FEATURES|COLUMNS|The Five Wisdoms

The Missing Self in Buddhism and Psychology

Image courtesy of the author

Image courtesy of the authorThe big investment

A few years ago, a friend of mine was ready, along with his wife, to retire. They had invested their life savings, the work of 20 years, to fund their golden years. Unfortunately, it was with a man named Madoff. In a single moment they lost it all to this con artist and it was never recovered. What has this to do with the Dharma, mantra recitation, deity visualization, mahamudra, Dzogchen, or glimpsing the luminosity of ultimate mind? Just like that retirement fund, the Dharma requires a tremendous investment, not only of money but of precious time, effort, thought, dedication, and even sacrifice. So the question becomes, where are we really putting all this energy? Because it is not guaranteed that it will go where it actually belongs, where it can really do us some good.

Flashback to 1982, when I was first contemplating entry into a three-year Vajrayana retreat, I had wrangled the position of a driver for my teacher, the Venerable Kalu Rinpoche. Touring New York, Boston, and points between, it helped that I had purchased a black Citroen that Rinpoche would have been familiar with from his extended time in France. One day, while giving a French student a ride, I asked when he planned on undertaking a retreat, since at that time this was the logical path for Kalu Rinpoche’s students. In broken English, he spoke words that still ring in my ear: “Well, I’m not very impress with the result.”

Indeed, I have known individuals who have done six-year retreats, and Eastern lamas who have done a cumulative 20 years in caves and isolated huts, and who were variously arrogant, self-important, self-centered, vindictive, or manipulative. There are cases of people who have abandoned the Dharma altogether after a three-year retreat, while others have committed suicide. As is public knowledge—and my unfortunate personal experience—a rare few seasoned Tibetan meditators have been sexual predators or out and out thieves, even black magicians.

Yet the same teachings and practices have clearly helped transform Western Dharma students and Eastern teachers into their best selves, beacons of compassion, integrity, inner strength, and impartiality. Meditation and mindfulness can save minds, save lives, and eradicate negativity and suffering. But there are also modern mindfulness masters who are self-satisfied, arrogant, and engage in “virtue signaling” rather than actual virtue. So what gives? How can the very same Dharma produce such different results in different hands or minds? We can just shrug it off as individual differences, or karma, or pre-existing mental pathology. But there may be a more precise issue that we can put our finger on and perhaps do something about.

Unraveling a mystery

It comes back to where we invest, or “who” we are investing in; what part of us is receiving the Dharma, what part of us is penetrated by the ideas, practices, and experiences that encompass the path of Buddhism. To answer that question requires a dip into psychology, that vast repository of thinking on the nature of our relative self—not just our ultimate nature. This opens up to a much bigger issue, one central to psychology and spirituality alike, and why, in a sense, our entire culture has made a “bad investment” and continues to do so. It simply invests in the wrong self. But so can Buddhists, because both have overlooked the “missing self.” In many ways, the whole problem of humanity is a case of mistaken identity!

Back in 1982, John Welwood, a psychologist and student of Chogam Trungpa noticed a phenomenon he termed spiritual bypassing, which he defined as “using spiritual ideas and practices to sidestep or avoid facing unresolved emotional issues, psychological wounds, and unfinished developmental tasks.” This could take the form of self-inflation or deflation, specialness or self-blame. He noted, rightly, that there are two lines of human development: becoming a genuine human person versus going beyond the person altogether. Theoretically, these parallel lines of development may come to a single point on some event horizon. But staying a dysfunctional person for untold lifetimes does not seem to accelerate that theoretical convergence.

Centuries before Welwood used this term, the old Zen masters of Japan used the term “the stink of Zen” to describe those who developed a persona of specialness while taking on the external trappings and activities of a monk, but without any internal shift. Seon Roshi and others used this term freely with their Western students as clearly this problem is endemic to spiritual training. Welwood even goes so far as to call it an “occupational hazard” of meditation.

But we are still left with an unanswered question about what it means to fix oneself on a psychological level so that we can progress on a spiritual level. The growing field of Buddhist psychology may offer some solutions. But there may be an even more direct and elegant answer from an unexpected source.

Image courtesy of the author

Image courtesy of the authorThe missing self in psychology

I was always intrigued by the idea of the 25 cent gasket that disrupted the launch of a billion-dollar spaceship. The devil is in the details, and when foundational details are wrong—as anyone who has done any accounting knows—the errors carry through to all the future calculations. A few foundation blocks out of place at the bottom of our building, and that edifice can become a leaning tower of Pisa.

That was my impression of modern psychology after I came across a startling book, back in my pre-Buddhist days of the late 1970s. Within the pages of In Search of the Miraculous, G. I. Gurdjieff was quoted as saying: “Essence is the real in man, Personality is the false.” He described in detail how we have a basic nature, with its constitutional predispositions and tendencies, with our real potential, purpose, and destiny. What Trungpa called Basic Sanity or Basic Goodness is basically Essence, or is at least a core characteristic of this underlying stratum of our identity. Secondly, we develop, from an early age, a programmed, socialized, culturally molded self in order to interface with the world.

Gurdjieff termed this Personality, but to avoid confusion with modern definitions, I use the word Persona, i.e. a mask or artificial facade. Having a common interface with other human beings (including language) is essential, but it should be a vehicle or a tool of our authentic Essence. In most cases that artificial construct, with no real existence of its own, is dominant while Essence is left to wallow and wither, without nourishment. Unfortunately the whole of our modern consumer society is Persona-based, where image and impressions far, far outweigh the force of presence and being. Essence is neither promoted or supported in most cases. It is style over substance, sizzle over steak.

The conflicted selves

The Persona cannot grow and mature; it can only upgrade. A new way of speaking, a tweaked set of beliefs, different facial expressions, different emotional tones, and a new “sense of identity” can all be adopted or manufactured. Persona can have the guise of an activist, a doctor, an expert, a Buddhist. The forms are creatively infinite. Essence is that part that can grow, mature, develop, even transform. It is automatically connected to the spiritual self. And as Essence matures, it can form a True Persona, one that is fully congruent and accurately reflects who we really are, reflecting our life’s purpose and unique gifts. But it is also true that the cobbled together Persona has little or nothing in common with Essence. False Persona, once in ascendancy, is not happy to give up its artificial status. How and why we move from Essence to a Persona-based life is well beyond this short essay, but is a question that should stay prominent in one’s mind. It is the key that unlocks an understanding of the human condition.

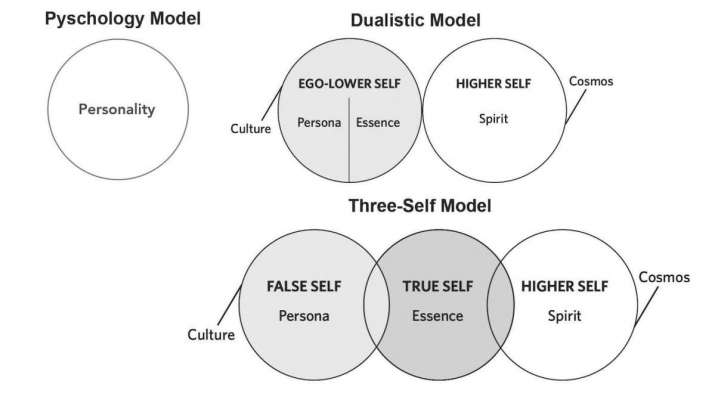

Although the idea of a True Self has not gone unnoticed by psychologists such as Rollo May, Irvin Yalom, Karen Horney, and C. G,. Jung, or some in the fields of positive psychology, social psychology, personality theory and the study of authenticity, mainstream psychology stubbornly takes the self to be one solid block. That fundamental miscalculation means that all research, reportage, surveys, statistics, and working models of traits, self-schema, self-view, developmental theory, and so on, are based on the assumption of this monolithic “personality.” This is the 25-cent part that dooms the planned interplanetary reaches of psychology. The same goes for the thriving field of self-help. But how does this impact our Dharma practice?

The missing self in spirituality

Spiritual systems in general, including Buddhism, portray a duality of mind. There is ultimate being, a non-dual, non-local luminous consciousness that underlies our limited, subject-object experience of relative reality. And then there is our familiar mundane self. Often this is identified as the “ego,” a term oddly borrowed from Freud, who defined it quite differently. As such we have a two-self system in Buddhism (or you can call it a self and non-self system). Ego is the tyrant who usurps our spiritual self, the “narrow cell of your false identity.” It obscures our Buddha-nature, the spacious consciousness that transcends this localized identity. Yet we know our state can vary from mechanical, unaware sleepwalking through life, to an awakening, highly attuned awareness of ones own being and the vibrant world around us. Something big is lost when we lump everything about our normal state together and pathologize it. And something bad happens when we think we have to transcend, eliminate, or leap over that self. Because there are two very different creatures living in that egoic self: Essence and Persona. Essence is the bridge to the spirit.

Diagrammatically, it looks like this:

Image courtesy of the author

Image courtesy of the authorThe next step

Spiritual bypassing, and the stink of Zen, are both instances in which the Dharma enters Persona, but does not penetrate Essence. There is a third self, neither “ego” nor pure luminous consciousness, which if ignored, hobbles both modern psychology and Buddhism from fulfilling their grand promises. Indeed, it appears that becoming Essence-centered is the only healthy way toward spiritual development. Trungpa, Welwood, and thousands of other teachers have ways of helping drop down into Essence temporarily. If this mechanism was better understood, we would have a much better chance of living there. So does your Dharma practice enter Persona . . . or Essence?

References

Farias, M., and Wikholm, C. 2015. The Buddha Pill: Can meditation change you? London, England: Watkins.

Horney, K. 1950. Neurosis and human growth. New York: W. W. Norton.

Kalupahana, D. J. 1987. Principles of Buddhist psychology. New York: State Univesity of New York Press.

May, R. 1983. The discovery of being. New York: W. W. Norton

Lerner, Melvin J. and J. J. Clarke. 1994. Jung and Eastern thought: A dialogue with the Orient. New York: Routledge.

Millon, T. and M. J. Lerner. 2003. Handbook of psychology. vol 5: Personality and social psychology. Hoboken, N.J: John Wiley & Sons.

Ouspensky, P. D. 1949. In search of the miraculous. New York: arvest Books.

Peterson, C. and M. Seligman. 2004. Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Trungpa, C. 2010. The sanity we are born with: a buddhist approach to psychology. Boston, MA: Shambala.

Wood, A. et al. 2008. The Authentic Personality: A Theoretical and Empirical Conceptualization and the Development of the Authenticity Scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology American Psychological Association.(55) 3, 385–99

Walter, P. F. 2015.The Ego Matter: About The Importance Of Autonomy For Realizing Your True Self. Newark, Delaware: Sirius-C Media Galaxy.

Yalom, I. 1980. Existential Psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books.

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Practicing the Bodhisattva Path with Buddhism and Psychology: An interview with Ven. Zhankong

Buddhist Psychology for the Modern World: An Interview with Lene Handberg

Spiritual Bypassing and the Dangers of Unresolved Emotional Wounds