B. Alan Wallace: In Buddhism, our challenge is to respond to whatever arises to us, whether we regard it as felicity or adversity, good times or bad, and transmute everything that comes our way into our spiritual practice to make it meaningful. So this is indeed a challenging time, but when we look back on human history, when was there not a challenging time, at least for some very significant portion of the human population? These are difficult times medically, but only a small fraction of the human population has been directly influenced by this virus; millions and millions more are influenced by it financially, in terms of their livelihoods. Their sense of security is lost and they wonder whether they can find their next meal, or take care of their families. How do we transform this? If we look at this from a really deep perspective, this pandemic didn’t come out of nowhere.

I’ve read account after account saying that we human beings have created the circumstances that brought this upon us. We are violating our environment; we are violating other species; we have wiped out half of the wildlife on the planet over the last 40 years. We have brought more destruction on the ecosphere than at any time since the great meteor hit some 65 million years ago. We are experiencing now the results of our own actions, even without alluding to the Buddhist view of karma, which I do indeed accept. Karmically speaking, from lifetime to lifetime we’ve actually brought this upon ourselves. So how can we transmute it? Number one, we have to wake up, all of us 7.8 billion people. We have to be aware of how we, collectively, are violating the environment that is not only our home but the home of 20 billion, billion animals with whom we share this planet. We must treat this environment gently, lovingly. We must look forward 10 generations ahead to see that we leave this Earth in better condition than it was when we first arrived. But right now we are, of course, doing the exact opposite.

So we are experiencing the harvest of the seeds we have sown—we, collectively. Especially the rich nations; the nations that pride themselves on an ever-increasing gross domestic product, as if the more you can consume, the more you produce, the more successful your society is: this is an insane notion. We see how much suffering is going on every day. We attend to it, it invites us to think outside of our own shells and attend to humanity, attend to this whole world of sentient beings on our planet, and arouse compassion, compassion for those who act out of delusion and ignorance, out of short-sightedness and greed, and sometimes, out of anger, hatred, jealousy, and racism. So it is a time to transform, to withdraw temporarily from our active lives into simplicity, into solitude, and ask the deeper questions: How can we lead the most meaningful lives possible, individually and collectively? How can we cultivate greater compassion by witnessing suffering and seeing that there is, in fact, a way out?

Wallace listening to His Holiness the Dalai Lama at a Mind and Life Conference in 2004.

From mindandlife.org

BDG: Please tell us about the Santa Barbara Institute for Consciousness Studies’ latest project, the Center for Contemplative Research (CCR), which is under development on a what was previously a Christian hermitage near the town of Crestone, Colorado. What will be the purpose of this center?

BAW: The center is 110 acres [44.5 hectares], and already has 11 retreat cabins on it. It has a chapel, a meeting hall, and has great potential for building more cabins to further develop this facility, which for the last 35 years had been a Carmelite hermitage. By 24 July, we will have finished the purchase and very swiftly will fill the 11 cabins with people dedicated to full-time contemplative practice for months or even years on end. But this is not just for our own sake, not just for each individual who comes here.

In addition to the initial 11 cabins, we would like to have up to 32 and be able to hold shorter retreats as well. This will be a place for people to receive long-term, full-time professional training to purify their minds, to develop compassion, to develop wisdom and insight. This begins with making the mind serviceable, really purifying the mind, developing mindfulness, introspection, concentration, and developing attention skills. We will be working, when the time is ripe, with neuroscientists, psychologists, possibly people in the field of education, in mental health, and with physicists, as well to trying to fathom the nature of the mind and its role in the universe. Modern science has been looking in the wrong direction in the last 110 years, ever since behaviorism took over academic psychology in about 1910. We have been looking outward, to the brain, to behavior, asking other people about their experiences when if you want to fathom the mind, like any other natural phenomena, you need to look at it. And you need to develop the skills to look at it, with continuity, with rigour, with precision, and without superimposing our experience, our own preconceptions, our fixations, and our closed-mindedness.

Retreat center (Miyo Samten Ling) in Crestone, Colorado. Photo by Eva Natanya

We should be looking inward, cutting through the limitations of the human mind to a more fundamental continuum of consciousness that transcends the configuration of the human mind arising in dependence on the brain. Beyond this dimension of individual primal streams of consciousness, we should be looking yet deeper, beyond individual consciousness, cutting through to the dimension of consciousness we call buddha-nature, the tathagatagarbha, the dharmakaya, the mind of the Buddha, which is non-local, atemporal, utterly transcendent, and is the ultimate wellspring of genuine wellbeing, of all virtues and all wisdom and compassion. We are here to know who we are, and the way to know who we are is by looking within. So this is the purpose of creating this Center for Contemplative Research. We will start by focusing on the practices with which my colleagues and I are most familiar, stemming from the Buddhist tradition. But the Dalai Lama himself also encourages us to reach out and open up dialogue in collaboration with the Christian tradition, as well as engaging in collaborative research with scientists.

BDG: How is the Center for Contemplative Research connected with the Shamatha Project held in 2007? Why focus on the achievement of shamatha?

BAW: The Shamatha Project held in the Rocky Mountains entailed two three-month retreats with a total of 70 people in two groups of 35. We focused on shamatha, which refers to a range of practices designed to achieve samadhi—highly focused, stable, sharp, clear, vivid attention. Like developing a telescope to explore celestial phenomena, shamatha is like a telescope for exploring the mind.

We also complemented the training of attention with cultivation of the heart. This was through the cultivation of the four brahmaviharas, the four divine abidings, which are also called the Four Immeasurables: loving-kindness, compassion, emphatic joy, and impartiality. These were the two themes—cultivating attention and cultivating the heart, bringing these two together—and people found this immensely meaningful. The scientific study itself was a terrific success. They have already published 13 scientific papers and more are coming. By and large, everyone at that retreat said it was the most meaningful three months of their lives. Given the inspiration of that, I thought wouldn’t it be wonderful to do something more than a three-month project? We had just partaken of something like an hors-d’oeuvre. Why not go further and create facilities where people can engage in such foundational meditative practices, developing attention and mindfulness, introspection, and cultivating the heart in ways that are open to everyone? You don’t have to embrace a Buddhist worldview, believe in karma, reincarnation, Nirvana, and so forth, in order to train the mind with shamatha, to cultivate these four sublime virtues of the heart. They are open to everyone.

This was the major reason I chose these two modes of meditation—shamatha and the Four Immeasurables—for scientific study. They are open to anyone, Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Taoist, atheist, and agnostic. So now we want to develop this center for contemplative research on that basis, a place where people can come to receive such full-time, professional training in contemplative practices. We are trying to keep the overhead as minimal as possible so that for months or even years they can be trained as professional contemplatives.

Throughout the history of Buddhism, everywhere Buddhism has flourished—India, Southeast Asia, East Asia, Central Asia—there have always been people, men and women, who devoted themselves full-time, for life, or at least for years or even decades, to full-time professional contemplative training, and these are the ones who became the brightest lights, who fathomed the meaning of the Buddhist teachings: the reality of suffering, the source of suffering, the possibility of freedom, and the path to such freedom. This is the purpose of this center—to focus on the foundational practices, bringing in science, so that the contemplatives are actually collaborating with scientists and not simply be studied by scientists. This will be unprecedented, without parallel, to have professionally trained scientists collaborate with professionally trained contemplatives, working together from the outside in, and the inside out to fathom the nature of mind, the origins of mind, what happens at death, the causes of mental distress, and the inner causes of genuine well-being—the type of well-being that can be sustained through all the vicissitudes of life including pandemics, and all the challenges that lie in wait for us in human civilization over the coming decades.

BDG: You had planned a long program of courses and conferences around the world this year that have had to be canceled as a consequence of the pandemic. I am particularly interested in a scheduled event that I now see is taking place online. The annual retreat at Lampeter Campus, University of Wales, will be replaced by an online retreat conducted by yourself and Dr. Eva Natanya from 18–23 August, titled “Dwelling in the Heart of Reality: Parallel Practices in Buddhist Dzogchen and Christian Mysticism.” How can we make sense of the structural affinities and phenomenological similarities between the two religious systems, notwithstanding their undeniable differences?

BAW: Certainly, having been raised as a Christian—my father is a Christian theologian—I am familiar with the profound differences between the Christian worldview and practices and those of Theravada Buddhism, Indian Mahayana Buddhism, Vajrayana, Chan, Zen, Dzogchen, and Mahamudra. They are certainly very different. Fifty years ago, I read Aldous Huxley’s book The Perennial Philosophy, in which he proposed that if we look at the world’s great religions and within them their contemplative traditions—if we go deep into the experiences themselves among the greatest adepts of Buddhist contemplative practices, and Christian, and Taoist, and Hindu and so forth—there is a convergence on a common reality, “one reality” that transcends the methods and ideologies that are the framework in which these contemplative practices are cultivated. So the notion of there being a “perennial philosophy” of reality, a transcendent reality that is unitary, to which all the great religious traditions, the great wisdom traditions of the world converge, has been a working hypothesis of mine for the last 50 years. Over that half century, I’ve focused on the wisdom tradition of Buddhism because this is the one where I feel at home, it speaks to my heart and mind. But I do come from a Christian background.

As I was researching my book Mind in the Balance: Meditation in Science, Buddhism, and Christianity (Columbia University Press 2009), I was struck by the fact that when we explore the writings of the early desert fathers, through the Greek Orthodox tradition of contemplative practice, as well as the Neo-Platonic tradition from John Scotus Eriugena in the eighth century right on to the 15th century Nicholas of Cusa, there is a resonance between these teachings, and those of Dzogchen—the Great Perfection tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. I found this quite remarkable and worth writing about. Yes, the context of Christian theology and the context of the Buddhist teachings—the Four Noble Truths, the perfection of wisdom of the tathagatagarbha—are certainly very different. But when we go right to the practices themselves and the insights which emerge from them, I found very, very provocative common ground.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama, who is my primary spiritual mentor and guide, emphasizes that we look above all for the common ground that binds us together, that unites us among the diverse religious traditions of the world, acknowledging the differences, even celebrating the differences. As his Holiness points out, the religions of the world are here to help us overcome the afflictions of the mind, overcome suffering, cultivate compassion, loving-kindness, wisdom. Let us look for the common ground, highlight the common ground, while recognizing the differences. We do this in theory and practice, encouraging people, those who participate, to check out for themselves, as we see in the Pali Canon of the Buddhist tradition, “ehi pasi,” meaning “come and see for yourself.” Are there genuine common grounds between these traditions, or just something we are imagining? This is to be seen through our own experience and collaboration with fellow contemplatives from different traditions.

BDG: You have been closely connected for many years with the Benedictine monk Father Laurence Freeman, director of the World Community for Christian Meditation. Tell us about your dedication to developing a dialogue and joining bridges between different wisdom traditions.

BAW: I have known Father Laurence Freeman at least since 1999 in a lovely meeting in the little village of Prato in Italy, where the Dalai Lama came and we had a few days of Buddhists and Christians coming together to discuss how we can understand the interrelationship between these two traditions. Before I arrived, I was expecting that we would see the Christians on one side, with Father Laurence Freeman and his followers wearing white; His Holiness, being a Tibetan Buddhist monk, would be wearing burgundy, so we’d see the red side over on the other side. These two different groups were not of course all wearing these colours, but metaphorically I imagined they would be two quite distinct groups. But when the conversation unfolded, we saw that it was not just white and red, it wasn’t just Christians and just Buddhists, but rather shades of pink. The Christians who showed up were genuinely interested in learning from Buddhism, not trying to convert the Buddhists over to Christianity; and of course the Buddhists did not come to convert the Christians, but to learn from Christianity, to see how we can learn from each other. I remember this vividly.

I have met Father Laurence a number of times since; we’ve done workshops together in Santa Barbara and in London. We recently had an online conversation last March with my colleague Eva Natanya, who is both a Buddhist and Christian practitioner. I was quarantining myself at the time in Crestone at the hermitage that we are about to buy. So a meeting that we planned to take place in person at the Benedictine center that Father Laurence has created in France took place online instead. Father Laurence and a small collection of his students were gathered at his center in France, while Eva and I joined them online from Crestone. It was lovely, learning from each other. There was a sense of humor, humility, respect, warmth, and affection. We saw that we had much to learn from each other. Each of these traditions has its own strengths, each of course has its limitations. How could they not? So we came there to learn from each other and this dialogue continues.

B. Allan Wallace, Eva Natanya, and Father Laurence Freeman attend an online dialogue

about the mystical traditions of Buddhism and Christianity.

Image courtesy of the Bonnevaux Centre for Peace

There are many interfaith meetings, and books, and so forth, and these are very worthwhile. But I think we can go further. There have been many scientific studies of the brains and behaviors of meditators, in which the meditators are subjects of the scientists. But we are moving beyond that in our center. We are having contemplatives collaborate with the scientists. So the scientists will learn from the insights of the contemplatives, and the contemplatives will learn from the insights of the scientists. This will be true collaboration, not just scientists studying subjects. Likewise, contemplatives will meet with contemplatives from other traditions, sharing their experiences and not just talking about their doctrines, ideas, beliefs, institutions, rituals. All of these have their place. I am not disparaging any of them, but what is most important is the inner transformation, the inner liberation, the salvation, the freedom, the cultivation of wisdom and compassion, and the alleviation of the inner causes of suffering for ourselves and those around us. It is time for a major shift, such that the religions of the world come together in a spirit of humility, wishing to learn from each other, and wishing to heal this planet. We need scientists and people of all faiths, and also people with no religious faith, with good hearts. That is what I would like to share with you today.

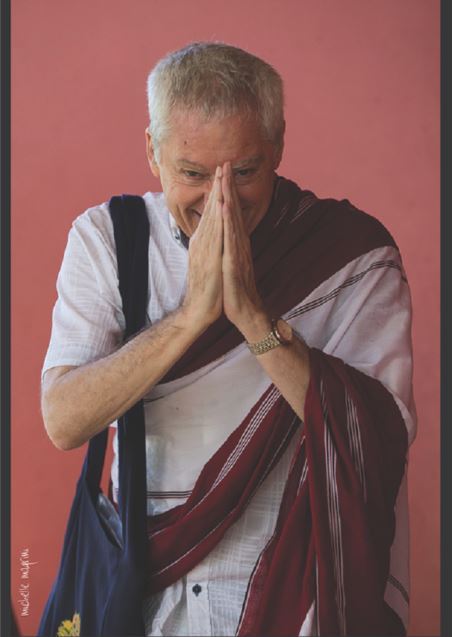

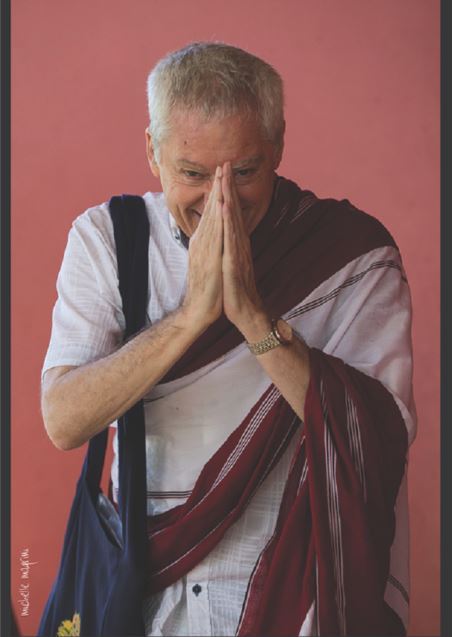

B. Alan Wallace. Image courtesy of Michelle Magrini

See more:

The Center for Contemplative Research in Crestone, Colorado (Santa Barbara Institute for Consciousness Studies)

Center for Contemplative Research

Lampeter 2020 Virtual: A Retreat with Lama Alan Wallace and Dr. Eva Natanya (The Contemplative Consciousness Network)

Authored Books (B. Alan Wallace)

Online teachings from Alan Wallace (The Meridian Trust)

Conversations with B. Alan Wallace (MIT Media Lab)

A Wisdom event with Alan Wallace, Shamatha: Meditation for Balanced Living (YouTube)

Alan Wallace's teaching on Dzogchen at the Gomde Retreat (YouTube)

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Contemplative Practices: Helping Children Enjoy Meditation

Theravada Buddhism and Teresian Mysticism: A Reflection on Interreligious Dialogue

The Wild Geese of Buddha and Christ

The Way of Ordinary Life: An Interview with Karen Maezen Miller

Science Meets Mind - Imagining a Revolution, with B. Alan Wallace

Curiosity and Doubt: The Spiritual Career of Judith Simmer-Brown

Buddhistdoor View: Conscience in the Thought of Bhikkhu Bodhi