependent on gain involving family, wealth, or health that sentient beings are reborn in a good place or in a heavenly realm, but rather dependent on being endowed with virtue that sentient beings are reborn in a good place, in a heavenly realm.

Five blessings accrue to the righteous devotee dependent upon his practice of virtue: gaining substantial wealth based upon diligence; getting a good reputation; having confidence when entering an assembly of aristocrats, brahmins, householders, or ascetics; meeting death serenely; being reborn in a good place, a heavenly realm.

A monk who wants to chastise another should bear five things in mind: speak at the proper time, not at an improper time; speak truthfully, not falsely; speak gently, not harshly; speak beneficially, not harmfully; speak lovingly, not harmfully.

Five factors supporting meditation: here a monk has faith, trusting in the enlightenment of the Tathagata; trusting that the Blessed One was perfected; a fully awakened Buddha; accomplished in knowledge and conduct; a well-farer, knower of the world, a supreme guide for devotees; a teacher of gods and humans; awakened; blessed; rarely ill or unwell; digesting food well; neither too hot nor too cold; but just right for meditation.

A virtuous devotee is not deceitful; he reveals himself honestly to the teacher or to like-minded companions; living with energy aroused for abandoning unwholesome states and developing wholesome states; being endowed with wisdom; understanding, rising, and ceasing with noble penetration; leading to the complete destruction of suffering.

Five pure abodes: the heavens called Aviha, Atappa, Sudassa, Sudassi, Akanittha.

Five classes of persons become non-returners: one who passes away before middle age; one who passes away following middle age; one who passes away with ease, without much effort; one who passes away with much effort and difficulty; one who striving goes upstream and is reborn in the Akanittha world.

Five mental blockages: here a monk has doubts about the teacher; is dissatisfied and unable to settle his mind; his mind is not inclined toward ardor, devotion, persistence, and effort; he gets angry with his companions in the holy life; he feels depressed and negatively toward them.

Five mental bondages: a monk must get rid of passion, desire, love, thirst, fever, craving for sense desires, for physical objects.

If he has eaten much and abandoned himself to the pleasure of lying down, to the pleasure of contact, of sloth, and so on.

If he is practicing the holy life with the goal of becoming a member of a body of devas, great or small, then his mind is not inclined toward ardor, devotion, persistence, and effort.

Five faculties: eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, and mind.

Another five faculties: pleasure, pain, happiness, sadness, and equanimity.

Yet another five faculties: faith, energy, mindfulness, immersion, and wisdom.

Five elements leading to emancipation: herein, when a monk is aware of sense desires, his heart does not leap forward to embrace them, nor does it rest complacently.

His heart does not wish to choose them and thus rests gratified.

His frame of mind is well balanced, well developed, well uplifted, well freed, and detached from sense pleasures.

He is freed from all the intoxicants, miseries, and fevers that arise in consequence of sense-desires. This is first deliverance.

The same becomes true when considering four other factors of ill will, cruelty, materiality, and non-self.

Five occasions of emancipation: herein, friends, when the Master or a reverend fellow-monk teaches the Dhamma to a brother monk, according to the Dhamma, the listener feels inspired, causing joy to arise. Following joy, rapture springs up. The mind being full of rapture, the body becomes tranquil. The body is tranquil, the disciple feels bliss. Feeling blissful, the mind becomes immersed. This is the first instance.

In the second instance, a monk has a similar experience—not from hearing the Master or a reverend fellow monk teach—but rather while himself teaching others the Dhamma in context and detail, as he has learned and held it in memory.

In the third instance, a disciple has an experience, not as on the first two occasions, but when he himself is reciting the doctrines in detail as he has learned it by memory.

In the fourth instance, a disciple has an experience, not as in the first three instances, but rather because he has applied thought to the doctrine as he has learned it by memory, and then sustains protracted meditation on it, contemplating it in mind

Finally, in the fifth instance, a disciple has an experience, not as on the first four occasions, but rather when he has well grasped some given clue to concentration and has then well applied his understanding, has well thought it out, has well penetrated it by intuition.

Five thoughts by which emancipation reaches maturity, in other words, the notion of impermanence, the notion of suffering in impermanence, the notion of no-self that suffers, the notion of liberation, the notion of awakening.

These fivefold doctrines have been perfectly expounded to be mindfully chanted by the sangha, in concord, for the happiness of devas and men.

References

Long Discourses, Pāṭika Chapter 33: The Recital (Sutta Central)

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

A Reminiscence About My Theravada Teachers

Nine Qualities of the Buddha

Theravada Buddhism and Teresian Mysticism: A Reflection on Interreligious Dialogue