FEATURES|COLUMNS|Theravada Teachings

On Being Mindful of the Body

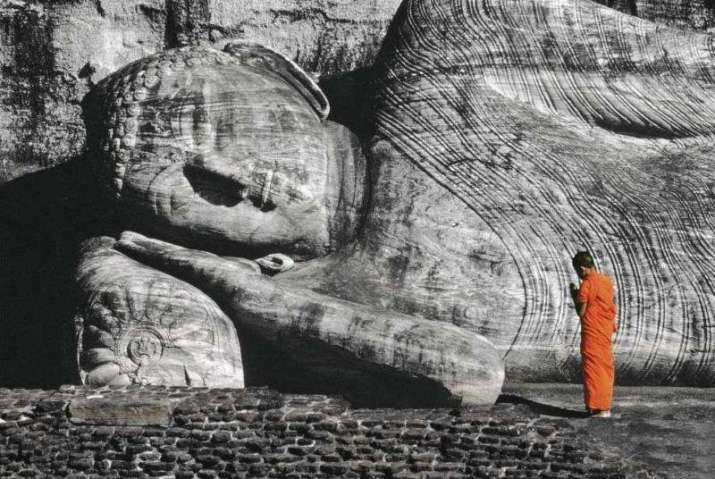

From quotesgram.com

From quotesgram.comAn effective way to disseminate Theravada teachings in English is by directly translating and quoting The Word of the Buddha—without ambiguity or speculation—and we can be grateful to Venerable Nyanatiloka Mahathera for being a master at doing exactly that.

In The Word of the Buddha (1967), Venerable Nyanatiloka translates the most significant and useful statements by the Buddha about:

Contemplation of the Body (Pali: kayanupassana)

But how does the disciple dwell in contemplation of the body?

Watching-Over In-and-Out-Breathing (anapana-sati)

Herein the disciple retires to the forest, to the foot of a tree, or to a solitary place, seats himself with legs crossed, body erect, and with mindfulness fixed before him, mindfully he breathes in, mindfully he breathes out.

When making a long inhalation, he knows: “I make a long inhalation;” when making a long exhalation, he knows: “I make a long exhalation.” When making a short inhalation, he knows: “I make a short inhalation;” when making a short exhalation, he knows: “I make a short exhalation.”

“Clearly perceiving the entire (breath-) body, I shall breathe in:” thus he trains himself; “clearly perceiving the entire (breath-) body, I shall breathe out:” thus he trains himself. “Calming this bodily function (kaya-sankhara), I shall breathe in:” thus he trains himself; “calming this bodily function. I shall breathe out:” thus he trains himself.

Thus he dwells in contemplation of the body, either with regard to his own person, or to other persons, or to both, he beholds how the body arises; beholds how it passes away; beholds the arising and passing away of the body. A body is there—this clear awareness is present in him, to the extent necessary for knowledge and mindfulness, and he lives independent, unattached to anything in the world. Thus does the disciple dwell in contemplation of the body. . . .

A body is there, but no living being, no individual, no woman, no man, no self, and nothing that belongs to a self; neither a person nor anything belonging to a person. (Nyanatiloka 57–58, 1967)

For further details about anapana-sati, see M. 118.62: Visuddhi-Magga VIII, 3. (Nyanatiloka 59, 1967)

The Four Postures

And further, whilst going, standing, sitting, or lying down, the disciple understands . . . the expressions; “I go;” “I stand;” “I sit;” “I lie down;” he understands any position of the body.

The disciple understands that there is no living being, no real ego, that goes, stands, etc., but that it is by a mere figure of speech that one says: “I go,” “I stand,” and so forth. (Nyanatiloka 60, 1967)

Mindfulness and Clear Comprehension (sati-sampajañña)

And further, the disciple acts with clear comprehension in going and coming; he acts with clear comprehension in looking forward and backward; acts with clear comprehension in bending and stretching (any part of his body); acts with clear comprehension in carrying alms bowl and robes; acts with clear comprehension in eating, drinking, chewing, and tasting; acts with clear comprehension in discharging excrement and urine; acts with clear comprehension in walking, standing, sitting, falling asleep, awakening; acts with clear comprehension in speaking and keeping silent. (Nyanatiloka 60, 1967)

Contemplation of Loathsomeness (patikula-sañña)

And further, the disciple contemplates this body from the sole of the foot upward, and from the top of the hair downward, with a skin stretched over it, and filled with manifold impurities:

“This body has hairs of the head and of the body, nails, teeth, skin, flesh, sinews, bones, marrow, kidneys, heart, liver, diaphragm, spleen, lungs, stomach, bowels, mesentery, and excrement; bile, phlegm, pus, blood, sweat, lymph, tears, skin-grease, saliva, nasal mucus, oil of the joints, and urine.”

Just as if there were a sack, with openings at both ends, filled with various kinds of grain—with paddy, beans, sesamum, and husked rice—and a man not blind opened it and examined its contents, thus: “That is paddy, these are beans, this is sesamum, this is husked rice:” just so does the disciple investigate this body. (Nyanatiloka 60–61, 1967)

Analysis of the Four Elements (dhatu)

And further, the disciple contemplates this body, however it may stand or move, with regard to the elements; “This body consists of the solid element, the liquid element, the heating element, and the vibrating element.” Just as if a skilled butcher or butcher’s apprentice, who had slaughtered a cow and divided it into separate portions, were to sit down at the junction of four highroads: just so does the disciple contemplate this body with regard to the elements. (Nyanatiloka 61–62, 1967)

Cemetery Meditations

1. And further, just as if the disciple were looking at a corpse thrown on a charnel-ground, one, two, or three days dead, swollen up, blue-black in color, full of corruption—so he regards his own body: “This body of mine also has this nature, has this destiny, and cannot escape it.”

2. And further, just as if the disciple were looking at a corpse thrown on a charnel-ground, eaten by crows, hawks, or vultures, by dogs or jackals, or devoured by all kinds of worms—so he regards his own body: “This body of mine also has this nature, has this destiny, and cannot escape it.”

3. And further, just as if the disciple were looking at a corpse thrown on a charnel-ground, a framework of bones, flesh hanging from it, bespattered with blood, held together by the sinews;

4. A framework of bone, stripped of flesh, bespattered with blood, held together by the sinews;

5. A framework of bone, without flesh and blood, but still held together by the sinews

6. Bones, disconnected and scattered in all directions, here a bone of the hand, there a bone of the foot, there a shin bone, there a thigh bone, there a pelvis, there the spine, there the skull—so he regards his own body: “This body of mine also has this nature, has this destiny, and cannot escape it.”

7. And further, just as if the disciple were looking at bones lying in the charnel-ground, bleached and resembling shells;

8. Bones heaped together, after the lapse of years;

9. Bones weathered and crumbled to dust—so he regards his own body: “This body of mine also has this nature, has this destiny, and cannot escape it.”

Thus he dwells in contemplation of the body, either with regard to his own person, or to other persons, or to both. He beholds how the body arises; beholds how it passes away; beholds the arising and passing away of the body. “A body is there:” this clear awareness is present in him, to the extent necessary for knowledge and mindfulness; and he lives independent, unattached to anything in the world. Thus does the the disciple dwell in contemplation of the body. (Nyanatiloka 62–63, 1967)

References

Nyanatiloka, Mahathera. 1967. The Word of the Buddha. Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society.

The above book is available as a free download from the Buddhist Publication Society Online Library and the Internet Archive.

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

All Phenomena Depend Upon Nourishment

Embracing the Mekong in Distress

Falguni Purnima: Celebrating Family Reunions and the Buddha’s Life