FEATURES|COLUMNS|Coastline Meditations

Guilt: a Hindrance or a Gift?

From mindworks.org

From mindworks.orgWhen it comes to unpleasant feelings, I can say without a doubt that my least favorite is guilt. Sadness, anger, and fear are all worthy contenders, but to me there is nothing worse than waking up blissfully only to remember moments later that I have contributed to the misfortune of another being. Now, as the Vietnamese Buddhist teacher and author Thich Nhat Hanh puts it: “We have all made mistakes in the past.” (Thich Nhat Hanh 1990, 110)

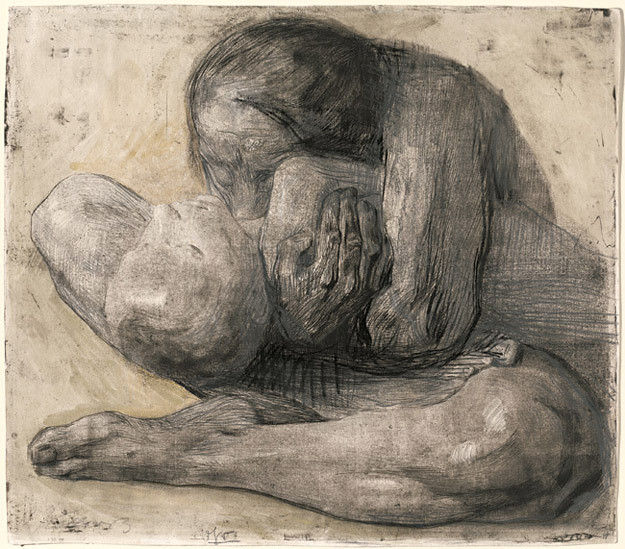

Most of us have also, therefore, experienced the highly unpleasant feeling of guilt* that often accompanies wrongdoings. Consider, as does Thich Nhat Hanh, the case of a person who has mindlessly caused the death of a child. More often than not this would result in overbearing feelings of remorse. So I wonder, is such a person doomed to eternal self-reproach, or is there a chance of liberation?

In his book Transformation and Healing, Thich Nhat Hanh explains that it can go either way. He writes: “In Buddhist psychology remorse or regret (Skt: kaukritya) is a mind function which can be either beneficial or damaging.” (Thich Nhat Hanh 1990, 110) The book is a commentary on the Satipatthana Sutta,** also known as The Sutra on the Four Establishments of Mindfulness. The Satipatthana Sutta is from the Pali Canon and offers one of the Buddha’s most detailed instructions on meditation, at the heart of which is sati, which Thich Nhat Hanh translates as “to stop” and “to maintain awareness of an object.” (Thich Nhat Hanh 1990, 35–36) The sutra tells us to look deeply—mindfully—into the nature of all phenomena. This is also true when dealing with remorse, as indicated in the following passage:

When agitation and remorse are present in him, he is aware, “Agitation and remorse are present in me.” When agitation and remorse are not present in him, he is aware, “Agitation and remorse are not present in me.” When agitation and remorse begin to arise, he is aware of it. When already arisen agitation and remorse are abandoned, he is aware of it. When agitation and remorse already abandoned will not arise again in the future, he is aware of it. (Thich Nhat Hanh 1990, 110)

Having such an aversion to guilt, I find it very difficult to practice in this way. I usually try my best to avoid the feeling and on the rare occasion when I do decide to observe it, I am completely overwhelmed by its presence. In Full Catastrophe Living, MBSR*** creator Jon Kabat-Zinn describes the haunting tendency of difficult emotions such as guilt: one tends to ruminate over an event already passed, wishing things had happened differently or that one could turn back the clock to rectify the mistake. In the example of a person who is responsible for a child’s death, they may constantly relive the event and fantasize about what could have been done to avoid the misfortune. The result of this tendency, Kabat-Zinn explains, is that we become “cut off from our ability to see clearly and to heal just when we need it the most.”(Kabat-Zinn 2009, 415) Remorse or guilt is an obstacle to our practice, and it is likely to result in making more mistakes.

There is, however, another option available to those who seek liberation. As Kabat-Zinn explains: “How much healing takes place after the devastation depends on how much you are able to be awake, face its energies, and observe with wise attention while they are raging.” (Kabat-Zinn 2009, 416) Here the author is alluding to the power of mindfulness. We are encouraged to look deeply into the nature of things, to observe emotional suffering as it arises and ceases to exist, again and again. This can be very unpleasant and scary. Truth be told, when observing these feelings I have often felt so nauseous that no sooner than have I sat down on my meditation cushion, I am back up again!

Yet it is only when we are willing to practice in this way that we are able to experience interbeing, and this is when true healing happens. According to Thich Nhat Hanh, by cultivating skillful virtues in the present we are able to reach past and future generations. Our mistakes can be undone “because as we transform the present, we also transform the past.” (Thich Nhat Hanh 1990, 110–11) As an example, he emphasizes the fact that there are many unfortunate children in the world who are suffering. Instead of drowning in guilt, a person who has previously cost the life of another being (or child) can save the lives of others—such as other suffering children. In this way, remorse can be transformed and we are able to contribute to the betterment of society.

We have all made mistakes—whether it a careless remark said during a drunken night out, or a crime that has cost another being’s life. May we all find the courage to carry on with our practice.

* Here guilt and remorse are used interchangeably.

** The Satipatthana Sutta from the Majjhima Nikaya, translated from the Pali by Thich Nhat Hanh and Annabel Laity.

*** MBSR stands for Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction, a tool often used in psychotherapy.

References

Thich Nhat Hanh. 1990. Transformation and Healing. Parallax Press: Berkeley

Kabat-Zinn, Jon. 2009. Full Catastrophe Living. Delta Press: New York

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Shining a Compassionate Light on Violent Communication

Rethinking Death with Natural Burial Practices

A Buddhist Perspective on Crime, Punishment, and Redemption

Acknowledging Mistakes and Moving Forward

The Light in the Darkness: Opening our Hearts to Hope

Related news from Buddhistdoor Global

Candle Blamed for Lunar New Year Blaze at Buddhist Temple in Southern California

HH the Karmapa Opens Dialogue on Human Emotions with Psychology Students