Metta, Tried and Tested

By Mettamorphsis

Buddhistdoor Global

| 2019-04-04 | Welcome to the latest metta experiment of the Living Metta laboratory that is taking the generation of metta off the meditation cushion and out into everyday living. In my last article, When Metta’s Just The Ticket, I shared a heart-centred experiment inspired by Amma, the Hindu hugging saint. This month’s experiment heads into more academic territory.

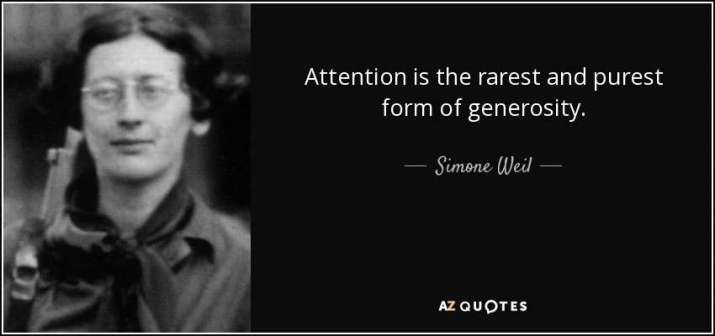

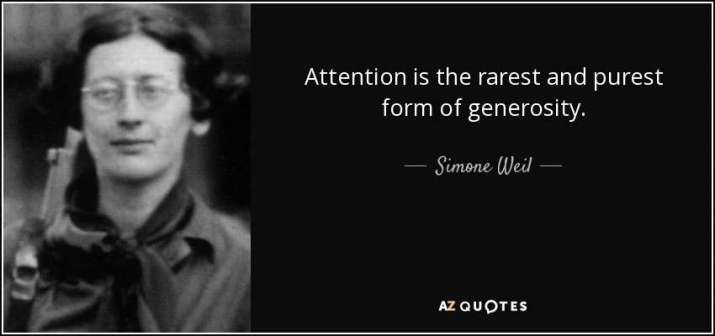

A few years ago, while housesitting in Kent, I related some of the casual work I did during my years of lilypadding—combining meditation practice and location-independence as described in my previous Lily Pad Sutra column—to an Irish friend who is both a no-nonsense IT tutor and Catholic spiritual director. She commented wryly that I could teach Madonna (the singer) a thing or three about reinvention, and that my stories brought to mind Simone Weil, a 20th century French philosopher, political activist, and Christian mystic.

Simone Weil. From wikipedia.org

Simone Weil. From wikipedia.orgAlthough much admired during her lifetime by radical political thinkers, Weil only really came to the world’s attention a decade after her death through her books and notebooks. While many may disagree with the extremism of her ideas, no one can fault her dedication to them.

For example, rather than theorize about the situation of the working class, she worked undercover for a year at a Renault car factory and as a farm laborer. To show solidarity with everyday German citizens during World War II when she herself was safely living in England, she ate only as much as they were allowed under rationing. She died of self-starvation in 1943, aged 34.

Weil fascinates me personally for being the most cerebral example of altruism I’ve come across, and for just how far her altruism continues to ripple long after her death. Feminist writer Simone de Beauvoir was a university friend, and said of their first meeting at age 18: “I envied her for having a heart that could beat right across the world.” (Hellman 1983)

Existentialist writer Albert Camus described Weil as “the only great spirit of our times,” and even meditated in her former rooms before going to Stockholm to receive his Nobel Prize for Literature in 1957. (Hellman 1983) American singer and “punk poet laureate” Patti Smith considered visiting Weil’s grave in Ashford, Kent, as a pilgrimage: “I marvelled as I traced Weil’s path through the halls of higher learning, rumination, revelation, revolution, and higher sacrifice.” (YaleNews) And Weil’s name is often mentioned in the current media commentary of France’s Yellow Vests Movement.

My personal favourite description of her comes from philosopher Gustave Thibon: “I will only say that I had the impression of being in the presence of an absolutely transparent soul which was ready to be reabsorbed into original light.” (Perrin & Thibon 2004)

In January, my agency work turned me into a university exam invigilator for a fortnight. I turned up on the first day with an open mind, curious how living metta might play out in such a silent and cerebral setting in contrast to the loud and chaotic hospitality settings I’d been sent into so far.

Watching the 360 empty desks slowly fill up with anxious undergraduates twice a day for the morning and afternoon exam sessions unexpectedly brought to mind the many 10-day Vipassana meditation courses I had sat and later managed. However, rather than sitting to empty their minds (paradoxically called mindfulness), these particular students were desperately trying to keep their minds full! And, facing hundreds of anxious faces, I defy anyone to remain nostalgic about being young. Self-compassion had clearly been left in their rucksacks along with their mobile phones and textbooks.

While I silently generated metta for the palpable panic in the room, I observed that invigilating itself very quickly brought to the surface the best and worst in my co-workers. Otherwise pleasant strangers suddenly became prison wardens under exam conditions—almost as if they were giving in to the collective self-hatred in the exam hall—while others became compassion itself.

The most compassionate was a petite woman in her late 60s with flaming red curly hair: she was exquisite to watch gently walking up and down the aisles, patiently answering the same whispered nervous questions over and over.

During our lunch break, I discovered that she was a mother of eight and grandmother of 25. I couldn’t resist asking her her secret for remaining so unflappable. Her answer? Treat everyone anew. What works for one child or student won’t work for another. In her experience, the best invigilators were good at doing nothing. Interestingly, those observations answered another unasked question of mine: the least compassionate of our co-workers were the ones who were treating all the students alike and were unable to sit still, i.e. do nothing.

From bennewmark.wordpress.com From michelle-maclean.com

Similar to 10-day Vipassana meditation courses, exams also have their version of bolters—students unable to remain in the hall because they feel overwhelmed. For the first half hour of an exam, students aren’t allowed to leave the hall to give latecomers a chance to arrive. Once those 30 minutes are up, hands start to go up requesting toilet breaks. An invigilator escorts each one to ensure that they don’t speak to anyone or secretly access reference materials. Some, intent on not wasting a single minute, literally ran to the toilet and back once we’d exited the hall. Others would dawdle as much as possible.

One young woman I escorted was visibly shaking the closer we got back to the exam hall doors. Sensing she might need a little more time, I asked her to sit down on a bench with me and take a few calming breaths. Out tumbled the pressure she was under not only from herself, but her family, and how she’d spent the night vomiting and having panic attack after panic attack.

From psycom.net From pixabay.com

I nudged her out of the building for some fresh air, and let her tell me all. Once she’d spoken her piece with tears of absolute self-hatred streaming down her face, I gently asked her: “Do you want to know what I think?” Surprised to hear my voice and its direct question, she nodded yes. “I think you’re the bravest student in that room. While you are up against all of what you just described, you still turned up. That’s bloody, f*cking amazing!” I added there was no need to torture herself further that day, and that there was absolutely no shame (or academic penalty) in opting to resit in the summer. I then got her lecturer out of the exam hall to say it again with less color and more academic authority. As he spoke, her shoulders relaxed, her breathing steadied, and I quietly went in to fetch her things still inside the exam hall so she could go to the student welfare office and speak further with a counselor about her panic attacks.

Nerves can take other forms too.

Minutes before another exam was due to start, a co-worker flagged me to say she thought she’d seen writing on a student’s hand and asked me to double-check. I quickly went over and asked the young woman to show me her palms. She only showed me one. When I motioned to see the other, she reluctantly opened it to reveal it covered in handwriting. Looking her in the eye, I could see all of the same panic and pressure of the previous bolter, and in response I grabbed her drink bottle, handed her a tissue, and whispered that if she wiped the writing off that instant I wouldn’t report it. She gratefully took up my offer, and I hope she did better than she was expected by trusting herself instead of cheating.

From knowledgeplus.nejm.org From compassioninspiredhealth.com

Every few days over that fortnight, I was asked to help with special adjustments. These are exams-for-one, tailored according to individual needs such as a broken arm or high anxiety or blindness. These students usually get an extra 15 minutes per standard exam hour, and an option to stop the clock for 15 minutes on the hour as well (minutes which then can be added on to the overall exam time).

Usually, it’s obvious what’s needed from an invigilator when you meet a special adjustment student. However, one young woman I was partnered with simply looked like she’d pulled an all-nighter in preparation. When I discreetly asked how I could make the exam easier for her, she laughingly exclaimed: “Keep me awake!” If you’ve ever managed a meditation course, you’ll remember that after chasing down bolters from the hall, the next biggest challenge is nudging nappers awake without touching them.

It turned out this particular student had narcolepsy and, for the next three hours, I sat beside her and quite literally kept her awake by tugging on her sleeve whenever her eyes drooped. It’s comic as an anecdote but, by the end of three hours I could only imagine how challenging day-to-day life was for her: her stop-the-clock was 24/7, and her world was anew every few minutes!

As we exited the building together, I asked to hear more. She described the hilarious and hurtful situations of a condition she’d had since birth, the hardest of which was facing others’ assumptions as—unlike epilepsy’s dramatic seizures—her “naps” looked like laziness or drunken/drugged states to strangers. In awe of her equanimity and wisdom-beyond-her 19 years, I told her about an older friend I had with narcolepsy who’d been a business woman (whenever her staff couldn’t find her in the office, they could usually find her asleep under the boardroom table!) and a mother of four. This cheered the young woman on as she’d not met another narcoleptic and was beyond tired of others’ limiting beliefs.

So, my fellow metta-scientists, this month I’ll urge you to stay vigilant: stop the clock on any self-hatred you encounter and give self-compassion extra time instead. Or, to metta-morphose my favourite Simone Weil quote:

Metta is the rarest and purest form of generosity.

From aquotes.com

From aquotes.com