FEATURES|THEMES|Mindfulness

Mental Interplay: Venerable Analayo on Mindfulness and Memory

From Buddhistdoor Global

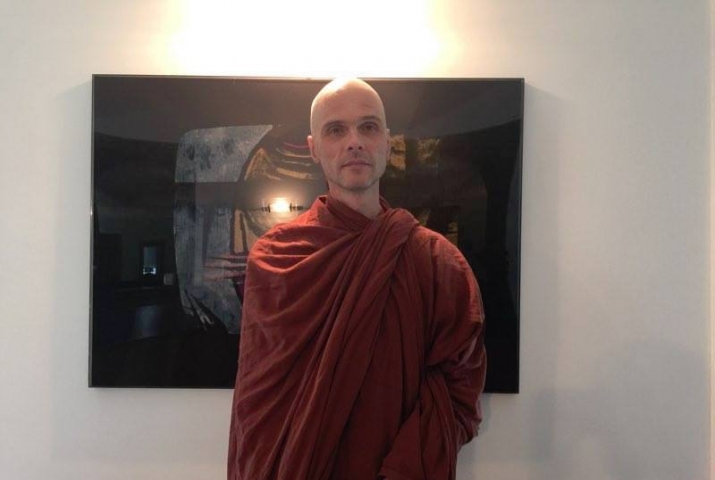

From Buddhistdoor GlobalVenerable Analayo is a sharp and perceptive monk. An active campaigner for bhikkhuni ordination, he is one of the most important Buddhist intellectuals in the field of Pali Studies today. Although I have corresponded with him for several years, I met him in person for the first time only in May, in the lobby of the Ateneo Garden Palace Hotel in Rome. We had both flown in to attend the Second International Conference on Mindfulness at Sapienza University, at which Ven. Analayo gave a keynote speech on 11 May. Such is the German monk’s linguistic ability that when his Italian translator struggled to articulate some of the more specific and dense Buddhist terms in psychology and philosophy, the multilingual monastic simply took over and spoke in Italian.

Ven. Analayo’s main objective in his keynote speech was to discuss the role of mindfulness (P. sati) in various contexts. The Theravada master explained his conceptual understanding of mindfulness: “Mindfulness is all about being aware, open, and receptive to what is happening in the present moment, with what happens right here and right now, and in this way it’s established only by staying with the here and now even as it assists us in remembering the past. Mindfulness can come in wholesome and unwholesome forms. Mindfulness that is aware of dukkha [‘suffering,’ or ‘dissatisfaction’], that is aware that I make contributions to it, and that aims at the diminishing of dukkha, is correct mindfulness. But think of the sniper. He’s mindful, but his intention is harm. And he’s not aware of the Four Noble Truths or practicing them, so that’s wrong mindfulness. As many Buddhist practitioners have pointed out, it’s very important to be aware of the ethical context.”

The Four Foundations of Mindfulness—awareness of the body, feelings, one’s state of mind, and moving towards liberation—imply the importance of being aware of prominent feelings in reducing suffering. Ven. Analayo went on to unpack them: “Suppose you ask me some question that in some way hurts my ego. The very first thing that comes will be an unpleasant feeling that I can sense. After this feeling, I will think to myself, ‘Who does Raymond think he is? How dare he? Now I’m going to refute him.’ And if I’m just aware of these thoughts, I can be aware of the reaction right when it starts and nip it in the bud. I can say to myself, ‘Hey, there’s a prominent feeling here—let me just have a quick look at my mind, let me see if there’s conceit or anger building up.’

“Mindfulness helps me do this even when the prominent feeling has intensified, when I can get this internal feedback and analyze my own thoughts: ‘Why are you thinking like this, Analayo? Am I really correcting or talking with Raymond with just the wish to share Dharma? Or is there some ego that wants to prove something?’” The same kind of awareness would nip in the bud any pleasant thoughts born of ego in response to praise or flattery.

Ven. Analayo’s keynote speech also examined the relationship between mindfulness and memory. “The challenge is that the word sati is sometimes used for ‘remembering’ [an association that has antecedents in the Vedas],” he said, quoting a passage in the Satipatthana Sutta: “ ‘Somebody is mindful with supreme skill in mindfulness, recollecting, remembering, what has been said long ago, what has been done long ago . . . ’ Some of my colleagues have said that mindfulness is a form of memory, but this doesn’t work.”

He was referring in particular to Ven. Thanissaro, another respected Theravada scholar, who argues that mindfulness is a process of bringing memory to bear on the present moment (Thanissaro 2012, 150). According to Ven. Analayo, this is a misunderstanding arising from a conflation of mindfulness and perception (to which memory belongs, according to Buddhist thought).

He proceeded to enumerate various kinds of memory, which he has elaborated further in a forthcoming paper. “Semantic memory, which is facilitating our communication in English, can be drawn upon even when we aren’t mindful—no one forgets the language they are communicating in—so it can’t be equated with mindfulness.” The same, he argued, goes for episodic memory, which refers to specific events, such as a recent dinner with friends or a holiday. Those who agree with Ven. Thanissaro’s argument would assert that the ability to remember many past events was an indication of mindfulness, but Ven. Analayo brings up the example of a meditator whose mind wanders to a memory of an event that occurred years or months ago. This unintentional dwelling on memories of the past indicates episodic memory that is incompatible with being mindful. Nor can mindfulness be equated with working memory, which is short-term memory concerned with immediate conscious perceptual and linguistic processing. One example would be a speech I’ve memorized, a joke, or rehearsed lines for a performance, only to lose my train of thought halfway through and, for the moment, struggle vainly to remember what I intended to say.

“My solution is that mindfulness can’t be equated to memory, but mindfulness enhances memory,” Ven. Analayo concluded, in that the presence of mindfulness makes it easier to remember things. This clarification of the relationship between mindfulness and memory is extremely important because it makes it clear that mindfulness is not to be equated with memory as per Ven. Thanissaro’s interpretation, while maintaining the apparent and unique link between the two. Ven. Analayo went on: “The correct definition is absolutely crucial because an incorrect association of mindfulness as memory has led to very dubious practice and results in mindfulness teaching.”

Ven. Analayo advocates mindfulness as a tool to help us store information in our memory bank and to draw on it at later periods (because mindfulness enhances memory, we are less likely to have a distorted or biased picture of the past). I also feel our spiritual practice would be enhanced and amplified if we were to apply a correct understanding of mindfulness to wholesome mental content—although this is a different emphasis that requires further dialogue between clinical therapists and Buddhist masters. Memory is an omnipresent part of our lives, and we often live in its shadow with little impetus or opportunity to analyze it critically. But for Ven. Analayo, a correct understanding of the relationship between mindfulness and memory can lead to immense benefit for practitioners.

References

Bhikkhu Thanissaro. 2012. Right Mindfulness, Memory & Ardency on the Buddhist Path. Valley Center: Metta Forest Monastery.